Tuesday 19 November 2024

Ahmed Ismail Samatar interviews Nuruddin Farah

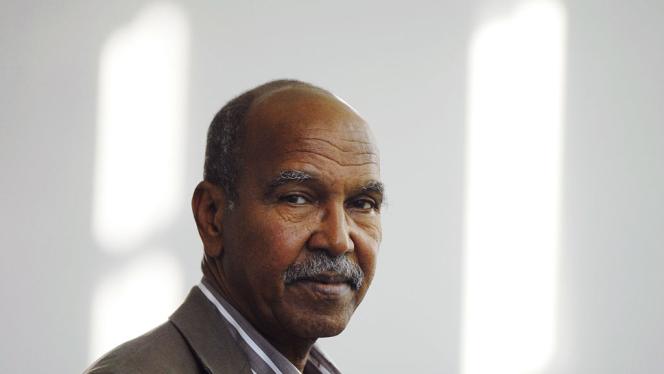

Neither Nuruddin Farah nor Ahmed Ismail Samatar requires an introduction for Somali readers. Farah, a novelist, and Samatar, an academic-turned-politician, are two of the most incisive interpreters of the Somali odyssey through the postcolonial era. Farah, to borrow an expression from James Baldwin, is as an “emotional or spiritual historian” of the Somali experience, while Samatar combines a literary sensibility with is scholarly background to provide fresh and fascinating insights for people interested in current Somali affairs and Somali history. Both are authors of multiple books and are prolific writers.

In 2008, Ahmed Ismail Samatar conducted an interview with Nuruddin Farah, which was published in the Bildhaan journal. Their discussion was wide-ranging, covering Farah’s literary biography and early influences, his reflections on Somalia’s stateless period post-1990, his own regrets, and the failure of Somali intellectuals, the religious class, and clanist politicians to steer the nation out of its current morass.

This exchange is a conversation between two of the most fascinating and original Somali thinkers, on all the subjects Somali thinkers have obsessed over since 1990.

Ahmed Ismail Samatar: Let us start at the beginning. Tell us how you happened to become a writer? What inspired you to write?

Nuruddin Farah: Well, I don’t know if I decided to become a writer. I will respond in terms of my life. I think what happened is that very many different circumstances which were working in tandem made it possible for me, eventually, to become a writer. But this is many, many years after I started to write. And I remember quite clearly that there were three or four things that made me start to want to write. One of them was that every time I read something in any language, and at the time I was growing up in the Ogaden region and under Ethiopian domination, it introduced me to a whole lot of characters and ideas, and I discovered, for example when I read Crime and Punishment by Dostoeyevsky in Arabic, when I read Les Misérables, also in Arabic, or books in English, that there were no Somalis in those books, nor did I find Somalis in 1001 Nights, or in any of those stories. Now, the reason why I was looking for Somalis was so that I would be able to say, “this is something I know, this is something that is not alien.”

The closest I got to finding someone with my own name was in 1001 Nights: there is a prince called Nuruddin, about whom there is a story. So one of the first things that I started to do was to cut out the name Nuruddin from all of my copies of 1001 Nights (and God knows how many copies I destroyed), add Farah, and then put them on my exercise books, and say “Look, I’m a writer, I’m a writer.” This is how it began, more or less like a child’s joke. However, later, I discover that in our English language textbook there was a story about animals, about rats and cats, and how they spoke and engaged in some conversation. And so, apart from writing my name on the exercise books, I changed the names of the characters, the animals, associating the good parts with the people I liked and giving the bad lines to those I did not. The third concerns my mother who used to compose buraanbur. She would occasionally ask me to deliver a message in the shape of a buraanbur to the reciter, the preacher, or the person who was to preside at a wedding or at an important occasion. Because she had been busy with the ten children, she would “talk” the composition to me because I was very good at remembering and memorizing. She would speak to me only once or twice and then I would deliver it the way you would deliver a letter to someone else and say, “My mother asked me to deliver this message.” She would be given the background or the history of the people who were getting married or the occasion that was being celebrated and then she would compose a fitting buraanbur.

In return, I would bring back sometimes food, sometimes a gift, some small message sent in kind. The fourth thing, and this is also very important, is that I was one of the few children of my age (teens) who knew how to read and write Arabic, English, and Amharic. Such a capability made it possible for me to offer my services as a letter writer to people who were illiterate and much older. I remember specifically how one would compose the letter and, at the end of it, sign one’s name. I got involved in one memorable incident, which concerned a man who was brutal with his wife. He used to beat her up frequently and would constantly threaten her with divorce if she did not obey his commands. This man happened to be a friend of my father. One day, he asked me to write a letter to his wife. He spoke of beating her up again “until she came to her senses.” I was appalled by this and decided to change the text. It read like this: “Since you are not listening to me, I divorce you.” Now, the man had no idea what had happened. Because I had written my name at the bottom of the letter, word came back that the man was looking for my father. When they met, he said to my father, “Your son has created a situation in which my wife is now divorced from me and is married to somebody else.” I was savagely punished by my father and ordered never ever to do that again.

