Sunday 6 October 2024

What the TPLF's early 2000s dispute reveals about the party today

The TPLF has a long history of factionalism and internal disputes. The recent issues surrounding the Pretoria agreement, which ended the two-year war in Tigray, are best understood in relation to the dispute that fractured the party in the early 2000s.

In late 2000, shortly after completing my studies at Addis Ababa University, I travelled to Mekelle, Tigray, to begin my first professional job. It was not an ideal time to be in Tigray. The border war between Eritrea and Ethiopia had just ended, and the ramifications of the conflict—still affecting Tigray today—particularly the split within the TPLF, had created a tense political climate. Tigray, as a region bordering Eritrea and the main battleground, was reeling from a devastating war that claimed tens of thousands of lives, caused immense economic damage, and displaced thousands. Various factors were cited for the split within the TPLF in the immediate aftermath of the war, but it largely centred on the conduct of the conflict, especially Meles Zenawi’s decision to cease hostilities rather than continuing to remove Eritrea’s Isaias Afwerki from power.

Subsequently, Tigray became a battleground for the intense internal power struggle between the TPLF factions—one based in Addis Ababa and the other in Mekelle. The acrimony and intransigence eventually ended when Meles’s faction triumphed by sidelining party stalwarts and veterans who opposed him and replacing them with more pliable members on the TPLF’s central committee. Writing about the struggle two years later, Medhane Tadesse and John Young said: “Ideological concerns and struggles for power merged in ways that can still not be completely understood, but it can be said with confidence that the result is a shift in power from Tigray to the central government in Addis Ababa, from the instruments of the party to the state, and from a group among the TPLF Central Committee to Meles Zenawi.”

Fast forward two decades, and the TPLF is splitting once again. Two factions, one led by Getachew Reda and the other by Debretsion Gebremichael, both based in Tigray but with alleged alliances in Addis Ababa and Asmara respectively, have been in conflict for months over a range of issues. Reda played down the dispute in an interview with Tigrai TV, describing it as a “power struggle that has gone awry”, but like the disputes old, he added that “that splinter group wants to portray itself as the repositories of the true sense of the TPLF.”

In a strange twist of events, aside from the involvement of new actors and the explosive impact of social media, the current turmoil bears an uncanny resemblance to earlier divisions. This split follows the two-year war between the TPLF and the federal government, described as the “deadliest of the 21st century”, which has claimed more than 600,000 lives and left the region in the grip of a colossal humanitarian crisis. The contentious issue between the two factions this time is not Eritrea but Ethiopia, particularly the signing of the cessation of hostility agreement in November 2022 in Pretoria, South Africa.

Founded as part of the Ethiopian student movement in the 1970s at Haile Selassie University, the TPLF has experienced periodic episodes of internal divisions and crises, including major conflicts in 1975, 1977–78, 1989, 2000, and now in 2024. These crises follow a distinct pattern in terms of beginnings, processes, and resolutions: they arise in response to significant internal or external events, followed by the emergence of opposing factions and chaotic phases of divergent responses, eventually leading to the dominant faction sidelining and removing the leaders and supporters of the losing faction. The party then reconstitutes itself, embracing the aims of the new leadership.

Following the signing of the Pretoria Agreement, few had expected the current internal division among the TPLF. There were telltale signs of division when the TPLF leaders were locked for months before selecting Getachew Reda as the leader of the interim regional administration (TIRA) with 18 out of 41 members of the central committee voting for him. This is a new political territory for the TPLF where the leader of the party is not the leader of a government, and a major departure from the TPLF’s modus operandi where the state, party and government have existed as fused or interchangeable institutions.

