Thursday 21 November 2024

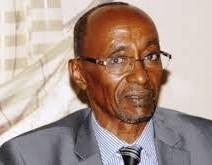

Hussein Bulhan on the colonial partition of the Horn

In 1980, shortly after the failed Ogaden War, Hussein Bulhan, an anti-colonial Somali psychiatrist and Fanon scholar, wrote one of his seminal works. In it, he explored the impact of the colonial partitioning of Somali territories along artificial, European-imposed borders on what he termed the Somali psyche. Bulhan argued that the “human-centered” Somali traditions, which had previously evolved to cope with a harsh ecological environment, were disrupted, giving way to a culture preoccupied with “death and doom.” He writes: “When at last culture and psyche were assaulted, neither could survive the erosion of the material base; the Somali lost hope, and his world became utterly disrupted.”

This paper was previously unavailable online and is presented here in full for the first time. Bulhan wrote it in the Horn of Africa journal’s 3rd volume.

Abstract: Beginning with the history of colonial partition of Somaliland, the present article explores social and individual crises in contemporary Somali society, focussing on the anguish and indignities that colonial partition imposed on the markedly homogeneous Somali nation. Dismemberment of Somaliland entailed the dismemberment of the Somali psyche, while efforts at national unity and psychic wholeness have been repeatedly frustrated. Somalis under Ethiopian rule have suffered most in this double tragedy, and many find themselves in institutions like Lazaretti Asylum in Mogadishu, a relic of colonial rule, alien, irrelevant, and dehumanised. The plight of Somalis is an integral component of the scandalous history that Europe and two zealous Ethiopian emperors unleashed upon the Horn of Africa.

Partition of Land and Psyche in Somali Society

This article explores social and individual crises in contemporary Somali society. It begins with the history of colonial partition of Somaliland. Its central thesis is that dismemberment of Somaliland entailed the dismemberment of Somali psyche. The plight of Somalis is presented as an integral component of the scandalous history that Europe and two zealous Ethiopian emperors unleashed upon the Horn of Africa. This is mainly a psycho-historical interpretation. It is neither a treatise on colonial history nor a “legal” argument on the conflict in the Horn. Indeed legalistic debates on the Somali partition have thus far obscured the massive agony in the region. Following tenets and procedures of an imposed “international” legal order, they also undermine genuine communication and reconciliation among the peoples of the Horn. The search for a just solution from alien forces that have never been just to the peoples of the Horn is truly fruitless. The article focuses on the anguish and indignities that colonial partition imposed on the markedly homogeneous Somali nation. Others in the region no doubt have also suffered many profound scars. But what torments and haunts the Somali is the dismemberment of his land and psyche. And as we shall indicate below, Somalis under Ethiopian rule have suffered most in this double tragedy. Efforts at national unity and psychic wholeness have been repeatedly frustrated. The ordinary Somali knows he has to contend with a chain of predators, within and without his society. He sees Today there are graves where thousands of refugees are hastily buried. There are also alien asylums, relics of colonial rule, serving as special graveyards where some of the living are unceremoniously dumped.

The traditional culture, a protective armor in a harsh ecology, has been undermined by colonialism. Its social nexus, values, and indigenous therapies have become dislocated while no viable alternatives are presented. Moreover, those who are entrusted with the task of leading and finding a solution, themselves products of colonial systems, know no better than to manipulate and exploit their fellow countrymen. Thus, in the current state of social crisis, sanity is left with little refuge, and madness intensifies a condition of shared unfreedom. The psychic re-constitution of the mad also becomes hardly attainable in a society itself dismembered and tormented. Yet the present confused, floundering generation must take into account its colonial past in order to chart an uncertain future and actualize dreams long deferred.

Partition of Land and Psyches

Before colonialism, the Somalis faced one primary enemy — namely, a harsh ecology. Elaborate social nexus and human-centered outlook constituted a cultural bulwark, a collective defense, against this barren ecology But when Europe unleashed upon the world that historic avarice for colonies, Somalis fell victim in a way little appreciated. The colonial scramble and subsequent colonial rule introduced into Somali life a havoc of catastrophic proportions. The cultural bulwark gradually weakened and people found themselves defenceless against disasters first from without, later from within. Thus any analysis of the contemporary crisis in the Somali society must take into account colonialism in Somali history.