AIS: How many languages do you work with? English and Somali, of course, but any others?

NF: I don’t anymore use other languages as much as I used to when I was younger because I am more inclined to play with ideas. For example, I even started writing bits in Italian or Arabic. I did write in Somali. I did write a novel in Somali and a number of chapters were serialized in Xidigta Oktober (The October Star). The installments ran for several months. This was 1973, barely a year after Somali became a language in the script. Unfortunately, the publication of my novel was discontinued because of a censorship regime that was enacted soon afterwards. So my idea at the time, because I was also living in Somalia, was to resume my interest in writing in Somali. It never came to be because I left Somalia and never returned.

AIS: I would assume that besides Somali and English, you still think in other languages such as Arabic...?

NF: Arabic, and Italian, and I read French, and I read a little German, not much, and then I also have an attachment to the literatures of India because I went to university there. I am interested in literatures being produced in other various parts of Africa, where I have traveled and lived in a number of countries.

AIS: Could you tell us about the individuals or an individual who has had the greatest influence on you in your development? Why do you think so?

NF: Three persons stand out. The first was my mother. I used to watch her as she composed her buraanbur. Her technique was fascinating. She would pace back and forth in the room and think about the subject, compose it, speak it to herself. From this experience I learned that the creation of a text was a process that required time, thinking, ingenuity, and self-trust. The second person would be a man called Adam Jama Bihi, who was helpful materially as well as intellectually. He was a bit older and more worldly than I was; he had just come back from England. He was one of the first persons to give me encouragement and to say, “You can do it,” when I didn’t have the confidence in myself as a nineteen-year-old. When I wrote something, he would read it and comment on it. So Adam Jama Bihi was the first person who read some of the first texts that I had ever written. Then there was another man from Hargeisa, called Ismail Booba, who, by example, helped me because he was the first Somali writer I had met who had written something and published it. It was a short story. I don’t think I understood it. But I was impressed with the mere idea of being published. You know this was so earthshaking given the oral tradition of Somali society. Booba’s story had the title of “You and I”, and it was part of his master’s project in creative writing in the United States.

AIS: What about non-Somalis? Any great historical figure in the writing world — novelist — that you continue to find inspiring, perhaps a model?

NF: There are writers who’ve influenced not only myself, but have shaped the whole century. Two of them happen to be Irish. One is James Joyce; the other is Samuel Beckett. And then there’s the American, William Faulkner. Now, these are writers who influenced me in a major way. There are other writers from whom I picked up a couple of ideas. But those three are the ones who one tries to emulate. A major writer is one who has a greater vision than she or he is capable of capturing immediately. And you know, you go for broke, you do everything that you could, and these are some of the writers who’ve done tremendous things. Later on, of course, I encountered Achebe.

AIS: Achebe would be one of the more early ones?

NF: Achebe would be one of the few. His work impressed me immediately. While I am no longer as dazzled, I continue to hold Achebe in high esteem and the reason is because he has been steadfast in his philosophy and Africanness.

AIS: Could you comment on an event, if there is one, that has had a most lasting effect on your own work and continues to come back again and again in your own memory and your own experience?

NF: The event that determined the direction of my work is one that took place in Rome in 1976, in the month of July. I was preparing to go back to Mogadishu, after two years of graduate studies in theatre. I picked up the phone and called my oldest brother to collect me upon arrival. Earlier, I had published Naked Needle in Britain to good reviews. I am not in the habit of reading the reviews of my works, but, apparently, word about the novel had reached Mogadishu. My brother was quick and clear. He told me to “forget about Somalia.” He relayed how the Somali ambassador to London had sent photocopies of the reviews to the leadership in Mogadishu. The novel was described as satirical and the author as cynical toward the regime of Siyaad Barre. In short, between one day and the next, I was a traveler when I arrived in Rome but became an exile after that telephone call. It is a very concentrated moment in my life. Moreover, it is very difficult to overestimate its pain and meaning, especially when you are relatively young and with no money or other immediate options.

AIS: Perhaps we could talk a bit about what lies behind events. Do you have deep moral attachments or core values or inherent curiosities that are a foundation for your imagination as it takes a variety of trajectories and directions?

NF: I have. My basic sentiment is the very one that I started with ages and ages ago, which is to find Somalia in books. I am not saying that the things that I write are sufficiently more Somali than those others have done. We will leave this for posterity to judge. However, my great mission in life became one of keeping Somalia alive by continuing to write about it; by turning it into a debate; by making Somalia intelligible to others, including Somalis. With fellow Somalis, my mission has always been to go beyond the superficial, beyond what everyone knows and into the hidden secrets, into taboos and things that are unsaid because people are afraid to do so. As a novelist, I usually think of myself as somebody who imagines that there are no secrets worth keeping, no taboo areas in human life. So, for example, in a novel such as Secrets, erotic moments, not pornographic, are described (and it is difficult to explain to someone who does not understand the differences). One should be shocked by what Somalis have actually done to each other and their denial of such acts and less by descriptions of lovemaking between a woman and a man created by the imagination. In the end, as a novelist, I am interested in every aspect of human activity.

