Thursday 21 November 2024

Freire in Somali

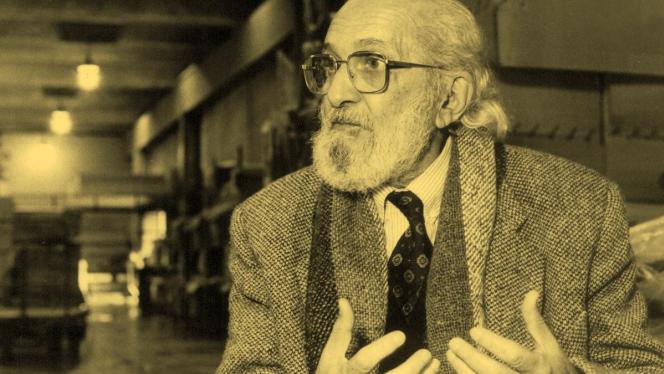

“Word is not the privilege of some few persons but the right of everyone” — Paulo Freire

Translating Paulo Freire (1921-1997), who was the pedagogue of the oppressed, into the Somali language was a significant endeavor for me, that holds profound implications for education and empowerment within the Somali context, and there is a significant relevance to the Somali people and their unique socio-cultural and historical circumstances.

One of the key concepts in Freire’s work is the idea of conscientization, or critical consciousness. This concept emphasizes the importance of individuals critically analyzing the world around them (naming the world, as Freire would rather put it) and taking action to transform oppressive structures. By translating Freire’s work into Somali, individuals in the Somali world can develop a deeper understanding of the systems that marginalize them and work towards dismantling them. This can empower communities to challenge oppressive power structures and advocate for their rights.

Language serves as the gateway to knowledge and comprehension, and it is “never nautral” as Freire emphasised. Through the translation of Pedagogy of the Oppressed—the third most quoted humanities book in the world—into Somali, I aim to bridge a linguistic divide, enabling the widespread dissemination of Freire's critical pedagogical theories. This act of translation transcends mere linguistic boundaries; it is a cultural endeavor, a praxis in the Freirian sense, involving the interpretation of Freire’s concepts in a manner that resonates with the Somali experience. Moreover, the translation of Freire’s work into Somali holds the potential to enhance cultural relevance and authenticity in education. By utilizing the Somali language and context to convey Freire's ideas, educators can render the content more accessible and relatable to students. This approach enables students to see themselves mirrored in the curriculum, fostering a sense of engagement and empowerment in the learning process.

In Freire’s seminal work, he presents a compelling manifesto advocating for the liberation of the oppressed through the transformative power of education. He vehemently argues against the traditional “banking” system of education, where students passively receive knowledge, in favor of a more interactive and engaging approach that encourages critical thinking and action. For the Somali people, who have endured decades of conflict and oppression, Freire’s message holds particular significance. Education has the potential to be a catalyst for social change and personal empowerment, offering individuals the opportunity to break free from the vicious cycles of violence and poverty that have plagued their communities. It is evident that the outdated “banking” model of education has only served in our settings to perpetuate the status quo, creating individuals who are mere puppets of the system. By embracing Freire’s vision of education as a tool for liberation, the Somali people can begin to chart a new course towards a brighter and more equitable future.

The Somali context is characterized by a tumultuous history of colonialism, civil war, and ongoing struggles for stability and peace, with religious extremism and poverty posing significant challenges. The concepts of oppression and liberation put forth by Freire hold particular relevance for the Somali people, who have long grappled with various forms of adversity. Translating his work presents an opportunity to reflect on these experiences and explore new avenues towards a more just society.

By making Pedagogy of the Oppressed accessible in Somali, educators and activists can cultivate a critical pedagogy rooted in the realities of Somali life. This can pave the way for the development of educational initiatives that are not only culturally resonant but also politically transformative, empowering students to actively engage in the rebuilding of their society.

Furthermore, translating Freire’s work into Somali can facilitate dialogue and collaboration among diverse groups in Somalia. By engaging with Freire's ideas in their own language, individuals from different backgrounds can come together to discuss and address issues of oppression in a meaningful way. This can foster a sense of solidarity and collective action among marginalized communities in the Somali peninsula.

Moreover, translating Freire’s work into Somali can contribute to the decolonization of education in Somalia. By integrating Freire’s ideas into the educational curriculum, educators can encourage critical thinking, dialogue, and introspection among students. This, in turn, can enable students to gain a deeper insight into the societal, economic, and political influences that shape their existence, empowering them to challenge oppressive systems.

One of the reasons I have undertaken the task of translating Freire is also to advocate for the democratization of educational settings, classrooms, and campuses. It is evident that our schooling system has become increasingly undemocratic, with students and even teachers facing consequences for expressing their thoughts freely.. This injustice must be rectified, and I firmly believe that delving into Freire’s work can pave the way for change, because, in the words of Freire, “if the structure does not permit dialogue, the structure must be changed.”

Paulo Freire consistently spoke out against the inherent dehumanization and alienation that occurs in oppressive environments. He believed that individuals subjected to dehumanizing processes, such as warfare, colonialism, or oppressive regimes, are at risk of losing their humanity. Following this phase, the most crucial task for these individuals is to reclaim their humanity. Freire famously stated, “Dehumanization, although a concrete historical fact, is not a given destiny but the result of an unjust order that engenders violence in the oppressors, which in turn dehumanizes the oppressed.” Therefore, I firmly believe that translating Freire’s work into Somali can provide the Somali community with a deeper understanding of the concepts of humanization and rehumanization. This will allow readers to familiarize themselves with the essence of reclaiming their humanity in the face of oppression. Because it is important to recognize the wisdom of Freire’s warning that “during the initial stage of the struggle, the oppressed, instead of striving for liberation, tend themselves to become oppressors, or ‘sub-oppressors.’” By acknowledging this, we can prevent falling into the trap of perpetuating oppression rather than working towards true liberation.

In conclusion, the translation of Pedagogy of the Oppressed (“Tacliinta Dulmanayaasha” in Somali, published in 2022, together with Fanon, Said and others) transcends mere academia; it embodies an act of liberation. It illuminates the transformative potential of education as a tool for emancipation and establishes the foundation for a pedagogy deeply connected to the realities of the Somali people. Just as Freire espoused, education is the very essence of freedom, and by embracing this philosophy in the Somali language, we unlock boundless opportunities for enlightenment, progress, and societal transformation. For this we can yearn for a world, in his own words, “that is less ugly, more beautiful, less discriminatory, more democratic, less dehumanizing, and more humane.”