During the late 19th and 20th centuries Somaliland became an arena for colonial scramble. Four expanding empires had their own designs on Somalis and their land. These contending powers were Britain, France, Italy, and the burgeoning kingdom of Ethiopia which was determined to share the loot. Its emperor, Menelik II, an astute and ambitious power-broker who, having decimated local rivals, set out to establish an expansive empire of his own. The European avarice for colonies found a ready and willing accomplice in the intrigues and ruthlessness of Menelik II. Somaliland was subsequently partitioned and the homogeneous Somali nation was subjected to all forms of colonial atrocities.

Britian's initial interest in Somaliland centered on a desire to secure the flow of trade from the hinterland which supplied fresh meat to its garrison in Aden, en route to India. From 1884 to 1889, Britain concluded several treaties on trade and protection with various Somali elders. Somali elders entered into these treaties because of their alarm at the many forays and raids that the better-armed Ethiopian expansionists were making into their communities. Menelik II was already reaping the benefits of that historic ploy: “Ethiopia is a Christian island in a sea of heathens.” He gained European munitions and sympathy by this ploy.

The precipitous withdrawal of the Egyptians from the coast led Britain to establish a Somaliland Protectorate in 1887. The Anglo-Somali treaties which culminated in establishing the Protectorate were, in the view of Somali elders, contractual alliances much like those concluded in traditional societies. The preambles of these treaties left no ambiguity for their purpose. They were explicitly concluded “for the maintenance of our independence, the preservation of order, and other good and sufficient reasons.” Britain also pledged that no portion of Somaliland was ever to be ceded, sold, or mortgaged to a third party. Similar treaties were also signed with France and Italy. Somali elders entered into these treaties in good faith and for self-preservation. But the treaties soon proved to be an alliance with Lucifer himself.

Britain gradually gained ascendancy as a colonial power in the Horn. The three European powers subsequently concluded initial agreements on spheres of influence and boundary demarcation. The Anglo-French Treaty of 1887 fixed the present boundary between Somalia and the Republic of Djibouti. From 1889 to 1925, a series of Anglo-Italian treaties divided and re-divided colonial spoils in Somaliland. Somalis were neither informed nor consulted on the partition of their land. True to colonial practice of thingification, their consent became as irrelevant as that of plants and animals in the land. This pattern was to give a fundamental twist to the history of the Horn. Indeed vestiges of that thingification are to this day obvious in the very practice of some leaders in the Horn who inherited the colonial machine. Today as then, the consent of the people remains as irrelevant as that of plants and animals in the land.

Meanwhile, as Europeans engaged in secret negotiations to share the spoils, the subterfuges of Menelik II and heavy infusion of European munition to his army, were catapulting Ethiopia into a junior partner in the partition of Somaliland. The Brussels General Act of 1890 exempted Ethiopia from the prohibition of firearms to all Africans. This was calculated to hasten colonization and reduce African resistance. The provision of munition to Menelik's army of ambition and the simultaneous “pacification” of other nationalities further destabilised the area. Also European concerns about the Mahdist insurrection in the Sudan and the Italian defeat at Adowa in 1896 bolstered Ethiopia into a favoured partner in the colonial scramble. Menelik had by then unabashedly pronounced his expansionist ambition in his now famous statement: “If powers at a distance come forward to partition Africa between them, I do not intend to be an indifferent spectator.” By 1897, within a few days of each other, representatives of Britain, France and Italy, struck separate deals with Menelik II.

In the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897, Britain ceded on paper a significant portion of Somaliland to Ethiopia. The secret treaty was not published and the boundary was not marked until the early 1930’s. Somalis came to know of the treaty mainly in 1954 when the “Haud” was eventually transferred to Ethiopian authorities. The Franco-Ethiopia Treaty of 1897 also ceded a considerable part of French Somaliland. The Italo-Ethiopia-Agreements of 1897 attempted to define the boundary between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland. A second agreement in 1908 attempted to define a precise boundary but to no avail. In the end, after decades of colonial bayonets and barter, Somaliland was effectively partitioned into five colonies: British Somaliland, French Somaliland with a substantial Afar population, Italian Somaliland, the NFD (Kenya), Western Somaliland (the so-called Ogaden) under Ethiopian rule.

Somaliland was thus dismembered and so was Somali society. If colonization and partition were consummated without the people's consent, the actualization of both were intensely resisted by all means at hand. The early and heroic resistance of Sayyid Mohamed Abdulle Hassan kept the British at bay for twenty years (1899 1920). His movement was later crushed with air bombardments. This event marked the first time airplanes were used to subjugate a colonized people. Somalis were at once faced with a confluence of formidable and better-armed foes. The active and long resistance of the Sayyid gave way to sporadic and passive resistance.

