Thursday 21 November 2024

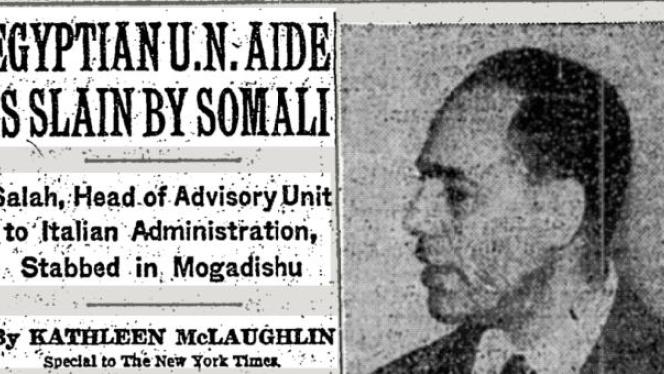

The mysterious killing of Kamal Al Din Salah in Mogadishu

In 1957, a controversial Egyptian diplomat was murdered in Mogadishu. The police investigation that followed stoked dangerous tensions within the Somali nationalist movement, but it also exposed the weakness of the colonial state.

On April 16 1957, at around 12:45pm, Kamal Al Din Salah crossed a quiet courtyard in central Mogadishu. Smartly dressed in a suit and tie, the Egyptian diplomat had just chaired a meeting of the United Nations Advisory Council of Somalia – an international body designed to supervise the Italian colony and prepare it for political independence. Before lunch, he was scheduled to meet with the Egyptian consul. As Salah waited in the courtyard, however, a young man approached and threw him to the ground. Passers-by watched in horror as the attacker stabbed him ten times, puncturing his liver and lungs and leaving him bleeding on the ground. Consulate staff rushed the diplomat to hospital, but it was too late. Within minutes of arrival, Salah was dead.

The motive behind the murder remains unclear. Some insisted that it was a personal matter, others claimed that his death was retribution for Egypt’s attempts to interfere with Somali nationalist politics. A long police investigation attempted to settle the case conclusively, but inconsistent testimony, missing evidence, and a chaotic criminal trial only deepened existing tensions. Politicians, diplomats and publicists, meanwhile, attempted to manipulate Salah’s legacy to support their own causes. Ordinary Somalis took to the streets in protest against the murder, but others criticised Egypt sharply for trying to exercise control over the nationalist movement. By July 1957, Italian authorities in Somalia were forced to admit that the situation had escalated far beyond their control. The killing of Kamal Al Din Salah had sparked a political crisis that threatened the very foundations of the colonial state.

This crisis reflected the unusual political situation of late colonial Somalia. The area between Bari and Jubaland had initially been an Italian colony. During the second world war, it became a staging ground for invasions into Ethiopia and was occupied by the British Army in 1941. After the war, however, the victorious Allied Powers failed to agree on the colony’s future. The region was eventually transferred to the UN Trusteeship Council in 1950, which invited the Italian government to return and rule it on their behalf. However, the newly formed ‘Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian Administration’ would also be supervised by an Advisory Council led by representatives of three UN member states – the Philippines, Colombia, and Egypt – who would encourage political reform and evaluate whether the territory was being governed according to international standards.

UN officials imagined the trustee system as a way to encourage the rapid development of Somali society. Italian officials were instructed to develop the Somali economy and introduce thousands of local officials into the colonial administration. The UN agreement also required the Italian administration to “foster the development of free political institutions”, which culminated in Somalia’s first municipal elections in 1954 and its first parliamentary elections in 1956.

Significantly, the UN had also set a deadline for Somali independence – 1960 – and instructed the Advisory Council to make sure that this target would not be missed. In practice, however, this experiment in moral colonialism often fell short of its paternalistic rhetoric. Italian officials living in functionally segregated communities still dominated the territory’s financial, legal and political institutions while the Somali parliament was relegated to a purely advisory role. As independence approached, Italian officials attempted to make alliances with Somali politicians to ease the transfer of power and retain a level of influence in the new regime.

