Tuesday 19 November 2024

Hip-hop and revolution in Sudan

“The State is afraid of the Pen, While we’re here challenging death”

-Flippter

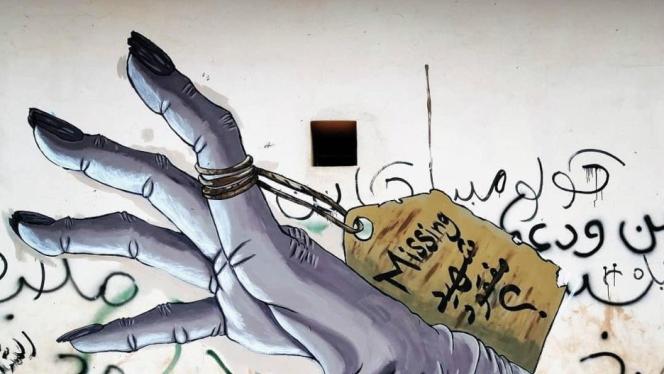

The streets of Khartoum in December 2018 were not just crowded—they were buzzing with life. Voices rang out in defiance, marking the end of three decades under Omar al-Bashir’s authoritarian grip. It was a revolution, but it was also a revelry of the spirit. A hidden energy, repressed too long, spilled onto the streets, transmuting protest into art. The sound of resistance in Sudan was not a single note but an orchestra of beats, rhymes, and chants—and the sound of Sudanese hip-hop. Hip-hop had simmered underground for years, but now, it had erupted into a national chorus, becoming a vehicle for the expression of the hopes, grievances, and dreams of Sudan’s youth.

Ayman Mao was among the first to carry the torch. His track “Dam” (“Blood”) from 2016 had already gained traction; a gritty and furious indictment against the powers that exploited the people. How much did they buy you for, so that you can turn it into blood?

Mao’s words resonated with thousands, transforming his lyrics into rallying cries for those now gathered in protest. This was not just a song but a haunting reminder that their blood had been shed during their resistance against the Bashir regime. As his lyrics bounced from building to building, they fused with the chants of the crowd, a single voice shouting enough.

Mao’s impact was only the beginning. Flippter, a Sudanese rapper who had long explored themes of alienation and struggle, joined the front lines with his track Hatred. “Might get a bullet for these simple words,” he rapped, fully aware of the risks. In his track Blue, he described a homeland that felt foreign, echoing the sense of displacement that Sudanese youth felt under a regime that cared little for their voices. With each verse, Flippter not only exposed his anger but also his refusal to be silenced, a poet who embraced the pen as a weapon. Sudan’s youth found something vital in Flippter’s words—an unflinching mirror reflecting both their frustration and their resolve.

Diaspora voices joined in, with artists like AKA Keyz, who, from afar, could still feel the pulse of the homeland. His track “No Options Left” became an anthem of its own, a bleak yet determined reflection of the state of Sudan. No potions left, he repeated, voicing the despair and hopelessness that Sudanese youth felt as they watched their nation unravel.

These modern voices were joined by icons from the past, blending tradition with rebellion. A.G. Nimeri’s “Sudan Without Keizan” echoed across the revolution, a song imagining a Sudan freed from the grip of corruption, racism, and religious manipulation. Sudan without merchants of hell and heaven, he sang, condemning those who used religion to justify violence and control. Nimeri’s music bridged generations, evoking a Sudan that existed before Bashir’s rule while dreaming of a future without it. His song, like so many others, became a soundtrack for revolution, articulating the shared yearning for a new Sudan.

The roots of Sudanese hip-hop stretch back further than the 2018 protests.

In the 1990s, American rap tapes circulated as bootlegs, slipping past government censors and sparking the imaginations of young Sudanese. By the 2000s, artists like the group NasJota had fused hip-hop with traditional Sudanese sounds, blending Arabic and English lyrics to create something distinctly Sudanese. Their success was short-lived, however, as government censors quickly silenced their socially conscious lyrics. Artists like Mao were forced into exile, but the spirit of protest they had ignited continued underground, shaping a generation of young people who saw music as a form of rebellion. By 2018, Sudanese hip-hop had made such an impact that GQ produced a list of almost 20 rappers that it wanted its readers to know about including Bas and Omar Majid.

In 2019, as the protests reached their peak, Sudanese hip-hop transformed from an underground movement to the heartbeat of the uprising. Mao’s “Dam” and Ali G’s “Taskut Bas” (Just Fall) blared from speakers in protest camps, the lyrics striking raw nerves as they condemned corruption, repression, and violence. But hip-hop was not just the backdrop; it was the movement itself, a thread weaving together thousands of voices in a shared demand for freedom.

Then, in 2023, hope turned to tragedy as violence erupted once again. The simmering tensions between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces ignited into civil war, and the country was engulfed in chaos. Artists found themselves displaced, with some forced to flee. But even as studios lay abandoned and streets emptied, the music continued. Hip-hop artists in exile, in Egypt and across the diaspora, kept creating, their voices reaching back home and keeping the spirit of the revolution alive.

New platforms like Rapshar3 (Streetrap) became vital spaces for Sudanese rappers in exile, where artists poured their anguish into verse. Hyper’s song, echoing Sayid Khalifa’s iconic chorus, reflects on those days of revolution with both nostalgia and bitterness. Those were days, O’ country, days like the dream, he sings, mourning what could have been, even as he curses those who have ruined those dreams.

And new voices emerged—Veto, Awab, Ghayaz—documenting in verse the personal toll of war. My brother was shot dead but is not buried yet, Veto raps, his words an indictment of those in power. It’s a painful, raw reminder that for many Sudanese, freedom remains distant, as if glimpsed only briefly before being snatched away again. These songs became not just records of protest but oral histories, documenting the suffering of a people in real time.

Sudanese hip-hop has emerged not only as a form of rebellion but also as a repository of the nation’s collective memory. What began as borrowed beats from American rap tapes has evolved into a genre that is uniquely Sudanese, defined by the local language, the rhythms of traditional folk music, and the cadences of Sudanese Arabic. The genre has forged its own identity, producing a sound that resonates deeply with listeners across Africa.

Now, as Sudan stands at a crossroads, the role of hip-hop has never been more critical. These artists—both those at home and those in exile—continue to create, documenting their stories and struggles. In doing so, they ensure that even as the country spirals, the voices of Sudan’s youth will not be forgotten.