When partition of the land could not be avoided, salvaging the integrity of Somali culture and psyche became the ultimate hope. Partition and colonization inevitably dislocated the mode of production and free movement of the nomadic Somali. When at last culture and psyche were assaulted, since neither could survive the erosion of the material base, the Somali lost hope and his world became utterly disrupted. The old, human-centered culture gradually gave way to an obsession with death and doom. Earlier generations of Somalis regarded the alien assault and partition not only an end of an era but a proof that the last days of the world were imminent. Farah Nur, the famous poet and leader who died in the early 1930’s, had captured the emerging Somali mood in the following words:

The British, the Ethiopians, and the Italians

are squabbling,

The country is snatched and divided by

whosoever is stronger,

The country is sold piece by piece

without our knowledge,

And for me, all this is the teeth

of the last days of the world.

For a short period, World War II brought virtually all Somalis under a single colonial administra-tion. The British Military Administration took control of Somaliland, including those portions under Italian and Ethiopian rule. The BMA was established in 1941 and ended by the late 1940’s. During 1946, Ernest Bevin, the British Foreign Secretary, articulated the injustice of the partition. At last, it seemed, the plight and right of Somalis were to be recognized. Bevin proposed a united Somaliland under one colonial power:

... In all innocence, therefore, we propose that British Somaliland, Italian Somaliland, and the adjacent part of Ethiopia, if Ethiopian agreed, should be lumped together as a trust territory, so that the nomads should lead their frugal existence with the least possible hinderance and there might be a chance of a decent economic life, as understood in that territory.

Bevin added: “All I wanted to do is to give those poor nomads a chance to live ... It is to nobody’s interest to stop the poor people and cattle their getting a decent living.” This plea, if at all sincere, was indeed unacceptable to imperial powers. The British Government itself and of course Ethiopia rejected the proposal. Representatives of the United States, the USSR, and France also took a cynical view of Bevin’s proposal. The flicker of hope and possibility of free movement were thus once again drawn by conflicting ambitions of imperial hegemony. Thus Somaliland was re-partitioned and the fate of its people sealed again by dint of superior arms. The material foundation of his life dislocated, the Somali once again fell prey to new indignities. The avalanche of torment and deception that colonization and partition entailed for Somalis cannot be fully recounted. We will provide some examples, however.

From the very beginning, each colonial power subjugated Somalis according to its peculiar perversions. When the British took initial control of their Somali colony, they embarked on punitive raids further inland where resistance interfered with trade caravans serving their garrisons in Berbera and Aden. The British fanned clan conflicts and conducted expeditionary raids in the country. Elders and religious leaders were bribed and appointed to nominal positions of authority to forestall national resistance. This began to undermine the old trust and respect for traditional leaders. Moreover, nomads from the interior were initially prohibited from coming to urban centers until they brought with them two boulders needed for building colonial offices and mansions. They were, in addition, required to leave their arms in a police station. If they were caught fighting, their arms would temporarily be confiscated and were then forced to dig a grave. The British knack for 'divide and conquer' found ruthless application in interpersonal conflict once the grave was dug. The grave dug “to the satisfaction of the police, their arms were returned and they were urged to resume their fight on the understanding that the victor would bury his adversary.” What is more, the result was then widely announced by the town announcer!

The indignities and compulsory labor ordinance of Italian fascism is too well-known. What is often little appreciated is the boiler that Ethiopia has been for Western Somalia. The costly taxes, the constant raids, the pillage and rape the people suffered are too many to enumerate. I will cite one incident I myself witnessed as a child growing up under the feudal fist of Ethiopia. An Ethiopian tax collector was killed in the environs of Jigjiga, my home town. The killer was neither known nor apprehended. But for revenge and mass intimidation, the Ethiopian authorities decided to execute ten innocent Somali men. On the day of the execution, every Somali in town — child or adult - was forced to watch the terrifying spectacle. Each victim was made to stand on a pick-up truck with hands tied behind his back. A noose of rope, suspended from a horizontal pole, was then placed around each victim. After a speech of intimidation and warnings to disgusted observers, the driver was ordered to quickly move the truck leaving behind a writhing humanity in mid-air, gasping and sometimes urinating in death.