Italy, however, was not the only state attempting to influence Somali politics. In 1950, Egypt had been an uncontroversial choice for the Advisory Council. During the reign of King Farouk, the nation had aligned itself with the United Kingdom and the other Allied powers. In 1952, however, Farouk was overthrown by a group of army officers seeking to modernise and strengthen the country. By 1954, Egypt had become a republic under the rule of Gamal Abdel Nasser – a charismatic socialist who aimed to undermine Europe’s influence across Asia and Africa while securing valuable allies for his own government. To do so, Egyptian officials began to give support to anti-colonial activists from Cape Town to Cameroon. As Radio Cairo broadcast speeches and songs which urged their listeners to rise up against imperialism, political agents began channelling munitions and funding to militant groups across the world.

Egyptian officials began to give support to anti-colonial activists from Cape Town to Cameroon. As Radio Cairo broadcast speeches and songs which urged their listeners to rise up against imperialism, political agents began channelling munitions and funding to militant groups across the world.

Kamal Al Din Salah arrived in Mogadishu in November 1954 to fill the Egyptian seat on the UN Advisory Council. At that time, Egyptian interest in Somali decolonisation was based in political and linguistic ties. The Nasser government expected Somalia to align itself with the Arab League after independence, and the high number of Arabic speakers in the Somali elite reduced the need for translators. The nationalisation of the Suez Canal in 1956, and Egypt’s defence against French, British and Israeli troops during the Suez Crisis, would later allow Nasser to present himself as a hero of the postcolonial world – an image he cultivated that raised Egypt’s international standing.

Somalia also had strategic importance to Egypt. The northern coast of the Trust Territory was close to the Aden Protectorate, a British colony and one of the most important naval bases in the region. It was also close to British Somaliland and the French Somali Coast (now Djibouti). As long as these four territories remained under colonial control, argued Mohamed Fayek at Egypt’s Bureau of African Affairs, the colonial powers could threaten to cut them off from vital trade with the Middle East and South Asia. Friendly relations with an independent Pan-Somali state, by contrast, promised to secure Egypt’s access to valuable international markets. Government support for a Greater Somalia also harmed Nasser’s Ethiopian rivals by creating unrest in Ogaden, a large region with a Muslim Somali majority.

Friendly relations with an independent Pan-Somali state, by contrast, promised to secure Egypt’s access to valuable international markets. Government support for a Greater Somalia also harmed Nasser’s Ethiopian rivals by creating unrest in Ogaden, a large region with a Muslim Somali majority.

On the surface, Salah’s activities were similar to those of the Colombian and Philippine representatives. Beyond his official duties, however, he also began engaging in political work on behalf of the Egyptian state. Salah began distributing scholarships to universities in Cairo, aiming to reduce Somali reliance on colonial scholarships in Rome, and argued that Somalis should reject European trade in favour of regional partners. Archival documents uncovered by the historian Antonio Morone reveal that he also worked closely with Egypt’s Foreign Ministry and Ministry of National Guidance to coordinate a media campaign attacking “Western colonialist manoeuvres” throughout the Horn of Africa. The memoirs of the African Affairs advisor Mohamed Fayek also reveal that Egyptian officials also provided free legal and political advice to anti-colonial nationalist groups. Salah spoke frequently at mosques and religious gatherings, depicting colonial officials as enemies of Islam who would create conflict across Somalia. On the night before his murder, he had also spoken at a small political rally, encouraging his audience to support a union of the Somali-speaking peoples.

This political work was not always appreciated. Salah also attracted criticism from the colonial authorities, who grew concerned that his subversive political work had the potential to radicalise the nationalist movement against their own rule. The Advisory Council, complained the British consul in Mogadishu, was the “most effective weapon” for increasing Nasser’s influence over the Somali territories. The Italian government agreed. “Egyptian influence [is] aggressive”, complained the Trust Territory Administrator Enrico Martino in 1955, “especially through Kamal Al Din Salah, who, in private, spares no criticism of our administration.” Many Somalis, too, believed that Egypt was exerting a harmful influence on nationalist politics. In 1956 and 1957, Salah had to defend himself against the accusation that he was “interfering in the political and economic life of Somalia” and “systematically attempting to lure the populace into membership of the Arab League.”

On April 17, Salah’s body was taken to the Advisory Council building to lie in state.

Salah also attracted criticism from the colonial authorities, who grew concerned that his subversive political work had the potential to radicalise the nationalist movement against their own rule.