AIS: You started your response to this question with an emphasis that you want to see Somali society, its culture, and its history, and other attributes written and talked about, published in books. Why do you care about Somalia, especially given the experience of the last 25 – 30 years?

NF: Because not many other people care. This is my belief. Because I am one of the few Somalis who has continued to travel with a Somali passport, and one of the few Somalis who has held to the belief in Somalia, not in a family, not in a clan, not in anything else, but in the sanctity of the notion of Somalia. And, of course, the Somali people as a whole. It does not matter to me if someone comes to me and says, “I am your cousin.” I would say to him, “You are just as much a Somali to me as anyone else” In other words, because I have lived in exile for many years, and know of three assassination attempts on my life, I kept asking myself this question: what is worth being killed for? You see, why would someone take it upon himself, sort of self-sent, to eliminate me? If what I was doing made someone want to assassinate me, then it must have been worth doing. This is one way of looking at it.

Another way is that the Somali mess is the very thing that most people fled; they don’t want anything to do with it. And the reason is because Somalia is a bad image, it’s not worth selling, it’s no longer worth associating with, and Somalis that I know, and I can name a couple today, when they’re asked where they come from, they say Ethiopia or Sudan. Even though they live in the United States, even though some of them may even be professors, even though they have American passports, the mention or association with that terrible thing called Somalia shocks them. Well, I take great pleasure in telling people I am a Somali. As I identify myself, I actually also explain what has happened in ways that can be understood by other people in other places because what happened in Somalia could have been foretold, and some of us did. I am, therefore, proud of not only being Somali but also continuing to carry the badge. The one thing that disturbs me, keeps me awake, gives me nightmares, is this falsehood we tell ourselves all the time: denying that we had anything to do with it; denying, for instance, that somebody who was a prime minister of the country for years, together with Siyaad Barre, had no involvement, or a minister of education declaring a little later, “No, I had nothing to do with it.” I, who have never worked for the state of Somalia, except as a small, lowly typist earlier in my life and a few years of teaching at the university, am willing to say that I, too, am an accomplice in the ruin of Somalia.

AIS: We’ll come back to the Somali saga, but I want to stay a bit longer with your own works. Of all the novels that you have written, which is the one that you, at this particular time in your life, think is the most significant, your favorite?

NF: I think it is Close Sesame.

AIS: Why?

NF: Well, first of all, it is a book whose characters are very dissimilar to me. It’s a work that is very sane, calm, religious, well proportioned. It talks about Somalia of more than one century. It’s a book that actually deals with violence, and whether or not it is Islamic to engage in violent action — if it is justifiable to kill someone for political reasons. I wrote it in 1982. It was published in 1983, and, therefore, it is the one book that will probably stay for much longer than many of the other books. I’ve discovered that each of my books has made its own friends. But I think that’s the one book that will probably endure.

AIS: What about writing in English? Does this present a special challenge? And if so, how do you deal with it?

NF: I don’t think it’s a challenging activity because of the language.... I think writing, sui generis, is the challenge. I sit in front of my computer and it is as if I have never written anything in my entire life. Everyday is a new process of relearning. Would it have been easier if I had been writing in Somali? I doubt it very much, because writing in general requires discipline and extensive research into the area about which one is writing. Now, whether I conceived these works in Somali or in English, I will still remain the same person, and the ideas that informed my writing would have been the same. Let us take the example of From the Crooked Rib. This was about society and dictatorship, a society that says to a given segment, that is the female gender, that they are not equal to the male and should not be treated as such. Now, I worked out at age 22 or 23 that there was injustice in the way things worked in that society. With the rise of the political dictatorship of Siyaad Barre, it was easier to follow up on a mystery I had already cracked open. While many other people still found it perplexing how Somali society treated women, for me it was and continues to be an invitation to dig deeper into the constitution of Somali culture.

AIS: Comment briefly on the relationship between language and the native imagination. If one can say that your native imagination certainly grew in Somali culture and language and symbols, then the shift from that context to another culture and language seems formidable. How hard is it for you to move back and forth between the native imagination of Somali to English, a medium embedded in a different kind of a historical experience and civilization, or is that not a problem for you?

NF: No, no. I’ll tell you why it isn’t. First, maybe because I was young and, therefore, any problem was just a challenge to be overcome. Second, even if I were writing From a Crooked Rib in Somali, the composing of the story, the sequence of the narrative, the putting together of the story will pose comparable difficulties. The language is not the main issue; rather the key is, in the end, the ideas that carry the book. Now if you ask people what they remember of From a Crooked Rib, they probably will recall the story, how it was told, and the way the reader was carried to enter that world. In the final analysis, much depends on the core ideas.