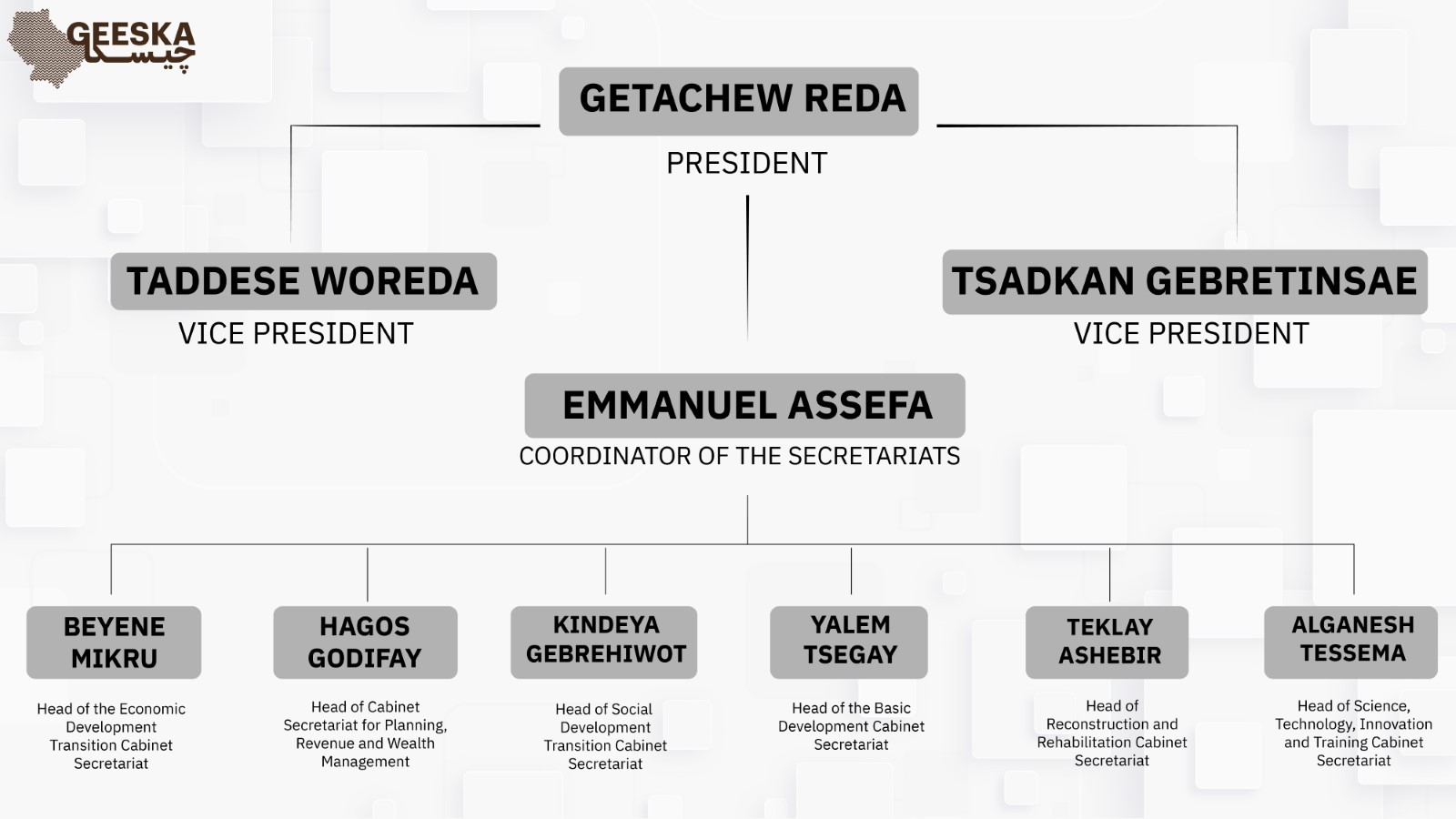

The TIRA, composed of 27 cabinet members and secretariats (16 from the TPLF, 4 from the TDF, 2 from opposition parties, and 5 from the GSTS), was established as a transitional entity tasked with prioritising and facilitating the restoration of Tigray’s territorial integrity, justice and accountability, and the return of internally displaced persons. However, developments since the establishment of the TIRA in March 2023 indicate that these priorities have taken a backseat. Instead, new agendas, such as the details surrounding the signing of the Pretoria agreement, reforms, and the mandate and authority of the TIRA vis-à-vis the party, have come to dominate the divisions between the two major factions.

*Tigray Regional Interim Administration as of September 2024

These divisions have not been confined to the leadership. Social media has amplified them, making them central to the current social and political discourse in Tigray, eliciting highly polarised views on partisanship, factionalism, and regionalism among ordinary Tigrayans. For many Tigrayans, the fact that leaders are focused on such power struggles at a time when the region is enduring a major humanitarian crisis has been a significant source of frustration, as well as a humiliating experience in the face of the current crisis.

But why is history repeating itself? Why does the TPLF find itself in a new cycle of political deadlock, dragging the region further into a political quagmire? And most importantly, how can Tigrayans emerge from the current crisis? The answers to these questions lie in understanding key events in the origins and history of the TPLF, the evolution of the party as an institution, and the leadership culture it has developed over the course of five decades.