The murder had attracted deep public interest, and British observers reported that an “immense crowd” of Somalis had gathered to pay their respects to the murdered diplomat. Given the delicate political situation, the colonial government tried to keep a safe distance from the police investigation while calming the public mood. When the police apprehended the murderer, a young Somali named Mohamed Sheikh Abdurahman, the Italian Administration quickly released a press statement claiming that the killing had been motivated by personal grievances. Abdurahman had previously been a student in Cairo, they revealed - but he had behaved poorly, and the Egyptian government had expelled him from the country. The most likely motive for the killing was revenge against a prominent Egyptian official, they said.

Over the next few days, however, Abdurahman began to contradict his own testimony. On April 22, he appeared before the public prosecutor claiming that he had been hired to kill Salah by the Hizbia Digil Mirifle (HDM), the main opposition party in the Trust Territory. In response, the colonial police arrested around thirty HDM members, and the government asked the prosecutor to proceed with a criminal case against two prominent deputies. However, on 3 May, Abdurahman retracted his earlier statement, claiming that the police had pressured him into making false claims against the HDM. He changed his testimony again on 10 May, returning to his earlier claims about an opposition plot.

It is certainly possible that Salah had been targeted for political reasons. His closest ties were with the Somali Youth Movement (SYL), a nationalist political party which had dominated Somali politics since the 1940s and led the country throughout the first post-independence decade. The SYL were nominally opposed to tribalism and clannism, but they drew their greatest strength from urban professionals and pastoral communities in the north of the Trust Territory. The HDM, by contrast, represented traders and agricultural communities in the south. While they were broadly supportive of Somali nationalism, they were suspicious of the SYL and of any political union that could concentrate the power of the northern clans. This rivalry with the SYL had become violent in 1953, and tensions between the two groups still ran high. During the investigation, the police also claimed to have discovered a large sum of money at Abdurahman’s home in Baidoa – evidence which suggested that he may have been paid for the killing.

During the investigation, the police also claimed to have discovered a large sum of money at Abdurahman’s home in Baidoa – evidence which suggested that he may have been paid for the killing.

Others, however, raised serious doubts about the supposed conspiracy. Abdurahman had a history of violence and violently attacked a co-worker, making a personal motive plausible. At times, he also claimed that detectives had forged his statements about the HDM deputies and forced him to sign them. In private, British observers speculated that the police had fabricated the potential political motive in order to undermine the opposition group. The Italian administration had been highly reluctant to investigate such a sensitive case themselves, so the case was left to a group of Somali officers—many of whom had close ties to the SYL and a vested interest in arresting prominent opposition leaders. “There cannot be much doubt”, argued the British Consul-General Anthony Kendall, “about the flimsiness of the accusation against the two deputies of the Hizbia and the party itself. […] The Italian administration, which cannot escape its responsibility for occurrences here, has proven craven when faced by a determined Somali stand.”

Meanwhile, the Egyptian government was turning the murder into the centerpiece of a new political campaign. With the help of Somali students in Egypt, Radio Cairo’s services in Arabic and Somali began depicting Salah as a “martyr for independence” and encouraging Somalis to protest outside the UN building in Mogadishu. Anonymous pamphlets denouncing the Italian administration were also smuggled into the territory, accusing the Italian secret service of orchestrating the murder. For Muhammad Hassan Al Zayyat, who replaced Salah as Egypt’s representative on the Advisory Council, the aftermath of the murder provided an important opportunity to secure “the correct political and national orientation” for an independent Somalia. He recommended strengthening Egypt’s secretive relationship with the SYL, providing support and advice “without giving the impression of interfering in the internal affairs of the party.”

The Egyptian government also sent the African Affairs advisor Mohamed Fayek to Mogadishu – partly to support Al Zayyat and partly to conduct his own investigation of the murder. Fayek was deeply critical of the colonial police, believing that Somali or Italian officials would inevitably manipulate the evidence to suit their own ends. The Italian government attempted to expel him from the Trust Territory, but diplomatic pressure from Egypt and a mass demonstration in Mogadishu pressured the colonial administration into allowing Fayek to stay. Ultimately, however, it is also possible that Fayek’s intervention was intended to manipulate the case and remove evidence of Salah’s political work. The Egyptian government wasted no time in sealing Salah’s desk, seemingly worried that it contained sensitive documentation about his political work. Some also accused the Egyptians of hiding a personal letter from Abdurahman to Salah which may have shed light on the motives for the assassination.