I can never forget the plea of one bearded-elder among the victims. With a remarkable calm and dignity, he uttered one and only one request: “If my son and I must die, please let me go first and in a different pole.” That plea was never granted, and the grisly execution proceeded as planned. When each pair was hanged, we were then herded to the next location. On three separate occasions, the rope broke, unable to withstand the weight of victims. Each time, the victim was picked up, put on the truck, and hanged again. The ten men were left hanging for several days for all in the city to see. Nightmares and repressed rage subsequently became part of our colonial heritage. When I later came to the United States, I understood the terror and rage Black America had experienced during the long history of lynching.

The Revolution of Expectations

World War Il marked a watershed in the history of colonial peoples. A resurgence of national resistance also swept all over Somaliland. By the late fifties, a new day seemed to dawn for the wretched of the Horn. Independence for portions of Somaliland appeared close at hand. The upsurge of nationalism gained a distinct tempo and intensity. The former Italian colony was scheduled to gain its independence in 1960. Developments in one of the British colony, the so-called Protectorate, were quite promising. Hopeful prospects also seemed afoot in the French colony and the NFD. Somalis under Ethiopian rule, brutally tormented and humiliated, began to sense new possibilities in the horizon as they vicariously relished news of victory in Mogadishu and Hargeisa. Radios were almost banned and certain stations intentionally jammed.

But they huddled around, glued to transistor radios in secrecy. On July 1, 1960, the former Italian and British colonies spontaneously united to form the new, independent Somali Republic. Aspiration and hope re-kindled everywhere and mutilated psyches, burdened by decades of indignities, sensed that the hour of national and psychic reconstitution was indeed imminent.

But the fact of dismemberment, whether of land or psyches, soon proved far more stubborn. Unity became ever elusive. The birth of the new state was but a miscarriage. Anticipated pregnancy for others proved only sheer fantasy. Disillusionment soon set in the new Republic. Colonial structures remained very much intact. The captive intelligentsia soon revealed its bankruptcy. The long-cherished dreams of liberation in the remaining three colonies were no longer tenable. The relapse back to familiar despair and dismembered psyche was once again quite evident.

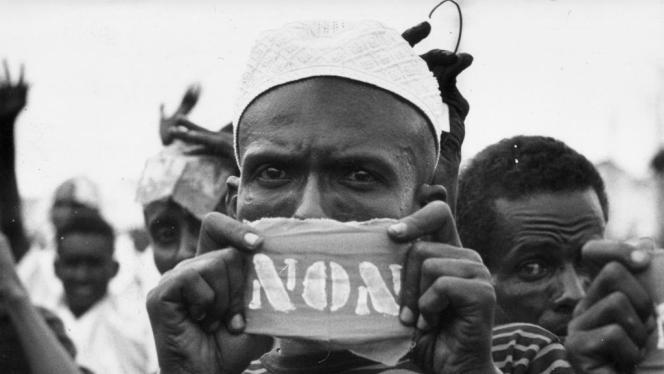

In the French colony, the Gaulist referendum of 1958 ostensibly offered a choice between independence and remaining an oversea territory of France.

The result seemed almost inevitable. Mohamud Harbi, then the second man to the French Governor, established a formidable coalition with a segment of the Afar and made no bones about his nationalist platform. He favored independence and unity with Somalia. The referendum was subsequently rigged and, in the ensuing confusion, the French authorities dissolved the assembly in which Harbi was the Vice-President. Harbi was soon forced to flee to Egypt and later to the Somali Republic. In October 1960, he mysteriously died while on a visit to China and Eastern Europe.

Somalis in the NFD meanwhile agitated for UN plebiscite to determine the wish of the people. The British instead sent a commission in 1962 and found that an overwhelming majority elected to unite with the Somali Republic. The results were declared and Somalis everywhere had a reason to celebrate once again. But then came the cruel let-down, as it did so many times before. Britain unilaterally decided to renege its pledge to abide by the results of the plebiscite. It had far greater interests in Kenya (one of its prized colonies) than to champion the cause of justice. The deception and debacle in the NFD had their precedents in how Britain previously handled the Anglo-Somali Treaties and then repeatedly delivered Somalis to Ethiopian subjugation. The neocolonial dependence of Kenya could thereby be insured since British aid would be needed to subdue the enraged and cheated populace of the NFD. Hence another stage was set for hostility and occasional bloodshed between two African neighbors that might otherwise have found realistic grounds for peaceful co-existence, if not needed harnessing of mutual resources. Today Kenya and Ethiopia have a military pact against Somalia - a shared animosity to Somalia and, more fundamentally, an opposition to Somali unity have cemented a marriage of convenience. Kenya today recognizes NFD Somalis as Kenyans and allows them a significant measure of rights as citizens.

