Sunday 8 September 2024

African debt burden: who profits as austerity grips the continent?

Too often analysis of political unrest across Africa neglects the economic factors driving it. That exonerates those who profit at the continent’s expense and doesn’t allow us to think more constructively about solutions.

“The world never does anything for Africa,” says Khadidja Salah*, a Sudanese refugee. Salah travelled to Cairo for a medical visit before the war in her country began last spring. At the time, she was a professional in the gum arabic sector—one of the most crucial ingredients for companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi, among other western firms. When the war broke out, she was separated from her family, in a conflict that has now lasted more than a year and shows no signs of resolution. A mid-June article by Andres Schipani in the Financial Times already warned of the possibility that Sudan might fall into “the Somalia trap”:

“Somalia’s bloody descent in the 1990s started with a feud: two militia leaders together ousted a strongman ruler, then fell out. The battle for Mogadishu never really finished and, for decades, Somalia was left as the archetype of a failed state. For the Horn of Africa — and for Sudan in particular — it is a cautionary tale of violent infighting after regime change that seems bleakly relevant today.”

A couple of months ago, Faisal Ali warned in an article in Africa is a Country about the dangers of turning Somalia into a threatening spectre. He pointed out how the concept of chaos in Mogadishu is often used to exonerate key players from certain disasters. In this sense, Sudan is indeed on the path to becoming another Somalia: like other conflicts on the African continent, western analytical frameworks tend to focus on ethnic or personal issues to explain the ruthless struggles for absolute power. The international context in which these movements occur, or the pre-existing conditions that have accelerated their emergence, are rarely mentioned. Following a wave of coups in West Africa since the 2020 pandemic, with Sudan in civil war and Rwanda and the DRC on the brink of open conflict, the western reading is quite similar to that of the 1990s: once again, unrest, civil wars, massacres, and genocides are part of Africa’s daily reality. What is not discussed, then and now, is that the conflicts of the 1990s were, in part, a consequence of the economic reforms implemented during the previous decade.

Parallels with the Structural Adjustment Programmes of the 1980s

After gaining independence in the 1960s, many African states spent their first two decades as new nations trying to stand on their own feet. Training personnel to work in education, healthcare, and public administration was a top priority. With economies still structured in a colonial manner—exporting raw materials and importing manufactured goods—some countries embarked on industrialisation projects that were sometimes poorly conceived or accompanied by extravagant and unnecessary expenses. The oil crisis of 1973 had two major impacts on the global economy: for large oil importers (especially in the west), costs rose sharply and inflation surged; for exporters (such as Saudi Arabia), there was a significant increase in available funds. Western banks welcomed the influx of petrodollars and sought new markets to lend money beyond a stagnant Europe. It turned Wall Street into the world’s most important financial centre, giving America the power to enjoy what former French finance minister Jacques Rueff described as a “deficit without tears”. In the new international financial system the US could “give without taking, to lend without borrowing, and to acquire without paying,” Rueff said.

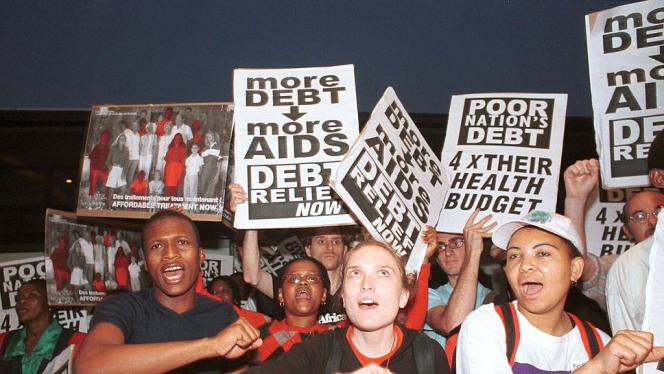

It was in this context that lending to some African countries accelerated. These nations were on a growth trajectory, needed to build their states, and offered good returns to lenders. Many of these loans had variable interest rates, and the danger of such agreements became apparent when Paul Volcker, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, raised interest rates to 19% to curb inflation in the United States in the 1980s. Suddenly, African countries faced a credit crunch, capital flight, and falling commodity prices, which undermined their ability to service their debts. Many turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as a lender of last resort, which proposed a series of austerity measures to reduce the role of the state in the economy and promote private sector growth. In a 2016 paper, which passed with little notice, the IMF itself conceded that its prescriptions for heavily indebted economies – almost always public sector cuts – hurt demand and worsen unemployment but are also often followed by “drops rather than by expansions in output.”

