Tuesday 19 November 2024

Ethiopia, Red Sea and the Somali Republic(s)

Somalis have a contentious relationship with Ethiopia and the memorandum has stirred historical anxieties about their relationship with their larger neighbour.

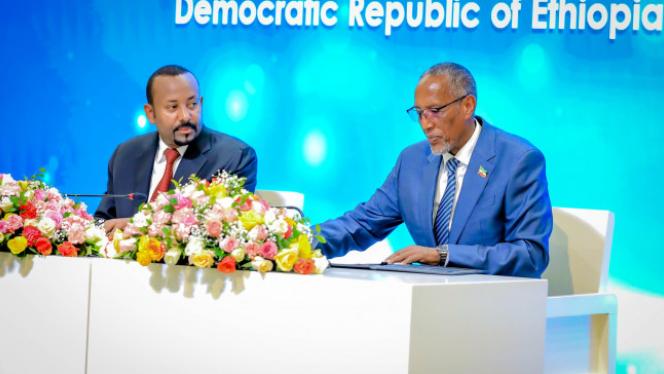

It was all smiles in Addis Ababa on New Year’s Day when Somaliland’s president Muse Bihi and Ethiopia’s prime minister stepped out after a tête-à-tête. The two leaders sat down before they announced a memorandum of understanding which would put them on the path to realising their respective national aspirations.

Muse Bihi set out the few details we know so far. Ethiopia, he said, would lease a naval base on the Gulf of Aden and Somaliland would take its first big step on its quest to statehood, with Ethiopian recognition of its independence from Somalia. Welcoming the deal, Ahmed told an audience of officials from both sides: “This is the good news we bring to all the people of Ethiopia, Somaliland and all the peace and development loving people on this first day of the new year.”

Though the full details of the memorandum haven’t been made public, communiques released afterwards said Somaliland agreed to lease 20km of sea access to Ethiopia for a naval base and in exchange Hargeisa would receive a share of Ethiopia’s lucrative flagship carrier, Ethiopian Airlines. Bihi also added that Ethiopia “will become the first state to recognize Somaliland”, which if true would see Somalia lose almost a third of its territory. Ethiopia has said that lease would be “permanent”, which is possibly why officials in Mogadishu have described it as an annexation, whereas Somaliland has said the lease is only for 50 years.

Somaliland’s information hailed the deal as a “game changer”, as the ministry for foreign affairs described it as a “diplomatic milestone”. In Ethiopia, irrigation minister Birhanu M Lenjiso posted: “Recognition is a precious currency!” There was jubilation on both sides, as people quickly took to the streets of Addis Ababa and Hargeisa to party.

In Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital, however, a storm was brewing that would threaten to torpedo the nascent agreement and eventually force Ethiopia to roll back its rhetoric. That evening Somalia said it would convene an emergency meeting of its cabinet and a joint session of parliament. By the next morning, the Somali government had announced its rejection of the port deal as “null and void” describing it as an act of “aggression” by Ethiopia and began using all diplomatic channels to solicit support from its partners.

“The outcry from Somalis everywhere is huge”, one diplomat from the region told Geeska. Whilst the east African regional body IGAD made a meek statement balancing the interests of its various members, the EU and Arab League both voiced support for Somalia’s territorial integrity, warning against any attempt to hastily change borders. The US and UK also followed suit, warning that the deal would bolster al-Shabaab and in doing so demonstrated their inability to see any issue in Africa outside a security lens.

The agreement, which isn’t yet legally binding for either side, has inflamed tensions across the Horn of Africa, dividing publics in Somalia, Somaliland and Ethiopia. This played out dramatically during a televised interview in which one man who was defending the deal was attacked live on air, illustrating the superficial diplomatic rapprochement between Ethiopians and Somalis.

Somalia and Ethiopia have a history marred by repeated bouts of military conflict, with Somalis often accusing their larger neighbour of harbouring imperial intentions to subjugate their country in a bid to gain sea access; and Ethiopia fearing Somalia’s irredentist ambitions in the country’s Somali populated east.

The response by Mogadishu has been fierce, promoting a surge in Somali nationalist sentiment across the Horn; even costing Muse Bihi a member of his cabinet. Somaliland defence minister, Abdiqani Mohamud Ateye, made mention of what he called Ethiopia’s occupation of Somali territories as he resigned from his post over the agreement. In an interview with Horyaal TV Ateye added: “The number one enemy of the Somali people that God gave them in the Horn of Africa is Ethiopia. Every Somali, whether young or old, knows this.”

In a speech following Friday prayers, Hassan Sheikh Mahmoud, similarly mentioned the fact that Ethiopia and Somalia hadn’t settled their border along the north-south axis, which remains an administrative boundary, raising the spectre of its 1977 invasion. One of Mahmoud’s advisers even warned that war was on the cards in an interview with the Guardian.

