Wednesday 20 November 2024

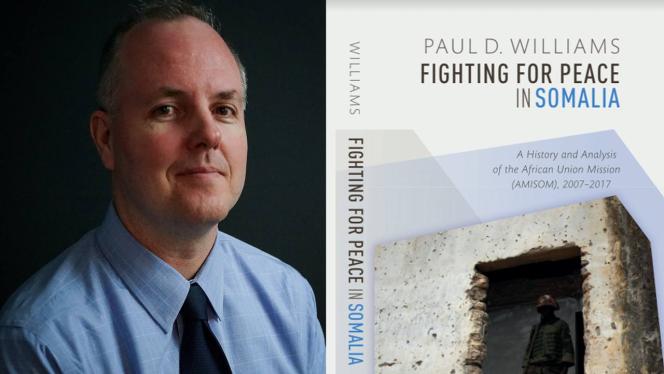

Fighting For Peace in Somalia: interview with Paul D Williams on Amisom

American academic Paul D. Williams discusses with Geeska his comprehensive study of the African peacekeeping mission Amisom, which was operational in Somalia from 2007 to 2022.

The African Union Mission in Somalia (more commonly known by its acronym Amisom) was the AU’s costliest, more dangerous and largest peacekeeping operation by a “considerable margin,” writes Paul D Williams, in his book on the force, Fighting for Peace in Somalia. By 2017, Williams reports, Amisom had become the world’s longest running peacekeeping mission, with over 20,000 troops present in Somalia at its peak, having spent over a decade in the country. Troop Contributing Countries initially included Uganda, Burundi and then expanded to Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya, which were assigned to separate security sectors across Somalia. Sierra Leone also briefly deployed troops in 2013.

Established in 2007 at the request of the then Transitional Federal Government led by Abdullahi Yusuf, Amisom initially consisted of a Ugandan force airlifted into Mogadishu. Its origins were as humble as its lofty goal: stabilising a country that had been in a state of civil war for almost two decades. Prior to Amisom, both the US and the UN had failed, and among Somali initiatives, only the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC) had moderate success in stabilising Mogadishu.

While the challenges to pacifying Somalia were initially posed by indignant warlords, Ethiopia’s invasion in 2006 to dislodge the UIC led to the emergence of al-Shabaab as a dynamic, well-resourced, and adaptable security threat. al-Shabaab capitalised on anti-Ethiopian and anti-Amisom sentiments to rally support, declaring Amisom an occupying force, and its Somali allies infidels.

The force has protected the Somali government, which has grown in capacity and sophistication over the years. Amisom has participated in counterinsurgency and stabilisation operations, expanding the areas under its control in collaboration with Somali forces. In his book Williams writes: “AMISOM gradually evolved from occupying just a handful of strategic locations in Mogadishu to covering an area of operations that encompassed the whole of south-central Somalia, a region roughly the size of Iraq.”

These achievements have won Amisom some plaudits. But it’s record has been chequered by civilian casualties and allegations of sexual abuse. Williams’ book also tackles this issue, looking at resource constraints which meant Amisom’s police and civilian components which would have been responsible for Protection of Civilians (POC) protocols weren’t prioritised, let alone questions of Amisom having enough troops. One former officer told him that a “force that cannot protect itself is unlikely to do well at protecting civilians.”

Amisom’s mandate has now ended, and ATMIS has picked up where it left off. Paul D. Williams, a professor of International Affairs at George Washington University, in the US capital, examines Amisom’s record in Somalia in an interview with Geeska.

Faisal Ali: Most people who look at Somalia through a security lens tend to focus on al-Shabaab which typically gets more attention because of the explosive subject matter. I'm curious about what led you to produce this hefty study on Amisom instead, and treat it at book length?

Paul D Williams: Since my expertise is on peacekeeping operations, Amisom was the obvious choice for my book. Amisom became the African Union’s longest, largest, most costly, and most deadly operation, so it deserved serious attention. During the late 2000s and 2010s, the mission also became an important barometer for a broader set of international debates. First, about how peacekeepers could conduct counterinsurgency and counterterrorism. Second, about the challenges of what the UN Secretary-General called “partnership peacekeeping”—where the African Union, United Nations, and European Union worked together to keep Amisom running.

FA: One of the topics you cover in the book is what motivated Somalia's neighbours to embark on such a thankless and dangerous mission - the most dangerous one in the world you write - which has had serious security implications for them too. Did anything surprise or leap out at you about what motivated these states to put their troops in harm's way in Somalia?

PDW: Somalia’s neighbours did eventually join Amisom but not initially. For its first four years, Amisom’s two contributing countries were not Somalia’s frontline states, but rather Uganda and Burundi. It was only in 2011 that Djibouti and Kenya deployed troops in Amisom. In Kenya’s case, it came after initially conducting a unilateral intervention into southern Somalia separate from Amisom. Similarly, in 2014, some Ethiopian troops finally joined Amisom as part of a “temporary surge” after having reentered Somalia in late 2011. This suggests that both Kenya and Ethiopia were primarily motivated to deploy troops in Somalia for national security reasons, basically to try and reduce the threat posed by al-Shabaab. However, they came to realise that joining Amisom would enhance the political legitimacy of their operations, as well as provide financial and logistical assistance.