The outcome is evident for farmers like Musa Senghore. When he was a baby, he was carried on his mother’s back as she worked the rice fields in the Gambia. Today, in his seventies, he is still cultivating rice in the peri-urban areas of this west African country. In his youth, a hectare of rice yielded 1,900 kilos. At that time, a parastatal enterprise distributed cheaper fertiliser to farmers and bought the rice at the end of the harvest. Today, many farmers receive no assistance. The parastatal was closed during the structural adjustment era; now, a hectare in Gambia produces less than half of what it did forty years ago, in a country where the population has tripled. This year, a government project has subsidised fertiliser for some farmers like him: “This has been the best harvest in a long time. They covered up to 80% of the fertiliser cost. Without that help, the numbers just don’t add up,” says Senghore. In Gambia, the economic fragility following structural adjustment plans led to a military coup in 1994 and a consequent dictatorship that lasted until 2016.

In neighbouring countries in the region, such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, over a decade of civil wars ensued. In Rwanda, a few years before the genocide, external debt payments increased dramatically, and the IMF staff recommended that Rwanda devalue its currency by up to 40%. The country was encouraged to focus on export crops like tea and coffee. When prices plummeted in the global market—and fuel prices spiked by up to 79%—the social situation deteriorated significantly. This created fertile ground for the ideas of Hutu Power, advocating ethnic cleansing against the Tutsi population, to take root and ultimately result in the 1994 genocide.

Debt repayments exceed Official Development Assistance

After the 2008 crisis, many banks and investors turned to African bonds as a new source of profit. With interest rates near 0% in Europe and the United States, countries like Zambia, Senegal, Ivory Coast, and Kenya were offering rates above 6%. Fuelled by China’s economic growth, many African countries witnessed a sharp rise in the prices of their primary exports—unprocessed raw materials. This was referred to as the “commodities boom”, and even the 2008 financial crisis couldn’t stop it.” Between 2010 and 2021, African debt held by bondholders increased from $32 billion to $143 billion. The outcome has evoked memories of the 1980s: a sudden increase in interest rates in the west abruptly halted this trade. The resulting aftermath has spread across the continent, with nations spending recent years anxiously anticipating the approaching moment of repayment.

The new debt crisis affecting many countries on the continent is manifesting in various political ways. Mamadou Thiam is a precariously employed teacher in Dakar, Senegal’s capital, and returns each year to his home region of Tambacounda in the southeast to cultivate peanuts. Thiam describes the business generated around fertiliser, both a consequence and cause of the dysfunctions in the agricultural sector: “We queue for hours to get the sacks distributed by the government, but some people end up selling them at market price in the Gambia to make more money.” Thiam voted for the opposition in last March’s elections. He was among the Senegalese who helped bring a new government to power, hoping it can steer the country out of its economic troubles. Meanwhile, other countries such as Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali have experienced several coups since the pandemic and are now governed by military juntas. They all share a common issue: their debt payments and interest obligations have soared, and the increase in western interest rates has hampered their ability to refinance. This time, they face the same situation as in the 1980s, but with weaker social structures and the major consequence of that decade’s crisis: an accumulation of population in urban areas, where the majority must survive in the informal economy.

In 2024, according to World Bank data, Africa will pay $64 billion in debt servicing. This amount exceeds the entire Official Development Assistance the continent received in 2022, which stood at around $60 billion. Similar to the 1980s, the rise in interest rates has had a detrimental impact on African countries and other developing nations, as explained by the World Bank in its annual report on global debt: “As interest rates climbed in advanced economies, private creditors followed the money in 2022: they largely withdrew from developing countries, pulling out US$185 billion more in principal repayments than they disbursed in loans.”

With higher interest rates and reduced private financing, the World Bank and IMF have stepped in to lend money to African countries at lower interest rates. A portion of this funding will prevent defaults, but in exchange, African governments will have to implement austerity measures. Part of these funds will also be used to repay western investment funds and banks. These measures will be challenging to implement. In Kenya, which spends twice as much on debt interest as on healthcare, attempts to raise taxes on basic goods have led to riots and an attack on parliament. Their latest bond sold to the private sector already carried over 10% annual interest, and Kenyan authorities fear that without IMF support, future bond sales to the private sector will come at even higher costs.

Caught between the IMF and the private sector, and with Chinese loans dwindling, the economic sovereignty of dozens of African countries hangs in the balance. With median ages often below 20 years old, some youth are challenging their governments, refusing to endure what their predecessors faced in the 1980s. In response, authorities are cutting off internet access and increasing police presence in the streets to push through agreed adjustment plans. Western banks promptly collect the money stipulated in the contracts. And Western media will wonder why, once again, violence has returned to Africa, which they will not hesitate to describe, once more, as a “hopeless continent”.

Khadidja Salah’s* name was changed to protect her identity.