Few analysts take this seriously; the Somali war threat appears more like the warning of a madman threatening to shoot himself if his interlocutors don’t meet his demand. But as al-Shabaab manoeuvres to exploit the situation, Mahmoud is left with little choice. Ali Mohamud Rage ‘Dheere’ has called on Somalis to “stand up in defence of your country.” As Somali cabinet minister Aw Hirsi correctly pointed out in a recent piece with the East African, “al-Shabaab has already started to manipulate the situation and is primed to recruit youth in the name of religion and pan-Somalism.”

Ethiopia’s move undermines its own collaborative efforts with Somali security forces to rid its neighbour of al-Shabaab, an organisation which it must be stressed also poses a threat to Addis Ababa. Abiy Ahmed is probably gambling that given al-Shabaab’s existence is partly due to the presence of Ethiopian troops in Somalia in the first place – as Somalia’s deputy prime minister himself recently pointed out – and that pulling them out would only embolden the organisation to attack the Ethiopian mainland, al-Shabaab’s threats don’t make a difference either way. Contrary to claims by Somali officials, a defeat of al-Shabaab isn’t on the horizon and Ethiopia will be fighting it for the foreseeable future whatever happens. You might as well exploit Somali divisions and conduct that fight with the advantage of your own port. Abiy Ahmed is an established merchant of chaos; he won't lose sleep over heightened conflict in Somalia.

Nor is Ethiopia perturbed by Somalia calling its allies in Ankara and Cairo to support it, the Middle East’s leading superpowers. Both have said they’ll stand by Somalia with Turkey even signing a defence pact. Shortly after the deal was inked, Somalia’s defence minister, Abdulkadir Mohamed Nur, took a photo next to Haluk and Selçuk Bayraktar, the famed makers of the Bayraktar drone, in what was a barely veiled signal to Abiy Ahmed.

It is in Somaliland, however, where the stakes are highest. In fairness to Muse Bihi, his reign came during a difficult time to be in office in Hargeisa.

A generation of Somalilanders have matured nursing hopes of imminent independence which hasn’t come; it has entered the fray of partisan politics in the US, cultivating ties with extreme MAGA Republicans to the detriment of ties with Democrats; picking sides in the Gulf Crisis and the US’s cold war with China have made Hargeisa unnecessarily powerful enemies; the Covid pandemic put life on pause and undermined global economic output; and Bihi’s mismanagement of the Las Anod conflict has lost his country nearly a third of its territory.

Compared to the standards set by his forebears who made great strides before they passed on the baton, Muse Bihi’s scorecard isn’t great. Other than the upgrades at Berbera port, he doesn’t have much to show for his term and he doesn’t appear satisfied with being the president who held the boat steady in turbulent seas. Neither Sudan nor Ethiopia have come off the back of the Trump era in better shape – one has collapsed and the other fought a series of wars against its own people. Consolidating Somaliland’s existing gains would have been considered a great achievement if Bihi was thinking in grand-historical terms.

Muse Bihi's decision to sign this memorandum might be thought of as the geopolitical equivalent of a shot at the buzzer, but unlike Steph Curry, this one may be off the mark. He is two years over his mandate with pressure growing for elections and his term is unlikely to be fondly remembered by Somalilanders whose expectations of progress on the independence file haven’t been met.

His decision has also sparked widespread dissent with Somaliland, a first for a republic which has enjoyed relative peace and buy-in from communities under its control. Large protests broke out a week after the deal in Borama as rumours spread, partially fed by Somali officials, that a corridor was also going to be handed to Ethiopia connecting the coast to its border. A group of politicians in Somaliland’s House of Elders have come out in opposition to the deal, further undermining it. In a joint statement read by Nur Omar Rayale, the elders from the Awdal region said: the “people in Awdal and Salal regions do not accept Ethiopia to be given land, sea or access [to sea]” in Somaliland.

The greatest risk here however is that Ethiopia reneges on the most critical aspect of this deal. Recognition. Ethiopian officials have hinted at their support, but no senior official has publicly confirmed this. The most we’ve seen is Mesganu Arga Moach, Ethiopia’s state minister for foreign affairs, post on his X account that he “welcomes” Somaliland’s statement which claims Ethiopia guaranteed international recognition. Somaliland’s foreign minister, Essa Kayd, has laid out the stakes for Ethiopia of not meeting their key demand, warning Ahmed that without recognition “nothing is going to happen.”

As with all shots at the buzzer, either it drops, and you enjoy the glory of having snatched victory from the jaws of defeat or you risk earning the ire of your teammates who might have preferred an approach which could allow a better shot on target. If Bihi succeeds, he will have made the greatest contribution to lifting Somaliland out of its international isolation – a feat which will cement his place in Somaliland’s history and the region’s. Failure, however, will exacerbate growing divisions in Somaliland about its future and almost certainly embolden the expansionist tendency of the Horn of Africa’s most formidable power. As Nureddin Farah warned in his seminal essay, Which way to the sea, “the players on the political scene in the Somali peninsula may be different. Yet, the wish on the part of Ethiopia to make a claim one way or another to the coast or to have easy access to it continues.”