Some also accused the Egyptians of hiding a personal letter from Abdurahman to Salah which may have shed light on the motives for the assassination.

These tensions came to a head during a chaotic criminal trial. Speaking to the courtroom in early July, Abdurahman changed his story several times—first claiming that he had been paid to kill Salah, then claiming that nobody had incited him, and later returning to his accusations against the two deputies. Ultimately, however, the public prosecutor’s case against the HDM proved unconvincing. His Egyptian counsel, Rashad Ramzi, then began to dominate the courtroom, ignoring the charges against the HDM entirely and breaking protocol by cross-examining witnesses himself. Political factors also threatened to influence the outcome of the trial. A month earlier, judges, ministers, and senior SYL leaders had all received anonymous threats that they would be assassinated if the two HDM deputies were not acquitted. Meanwhile, the Egyptian government warned that any failure to convict Abdurahman would lead to severe diplomatic consequences. Abdurahman was eventually sentenced to twenty years in prison, and the two HDM deputies were acquitted. The chaotic proceedings, however, had already done significant damage to the colonial government’s credibility. “[The] whole farce got completely out of hand,” reflected Arthur Cuninghame at the British Foreign Office, “and the Italian authorities are now held as scapegoats. They have played into the hands of the Egyptians.”

By mid-July, this controversy had escalated into a major political crisis. The guilty verdict against Abdurahman had been expected, but many interpreted the acquittal of the HDM deputies as evidence of colonial favouritism. As the trial concluded, the Italian government resorted to a show of force, patrolling Mogadishu with armored cars to deter pro-Egyptian demonstrations. That same month, the leadership of the SYL was won by Haaji Muhammad Hussein, a radical nationalist with strong ties to the Nasser government. Hussein, who at the time of his election was living in Egypt and working as an announcer on Cairo’s Somali Service, advocated for a complete break with imperial authority and the unification of the Somali peoples. Concerned about the potential for militant anti-colonial activity, the Italian administration briefly considered giving up their trusteeship of Somalia and returning the territory to the UN for mediation.

Hussein, who at the time of his election was living in Egypt and working as an announcer on Cairo’s Somali Service, advocated for a complete break with imperial authority and the unification of the Somali peoples.

This radical moment, however, was ultimately short-lived. Haaji Muhammad Hussein proved popular with Egyptian diplomats but failed to win support from within his own party. In April 1958 he was ousted as the party leader by Aden Abdulle Osman, the president of the Somali Legislative Assembly, who argued that militant anti-colonial rhetoric risked upsetting international donors and leading the nationalist movement into diplomatic isolation. The Italian government, in turn, prepared a major technical assistance package for Somalia with the assistance of the United States. The deal, which included some $2,000,000 in funding and 100 university scholarships, was announced just days before the municipal elections of 1958 in an attempt to bolster support for pro-western candidates. Hussein attempted to regain some of his former influence with a new party, the Greater Somalia League, but the group was closely monitored and suppressed by the colonial police. On July 1 1960, the Somali Republic declared independence with Aden Abdulle Osman as its first president.

Sixty-seven years on and the murder of Kamal Al Din Salah remains a mystery. Silences in the historical record and the loss of key evidence mean that the real motives of his killer may never be known. The scandal which surrounded his assassination, however, tells a compelling story about powerful international actors and a nervous colonial state. Salah commanded popular attention because he promised support to the nationalist movement in Somalia and solidarity with those struggling for independence. However, he also symbolised an ambitious and paternalistic form of diplomacy that sought to draw Somalia into Egypt’s orbit. In the weeks that followed his death, Somalis and Egyptians alike used his image to promote their own political ideals. To this day, Egyptian politicians still refer to Salah in their diplomacy in Somalia, citing him as a national hero and a martyr for Somali independence.

The scandal also played an influential role in exposing the weakness of the Trust Territory administration. Italian attempts to remain detached from the scandal backfired dramatically, allowing a political crisis to spiral out of control. By 1958, they had inadvertently given fuel to militant nationalism and were forced to make heavy investments in Somalia to retain their own influence. In life, Salah had preached about the failure of colonial rule to bring about peace in Somalia. In death, he had proved it.