AIS: Let’s talk a little bit about exile, and the contradictions of exile. For some, not just Somalis, exile can be a gateway to a whole new freedom and a sense of opportunity to shed the liabilities of one’s own heritage. However, for others, the experience can be tantamount to the drying up of the self. What does exile mean for you?

NF: Let me start with my own reaction to going away from home at first. As a young boy, I was sent to school in Ethiopia, away from home. On my first return, I discovered that I was bursting with stories I wanted to tell people. However, the second time, I didn’t want to share because I realized that many of the things that I saw could not be explained to people who have never seen it. What can you tell to these people who have never been to a city, and who are in a small district town? It’s the same. What happens is that there are many, many things that you cannot explain to the person who has not experienced it. Now, I’ve turned this into a positive force. I found energy in discovering Somalia outside Somalia, whereas many Somalis discovered or lost Somalia in Somalia. For me, exile has been an attempt at squaring the circle insofar as Somalia is concerned. I keep asking the deep questions: “What is Somalia? Who is Somali? What does the country mean? Why is it special? What has gone wrong with it? What can one do about it?” So what exile has done for me is that it has somehow freed me from the family constraints, and, particularly in terms of Somalia, family means my father sending me a message and saying, “Nuruddin, you’re a small boy, but this is a big man’s world.”

AIS: In the interpretation of your critics, some of your recent works, especially Secrets, use concepts or themes that border on the pornographic when presenting illicit sex scenes. Who is your audience, particularly for a novel like Secrets?

NF: There are many questions here so let me say, first of all, that I don’t actually have any audience in mind when I write a novel. I write and I am the first audience. Anyone else who has the time to read them or who is able to read them, that’s fine by me. Normally, what I do in my fiction is to write what is known as a literary complex novel. And then, usually, such a novel is followed by another that’s not very complex. So that if you took, for example, at the trilogy Maps, Gifts, and Secrets, you will find that Maps is a complicated sort of novel, and that you are required to do a lot of literary and psychological analyses to appreciate it. This is followed by Gifts, which is easier to read. Secrets is much more complicated, in literary terms. Nonetheless, an attentive reader may gain some insights into Somali society. Let me now come to the question of whether this novel is on pornography or not. First of all, I will not use the word “pornography.”

If I were to pick a term, it will be erotic, and there is a literature of the erotic. There is a very big difference between erotic literature and pornographic literature. In pornographic literature, sex itself is the means and the end, whereas the erotic novel has other objectives but may contain scenes that are erotic. Now, anyone who knows or is conversant with literature would be able to quote to you a great many, some of the most celebrated novels in the twentieth century, that would have a chapter or two chapters similar to one or two of the chapters in Secrets. For instance, read Ulysses by James Joyce. One of the chapters in Secrets was inspired by one of the chapters in Ulysses. There is, however, a need to mention that one of the reasons why sex, incest — both forms of illicit behavior—were looked at from different angles is because the basis of the story of Secrets is about paternity, and, therefore, illicit sex may produce a child. Non-illicit sex may not, and, remember, this is a woman who is trying to have a baby. The man is not willing to accommodate her. How is one to solve such a narrative impasse? This is the question that I asked.

AIS: Gender and the condition of women are two conspicuous elements in almost all of your works. Why is that so? Is there any intended message to Somali women readers?

NF: I’ve always thought that society could not be considered free, democratic, developed, let alone “civilized,” when a large segment is kept out of the mainstream of politics and life. It has always been my belief, as well as that of many, many other Somali poets, writers, and thinkers, that women ought to be given a central position in the life of the nation. And I would like to say that, although I started writing about women early on in my life, more recent events in Somalia have vindicated the positions that I have always taken, which is that the leadership of Somalia ought to be placed in the hands of women and sympathizers to the causes of women in view of the fact we—the male society—have failed. Secondly, because women fall between clan families (that is, they could be married to one and have the children of different clan and family origins), women seem to me to be a symbol of Somalia insofar as they are also an oppressed segment of our society.

The current situation seems to underscore that women have proven to be far hardier than men. Whereas men have broken, have collapsed, have begun to mourn what has happened to them, put their heads between their hands, not knowing what to do, women have gathered their forces and have helped their immediate families. Many, many men waste their time uselessly eating qat, whereas their women counterparts, in Italy, in Canada, in the United States, in England, have taken upon themselves social responsibilities that many men do not seem to seek. While men chat all the time about cheap politics, women are busy raising their children as well as the consciousness of Somali society. In my own immediate family, I would say that all my sisters are doing very well in spite of the catastrophe but almost all my brothers are not. I have a feeling that this is true for a great many Somali families.

AIS: What are you currently reading?