FA: How have the interests of these countries, especially when the political centre of gravity switched to 'frontline states' (i.e. Kenya, Ethiopia) as you observe in the mid-2010s, impacted the way Amisom's goals in Somalia?

PDW: I would argue not that much. Amisom’s main strategic objectives have stayed remarkably stable since its initial deployment in 2007. The mission has always focused on protecting the Somali federal authorities, degrading al-Shabaab, and encouraging political reconciliation. All these priorities continued, although later Amisom added more emphasis on helping to build the Somali security forces. Arguably the biggest change was Amisom stopped being a mission in one city (Mogadishu) which was effectively run by Uganda, to a mission stretched across the vast terrain of south-central Somalia with more autonomous contributing countries. This forced Amisom to go mobile to recover population centres from al-Shabaab and resulted in the mission establishing a large network of some 80 operating bases.

FA: What enduring impacts do you believe Amisom has had on the political and security landscape in Somalia?

PDW: I’d point to seven main successes for Amisom. First, it facilitated the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops from Mogadishu by early 2009. This was very important because it was the single biggest source of al-Shabaab support. Second, Amisom achieved its mandate of protecting the Transitional and then Federal Government of Somalia from al-Shabaab. Third, by the end of 2011, Amisom had pushed al-Shabaab’s main forces out of Mogadishu and its environs. Fourth, during 2012 and 2013, Amisom recovered dozens of settlements from al-Shabaab. A fifth success was providing security to facilitate the establishment of Somalia’s Federal Member States. Sixth, the mission has provided protection for the international diplomatic community in Somalia. And, seventh, Amisom had a long history of sharing its medical facilities, rations, and water supplies with local populations, and helping to build infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and buildings that benefit all Somalis.

FA: One major challenge Amisom faced is the consequence of the misconduct of its own forces, including civilian deaths, and which facilitated hostile propaganda. How did Amisom deal with these challenges?

PDW: You’re correct, some AU peacekeepers did harm local civilians. This was mainly through incidents of indirect fire and mistaken identity, and in some cases in traffic accidents. Some AU personnel were also accused of various forms of sexual exploitation and abuse. All these things generated negative perceptions of the mission amongst the local population.

In response, the mission and its contributing countries implemented various “conduct and discipline” procedures, including setting up boards of inquiry and Uganda has court martialed a few of its soldiers. Amisom also changed its indirect fire policy and established a Civilian Casualty Tracking and Response Cell to monitor civilian harm, although the mission only very rarely gave reparations to victims. In general, Amisom struggled to tell its positive stories and its achievements to the Somali population at large, in part because it invested very few resources in strategic communications capabilities.

FA: One of the arguments in your book is that the mandated goal of the peacekeepers was complicated by the political dysfunction in Mogadishu and its attendant impact on the Somali security sector. How did the mission attempt to tackle this problem, especially considering sensitive questions around the formal sovereignty of the Somali government?

PDW: Peacekeeping missions cannot control what their host governments do, nor do they have much influence over local politics. So, the short answer is that there is not a lot Amisom could do to stop infighting among Somalia’s political elites; the mission could only try and limit the damage. Disagreements between Somali elites slowed the building of an effective set of national security forces for many years.

Amisom was largely powerless to stop this. It led to considerable mistrust between Amisom and the Somali National Army, which, in turn, left Amisom without a reliable local security partner to help stabilise the settlements it recovered from al-Shabaab. al-Shabaab also benefited by playing off one faction against others and from the fact that Somalia’s squabbling political leaders were not focused on defeating the militants.

FA: What about your thoughts on attempts by Somali politics actors to make the operations and goals of the mission more amenable to their own priorities?

PDW: All governments that host peace operations want the peacekeepers to follow their own priorities. Amisom is no exception. The Somali federal authorities saw Amisom’s main role as a military tool to help contain and degrade al-Shabaab. They did not want a broader multidimensional mission with large police and civilian components.

Some Somali administrations have also tried to use parts of Amisom to weaken their domestic political opponents rather than al-Shabaab. Fortunately, today the relationship is better. There should be close alignment between the host government and the peacekeepers’ mandate. And in Amisom’s case, because there has never been a peace process between the Somali government and al-Shabaab, the African Union clearly took sides. This meant there was generally a very close relationship between the mission’s mandate and the Somali government’s security priorities.

FA: The new ATMIS mission which replaced Amisom has said it will focus more on building Somalia's army and taking a supporting role as Somali forces take the operational lead against al-Shabaab. Do you think the change in the goals and operational method of the new mission reflect lessons learnt or is there something more that could be focussed on so that Somalia can be ready to assume responsibility for its own security?

PDW: The new ATMIS mission is based on the right idea: that it should shift to supporting Somali-led operations and building an effective set of Somali national security forces. In the absence of a peace agreement with al-Shabaab, that is the AU’s only exit strategy from Somalia.

However, the AU mission, and the overall war, has been stuck in a military stalemate with al-Shabaab for roughly seven years. Therefore, arguably the key issue facing ATMIS is how to reconfigure its force posture so it can actively support offensive operations against al-Shabaab’s main strongholds, rather than being a largely static force stretched out across dozens of remote forward operating bases.