To be clear, discussing the TPLF is no easy task, partly due to its outsized influence on the politics of Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa, and partly because of the contested nature of any scholarly discussion surrounding the historiography of the region. As with many contemporary or historical events in Ethiopia, the story of the TPLF suffers from what Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie calls “the danger of a single story”. To its supporters, the TPLF represents freedom, resistance, and resilience; despite its serious failings and miscalculations, it continues to enjoy a near-cult status. To its detractors, the TPLF is a bogeyman, embodying all the past and present evils that have engulfed the country, with many wishing for its disappearance from the political landscape of Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa.

However, the reality is murky and complex and cannot be reduced to a single narrative. These polarised views—whether originating from within Tigray or from outside and rooted in divergent ideologies and interpretations of the past and present—should not be used to gloss over the complexity or obscure the truth. Rather, they must be transcended to recover the insights critical to understanding the current crisis.

No rivals allowed in Tigray

The TPLF was established in 1975 with the specific aim of waging an armed struggle to liberate the people of Tigray from what it characterised as “national oppression and feudo-imperialist exploitation”, which it defined as the political, cultural, and economic subjugation imposed by successive Ethiopian governments. At the time, Tigray was also home to other rebel groups, including the Tigray Liberation Front (TLF), Ethiopian Democratic Union (EDU), and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Army (EPRA), all vying for influence and support among the Tigrayan population. The TPLF, one of several rebel groups with divergent and often conflicting political programmes, emerged victorious after defeating these factions, eventually expelling the TLF, EDU, and EPRA from Tigray by 1980.

These early struggles for supremacy were defining events during the TPLF’s formative years, shaping the party’s modus operandi towards alternative ideas and organisations, and prefiguring its relationship with and response to opposition parties at both regional and federal levels. When it assumed power in 1991, the TPLF carried forward its legacy of dominance from the armed struggle era into governance, continuing to suppress the emergence of meaningful opposition in Tigray. This historical context is crucial for understanding the current political turmoil, as well as the party’s aversion to new ideas and its rigidity in adapting to changing realities.

Does vanguard leadership need to give way?

Alongside its struggle for dominance in the Tigrayan political landscape, the TPLF was also seeking viable leadership and organisational frameworks to secure its institutional existence and address the pressing issues faced by the people in the areas of Tigray it had liberated. The founders of the TPLF, well-versed in the Marxist-Leninist ideologies of the time, chose to adopt the concept of a vanguard party, as conceptualised by Mao and Stalin, which they found useful in meeting their leadership challenges.

Consequently, they established a governance model that involved “consultation of the communities in framing problems and identifying solutions, while decision-making authority remained within the vanguard organisation and its structures”.

Leadership scholars have examined the distinctive features of vanguard leadership and its effects on leaders and followers, identifying characteristics important for understanding political parties like the TPLF. Dennis Tourish, an expert on leadership and organisations, explains that the notion of a vanguard party predisposes leaders to view themselves as the “pivot on which world history is destined to turn”, instilling them with the belief that they possess unmatched insight into society’s problems and are therefore indispensable. Central to the practice of the vanguard party is the concept of democratic centralism, where power is concentrated in the hands of a small, highly influential group, and where strict hierarchical obedience is enforced, with dissent regarded as counter-revolutionary and suppressed.

The vanguard leadership embodied by the TPLF's early leaders enabled the party to stay closely connected with the population and implement far-reaching, progressive policies such as land reform, devolved local councils, and educational and socio-economic programmes aimed at the emancipation of women. It also positioned the TPLF as the sole custodian of interpreting collective experiences, distilling them into policy formulation and strategic decision-making. This cemented the TPLF’s status as the most significant and hegemonic actor in Tigrayan society, dominating social, political, economic, and cultural arenas. Such monopolistic leadership was effective during times of war, when the party needed discipline and organisation while simultaneously engaged in both armed struggle and the governance of liberated areas, where it operated as the only authority without a contender.

However, in peacetime, when the party assumed power in 1991 and became a government, the distance between the leaders and the people grew. As leaders became less responsive to the grievances of ordinary citizens, this leadership model lost its effectiveness and evolved into a tool for suppressing dissent and democracy, rather than serving the needs of the people.

These characteristics of the TPLF—its dominance and vanguard leadership—have left a lasting impact on the politics of Tigray and provide important context for the current political crisis. The (un)intended consequences include an aversion to alternative political ideas and organisations, a rigid and hierarchical leadership culture, and a political environment in which dissent and disagreements result in zero-sum outcomes. For Tigrayans to emerge from the current quagmire, while recognising the role of external actors, they must focus on the structural aspects of the crisis rather than personal ones. This requires confronting the dominant political force and its modus operandi, salvaging what is valuable, and discarding the rest.