NF: I’ve just, in fact, finished a memoir by an Ethiopian, a young Ethiopian writer. It’s his first book. He lives in Canada now. I suppose he’s Canadian-Ethiopian. And the book interests me because it is set in Jigjiga. The young writer talks about his experiences of growing up in Jigjiga, and of joining the Somali Liberation Front to fight against the Derg. Later on, as is to be expected, he is excluded from taking any important position or occupying a strategic appointment in the movement. I find it a moving novel, not that I agree with many of the things he says about Somalis in general, or non-Somalis, because he doesn’t speak the language very well, which is a great pity because you would think that someone who grew up in Jigjiga would be able to speak the language. But he is cognizant of those shortcomings. Another book I am reading is by a South African, and it is called Dream Birds. It is about ostriches and how trade in their feathers at the turn of the eighteenth century and early on in the nineteenth century proved to be very lucrative. I recently read a book Paul Gilroy called Against Race. So, I’m reading different books. Sometimes I read fiction, and I’m now about to begin J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace.

AIS: Quite a spread! Could you tell us a little about your work in Progress?

NF: I’m working on a novel set in Mogadishu between 1991 and 1994; a novel set in the period when the Ali Mahdi and Aideed groups decided on taking Somalia to total ruin, which they did eventually and also the presence of the UN and US forces. So, I’m reading as many different books as I can, talking to as many people as I can. This novel is about two-thirds done. I should also like to mention that a new book has just come out, nonfiction this time, about Somali refugees and exiles — Somalis in the diaspora. The book is called Yesterday, Tomorrow: Voices from the Somali Diaspora, and it is published by Continuum in New York and London, and it should be interesting, I suppose, insofar as all Somalis are either refugees or exiles. It is about that condition — the collapse of Mogadishu and how it all started, and how the violence came to be different. How Somalis became defined by the violence…

AIS: You move between fiction writing, the novels, and then essays, much like this new volume that is a series of essays and observations that you have conducted. What kind of technical intricacies and labor goes into shifting between these two different genres of production?

NF: At any given time, I would be working on a minimum of three things. They may be a short piece for a newspaper, a longer piece for a magazine or literary journal, a book (a novel), and then sometimes a short story as well. They are, actually, not the same in one way, and yet they are. Basically, every morning, when I get to my work table, I feel as if I have never written anything before, and every morning there is a new process that I go through and different ways of getting myself acquainted with the thing on which I am working. Ideally, I would like to work from about 8:00 in the morning until 4:00 in the afternoon, with probably one hour break in between.

So, there are too many hours of work, which are divided into reading time, reflection time, and writing time, or revising time. Revising, indeed, takes a lot of time. The big difference, I suppose, between the nonfiction and my novels is that on the nonfiction I like to do a great deal of research, and lots more research than I do for my novels, because even for my novels I do some research. For Yesterday, Tomorrow: Voices from the Diaspora, I’ve had to go to Kenya to interview Somalis as they were fleeing Mogadishu and the beginning of the Somali civil war.

So this is a book that actually started in 1992, and then went through Ethiopia where I lived for a year, to check the temperature of the Somalis present in Ethiopia. And then I went from there to dig into the history of Somali presence in England and in Italy, two former colonial powers in Somalia; and then two non-colonial powers, such as Sweden and Switzerland, where I also interviewed Somalis; and Somalis from Canada, and so forth. So a lot of research went into this, and much of the book, its main body, is actually interviews that I conducted with Somalis. The reason why the book took a long time is because, first of all, I had to raise the funds. Secondly, because I had to translate some of the things that people said to me in Somali, and I had to find a way of representing them decently and in an elegant way. Sometimes you could make things sound very cheap or you could elevate the level of the dialogue and the conversation. Because I know the pain we Somalis have gone through, I have tried to elevate the level of the dialogue to a respectable position.

AIS: Do you read other Somalis who write in English?

NF: I do. I also read Somalis who write in Somali and Somalis who write in French, and I have read Somalis who’ve written in Arabic. I read basically anything on Somalia that I can get, all of it. In fact, what has been very helpful for Yesterday, Tomorrow is that I have been able to read books written in Italian by Somalis who were present when Mogadishu collapsed, and books written in Somali by somebody like Aw Jama Omar Ise, the historian, and many other different views of Somalia. I’ve also read a short book, only 38 pages long, by a most outstanding Somali. He was a witness when the Somali seamen rioted, many years ago, in Liverpool. This man was from Berbera, and he himself was a seaman. In short, I have respect for people who put down on paper the thoughts that cross their minds because then you have evidence of what they say and think; whereas those, like many of us Somalis who have a short temper and speak all the time — then it is very, very difficult to have a dialogue with them.

AIS: Any thoughts on the state of Somali intellectual culture?

NF: Well, I do not wish to be disrespectful to many of my friends and colleagues, but, and to begin with myself as a Somali privileged enough to be counted among the educated, we have failed in our responsibilities. Many so-called Somali intellectuals betray their own

nature and position by the Janus-faced politics in which they are engaged, and by becoming spokespersons for sectarian interests. Instead of being outsiders who objectively and judiciously comment on what is taking place, more and more Somalis have begun bearing the banners for one segment of Somali society or another. I could be wrong here and could be challenged on this, but this liability probably goes back to the political formations of the pre-Siyaad Barre era, so-called democratic regimes, and the Siyaad Barre time, as well. Somali intellectuals were seen to represent two sides of different coins. They were so-called intellectuals because they knew how to write their grandmothers’ names, whereas other people didn’t even know how to write their own, and, therefore, they were respected and always addressed as Dr. this and Dr. that. Also, they never played to the nature of clan politics in Somalia. Consequently, they lost the opportunity to capitalize on their kin affiliation.

Moreover, when the crisis —Siyaad Barre’s crisis—began many years ago, and I was living in Rome and traveling through London or the United States, and I met my colleagues, friends, intellectuals (so-called), I said, “When you write to Amnesty International or talk to the State Department or talk to the Ambassador, the U.S. Ambassador in Somalia or somewhere, please do not say ‘so and so, who is of this particular family, is in jail.’ Just say, ‘so and so, who is an opponent of the dictatorship of Siyaad Barre’s administration, is in prison.’” This is the way to avoid tactics of divide-and-rule, playing into the hands of the likes of Siyaad Barre. What he wants is his opponents not to be identified with an ideology. Barre always dealt with people in terms of families. I remember going to Amnesty International in London and speaking to someone called Martin Hill, and others.

I put my cards on the table, and I said to them to not mention the names of any of the kin families that these people came from. I told them that the reason why these people are in prison is not because they are from this family or that family, but because they oppose the tyranny. My position was the same when intellectuals would come to someone like me, and would ask, “why do you not write about this particular person who is from this particular family?” and I would say, “and I do write about families, I write about people with an ideology.” My own brothers—I can tell you quite openly—my own brothers and I, sometimes, if we sit in the same room for longer than ten or fifteen minutes, we are at loggerheads. Not because I don’t love them; I love them. They are my brothers and I know them well. But we can’t sit together and the reason is because of differences of ideology and politics.

AIS: That takes us, then, to the role of intellectuals in the contemporary Somali predicament. There are many in Somali society who expect from those who they see as “their” intellectuals, no matter how few, that they ought to lead in the remaking of Somali society. Given what you have just said, do you think that this is a valid expectation? Can Somali intellectuals become part and parcel of a new leadership dedicated to renewal and rebuilding of institutions and culture?

NF: I think they can, but there are conditions attached to this. One of them is honest rethinking, and the admission of the errors that they contributed to. The fact is that they are major actors and accomplices to the ruin of Somalia. But they are not alone in this. As I have said earlier, the entire Somali society is to blame. No Somali is innocent today, and no Somalis can claim that they have not contributed to the devastation of Somalia, including myself. There are two other groups with which I am also quite at odds.

First are the Wadaads, whom I respected. Because of the esteem in which they have been held, and because of their extraordinary knowledge and communication with various segments of society, I had assumed that many of them would occupy a leading position and show us the light. I expected that they would owe no allegiance to family X or family Y, but I am disappointed in them because many of them have failed to speak the truth. More recently, everywhere you go, you will find that most of the Wadaads advocate this or that form of religious rule in the new Somalia. In reality, they are not after the reconstruction of Somalia, they are after power. Now, I have another gripe. I suppose this is really the decade of gripes, and my gripe is also with the elders. I’m in my fifties. I’m one of the elders; not only that but I’m also one of the so-called intellectuals.

So I’m sharing this gripe in such a way that I do not exclude myself from it. I point toward them because the so-called warlords have relied so much on the elders of the so-called clan families, to whom they have gone and who have provided them fodder for their battles, for their battle wagons and their provisions. It’s my view that the elders are the ones who talk to the young people and say, “All right, we must protect this particular interest in terms of a territorial and financial interest.” They failed by collaborating with Siyaad Barre. They failed by collaborating with the warlords. They have all become sycophants or exploiters. Now, if you said to me, who, then, are going to lead in the reconstruction of Somalia, I would say to you that these three groups have nothing left in them. This, then, takes us back to the gender question. I would say that the only communities — larger communities — who have not taken so much blood, not shed so much blood from other communities, directly with their own hands, and have a clearer conscience, are Somali women.

AIS: The long dictatorship and the ensuing civil war that began in 1991 have created such a fragmentation that many people are proposing the creation of new and multiple sovereignties (e.g. Somaliland and Puntland) out of the ashes of the old Somali state. I am wondering whether you think this is a viable way to end the chaos and reconstitute Somali society?

NF: As you know, Mogadishu became the de facto state, and the reason was because everything was concentrated in Mogadishu. The government was in Mogadishu. The rest of the country was hollowed out, with little happening. So, I suppose you could say that the new sovereignties are creating new cities; in other words, new possibilities, new alternatives to a dictatorship, to the one in Mogadishu. But then I ask myself the question: Why should somebody continue accepting that Mogadishu is the capital of the country? Why could we not all move to Hargeisa? Why could we not move to Bosaso, somewhere more central where there is peace? If the idea of the alternative sovereignties is accepted, then we shouldn’t accept Mogadishu as the capital. I think I like the idea of there being alternatives, and the reason is because I’ve lived in Nigeria and I now live in South Africa, and the city of Cape Town functions independently from Pretoria, Johannesburg, and Durban and Bloemfontein, and so on. Consequently, I would like Somalia also to function in as many different urban centers as possible, without necessarily saying that we should have breakaway republics, and the reason is because it doesn’t make sense to break something that’s unbreakable. It’s not viable economically to have so many different mini-states, each selling the same services—they’re all selling milk and meat. What else do we have? If we are not together, we cannot balance the mountainous areas of the country, the geologically rich areas of the country, with the more fertile areas of the country.

Now, I’m also thinking that it doesn’t make sense to go different ways until two things have happened. First, the people in the breakaway areas of the country must be asked, in a just and transparent referendum, whether they would like to secede or not. Second, those who are being broken away from should also be asked to express their perspective on such critical issues. It’s like being married and then you wake up one morning and you declare simply that you want to leave. This raises many questions: on what basis are these people going away? On the basis that they were governed separately by a colonial power? Are we privileging the colonial philosophy? Are we degrading ourselves to the extent that we are willing to enshrine colonially-set boundaries? Now, if you said the breakaway Republic of Somaliland is going to have borders with Somalia, where are you going to put the border? If for instance, one kin group is broken in half, with parts in the Republic of Somaliland and others in the Republic of Somalia, how are you going to address it? It’s probably also worthwhile to mention that more and more countries in the world are getting together, forming larger unions, with federal possibilities. Look at western Europe. Why is it that Germany, France, England, Finland, and some of the most advanced technological countries are integrating? They are doing so because they’ve discovered that there are extraordinary benefits to unity.

AIS: You have earlier suggested that the Somali people—economically, culturally, socially—belong together, and their affinity with each other is unbreakable. Therefore, they have to solve their contemporary predicament together. Moreover, you have also ruled out the possibility of any kind of a viable leadership coming from three main sectors of the Somali male society — that is to say intellectuals, religious personalities, and elders — and have proposed that only women (who are not stained by the bloodiness of the times) could assume leadership. If one assumes that you are right, one still has to think about a new common sense or a paradigm that would rehabilitate communal association and overcome the deep alienation that is now part of the Somali mentality. Where do we go for that?

NF: I haven’t heard mea culpa from the men. I haven’t heard mea culpa from the elders or intellectuals. Such a public expression of deep regret is necessary for a society to reconstitute itself in ways that are honorable, acceptable, and with dignity. Here in South Africa, they’ve created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Now, I’m not saying that we have to create the same thing, but at least people would have to say, “You know, I have killed.” But when someone says to you, “I killed because this particular person belonged to a different blood community” and insists that he was right in doing this, then that person is a criminal insofar as I am concerned. I would say to him, “For God’s sake, until you accept that you are a criminal and ask for forgiveness from your God, your Creator, from the society at large, then I cannot accept you to be in a position of influence and power.” I am not saying that the intellectuals, the elders, and the Wadaads have to be cut off completely. What I am suggesting is, insofar as their actions have shown so far, they don’t seem to display foresight, political acumen. They don’t seem to give one confidence that glorious things will come from them. Nonetheless, it’s possible that once you reshuffle society, people who are now silent, those who have not spoken because the gun deafens them, may emerge from one or more of the four communities that we have mentioned, three of whom I have problems with, one less so. Now you cannot tell me, and I will not accept it from anyone, that Somali society, which for the past thirty-odd years has had the same visible so-called leaders—Egal has been there for God knows how long, so has the late elder Aideed, Ali Mahdi, and Abdullah Yusuf and everyone of the ambitious crowd — cannot find the right people for the new situation. What I am saying to you is this: why is it that the people who are accomplices in the ruin of Somalia are still being asked to lead it? You cannot ask someone who destroyed a house, who burnt it down, to reconstruct it. You need new blood.

AIS: Somali society now is more than the people inside the borders of Somalia, they are people in almost every continent of the world as a result of flight from the catastrophe. Are there any messages that you would like to send to/share with Somalis who are either refugees in different parts of the world or are making a diasporic future? What would you like to say to them given the discussion that we have had so far about the nature of Somali society and the contemporary reality?

NF: Well, what I know for a fact, and I’ve discovered it in my travels, is that when it rains in Mogadishu, Hargeisa, Borama, Bosaso, Baidao, and Beletwein, the umbrellas in Minneapolis, London, Rome, and other places are up! What I’d like to see is that those many Somalis

who’ve found their way to other countries and whose lives have now taken root, first nurse their lives, look after themselves, create a self-dignifying image of themselves. I would like them to, if necessary, forget about Somalia, while they are turning themselves into human

beings — complete human beings. I would like them, I guess in the irony of it, to remember the other Somalis who are among the internally displaced in Mogadishu, or wherever else they are. I’d like them to realize the fact that they have been given this golden opportunity to reconstruct their lives. If they are in America, I would like them to go to school, take their lives seriously, and educate themselves, and forget even calling themselves Somalis, if necessary, until they are worthy of the name which they invoke. There is no value in having two million Somalis who are at the bottom of every society they join. Whether in Sweden or Canada, the complaints about the Somalis ruin my hope and destroy my own self-image. So, I would like the overseas Somalis to aim for two things: to forget about Somalia, but also remember and only remember that they left so many people who haven’t been given that chance. So in the name of freedom and in the name of reason, they should rebuild their own minds. He who builds his/her own life in Toronto, in Minnesota, in London, in Rome, in Stockholm, is Somali. A good, working, educated Somali will, in the end, help Somalia, too. There is no use in those who continue talking about Somalia, gabbing about Somalia, without doing anything for themselves. Let them make something out of themselves, and maybe they will then do good for the rest.

AIS: There are those who suggest that writing ought to be apolitical, purely aesthetic, and must not get involved in immediate conflicts. On the other hand, some argue that writing and literature are eminently political. We’ve had a conversation about politics. Am I correct, then, to deduce that you are of the latter camp?

NF: Any human activity that involves more than two persons, and that touches on a topic that involves a third and a fourth party, is a political affair. In other words, marriage becomes a political act if a commoner were to marry the daughter of a king. Then it becomes a political act because of the obvious ramifications. I would say, therefore, that marriage is a political act, rape is a political act, inhuman activities that involve a third party and cut the lives of others, is a political act. But I am not interested in politics per se, and the reason is that really I find it very boring. I do not understand it; I cannot make it reasonable. I consider myself a person who is interested in the social animal — the human being. I am curious about my own origins and, certainly, want to know where I am being taken. In Somalia, I’ve never been involved in politics. But I have a few thoughts because I’m one of the few who had the opportunity to be educated in varied countries and to have had the opportunity to live in different and, perhaps, cosmopolitan continents. It is in this light that I speak, not as a politician.

AIS: What about the message to young Somalis, those who aspire to become writers and have the same kind of a burning ambition that you had as a young boy, what would you advise them? Are there any tricks to the trade that one needs to cultivate early on so that one can become successful like you?

NF: No writer can help another writer write. The only thing one can say is that they must write and write and write and they must speak and read and read, but they must pay no heed whatsoever to the rubbish that will often be pushed on them—that is, they belong to this kin or that family. These young people are the only hope that we have, especially the ones who have the opportunity to take control of their lives. I would say to them, “Please, please immerse yourself both in the culture and in the countries in which you live as well as know the culture from which your parents came.” It will be very beneficial later in their lives if they knew enough of where they came from, for that is critical for going forward. I want them to know that they belong to the entire Somali nation. I am looking forward to the rise of a great number of writers who will challenge some of my views, my logic, and my reasoning. But I have also read a novel by a young Somali, and I didn’t like it very much. I don’t like very much any writer who ruins an opportunity by taking belated and transient political sides.

AS: I wonder about the city of Mogadishu, of which you speak with a great deal of nostalgia, particularly its splendid urban culture, which is, perhaps, no more now — and the other places where you have lived such as Cape Town, where we are having this conversation today. Tell us about those two lives.

NF: Well, what I quite often say, and in fact I once wrote an article about the city of Mogadishu in the London Review of Books, is that what died with Mogadishu is the culture of cosmopolitanism, tolerance, the idea of living side by side with someone who you do not even like. This is what civil life is about. Now, Cape Town, as you know, has a very sad history, I suppose not totally different from Mogadishu — a city that has seen both conquest and segregation. But, I suppose a major difference between Cape Town and Mogadishu is this: despite the agony of the past, the majority of Cape Town’s residents are prospering now while Mogadishu has been completely destroyed. So what appeals to me about Cape Town is what used to appeal to me about Mogadishu. Mogadishu was a cosmopolitan city, the only one of its kind in the entire country. And it was cosmopolitan because different people came from different regions and each contributed to making Mogadishu what it became. This is what is happening in Cape Town right now, because in Cape Town you find lots of other Africans coming from different regions, and lots of Europeans, lots of people from the Middle East and Asia — each adding value to this cosmopolitanism. I would like to return to Mogadishu when the idea of cosmopolitanism is revived, the idea of “This city is mine and belongs to all of us.” And until this happens, I will hold in high esteem the ancient ideas of Mogadishu.

AIS: Do you have any personal regrets that you would like to share with our readers?

NF: I regret that I have not lived in Somalia for a long time. I regret that I did not go back to Somalia when I should have done so. I regret that I did not have the courage to speak up more forcefully. I regret that I haven’t made as much of a contribution to my society as I should have. But there is nothing one can do about all of these, under the circumstances. So, probably, my regrets are given half-heartedly.