As for Western Somalis, their lot had become more dismal under the skillful subterfuges of the late Haile Selassie. The levying of exorbitant taxes, the sacking of communities unable to pay them, the frequent plunder of nomads eking modest existence, the execution of life-imprisonment of suspected nationalists — all these continued to torment Somalis without respite. The feudal fist and blanket of suppression were mercilessly pounding and suffocating the populace. American weaponry and undisguised uniforms were everywhere. By the early 1960’s, Haile Selassie enjoyed a political bonanza from years of propaganda unleashed in UN corridors and international platforms. The history of accomplice to colonial rule in Africa was paying its returns both in kind and arms. The fascist adventure in Ethiopia had given the ruthless emperor all pretensions of a liberator. Blacks in the Diaspora, submerged under debilitating oppression, needed a hero and dreams of deliverance in the Promised Land. For some of them, particularly in Jamaica, Haile Selassie was not only a hero but indeed a god.

But the oppressed of the Horn knew that mythical Ethiopia was one thing, historical Ethiopia quite another.

By early 1960, Haile Selassie was hailed as the father of African Unity. Only the oppressed nationalities of Ethiopia could chuckle at the absurdity of this title. It is as if a wolf was honored as the guardian of lambs. Nkrumah's emphasis on a people's right of self-determination also lost favor under the machinations of the emperor. The Organization of African Unity soon accepted Addis Abeba, Ethiopia's capital, as its home-base. It then adopted in its charter that the colonial borders were sacrosanct. This meant that the ruthless oppression of Western Somalis is sacrosanct and internationally condoned.

The question no longer entailed a struggle against specific, though formidable, oppressors. The tormentors of the Western Somalis became more global, their plight more intractable. Besides a dubed international opinion and a chain of colonial accomplice had to be confronted. Then the long-awaited occasion came — the empire began to crumble of its own internal rot. Western Somalis hastened to reclaim and liberate their land. Other Somalis across the border gave to the effort all they had - blood and brawn. But the victory and emerging psychic re-constitution was short-lived.

The Soviet Union and Cuba, previously masquerading as champions of justice, interceded on behalf of Ethiopia with sophisticated arms never before seen in the Horn. They subsequently restored the empire and sealed the lid on the Ethiopian boiler.

Today, there are almost two million refugees in Somalia. They have been forced out of their land with systematic pillage, napalm, and poisoning of their wells. A UN document (1979) reported that camp population was increasing at the rate of 1,500 per day during the last quarter of 1979. A total of 474,000 were then in camps and the rest temporarily settled among the local population. Children comprised 61 percent and women, 30 percent. A detailed report by the Center for Disease Control indicated that by August 1980, there were 28 refugee camps in Somalia. Many of the camps contained an estimated population of 40,000-50,000 each. The problems of over-crowding, sanitation, malnutrition, and mortality in these camps are appalling. Most affected are of course children, lactating mothers, and the elderly. The ACD survey reported that child mortality in certain camps was nearly 47 percent and over 60 percent of diagnosed camp-residents suffered from diarrhoeal diseases, malnutrition, and respiratory infections. The massive agony of two million refugees also aggravates the ecological, economic and health conditions of Somalia itself. The net effect of these developments on the Horn are yet to be assayed. But the Somali is convinced of one thing: this campaign of terror and dislocation is nothing short of a genocide. The recognition of this fact fills the Somali with rage and profoundly affects his psychology.

Crisis in Contemporary Society

The avarice for colonies that Europe unleashed on the world has today left behind many victims than villains. Wherever it intruded, its legacy of destruction and dehumanization is evident. The greed of Europe for having more has ossified many into being less. Social institutions of oppression have since been elaborated and the victim-predator dynamic has everywhere sipped in the collective unconsciousness. The harrowing account of victims can be gleaned from the face of the Black American stranded in a vandalized project, the stooped Senegalese sweeping the streets of Paris, the indignance of the Jamaican abused by immigration officers at London's Heathrow Airport, and the intense dilemmas of a South African mine-worker whose very labor intensifies his own oppression. The human wreckage is strewn everywhere.

But what is little appreciated is the havoc and indignity that colonialism had heaped on the Somali. The question for him has never been identity-confusion or inferiority complex. If that were so, many in the world would perhaps sympathize with him. The Somali would in that case sing a tune familiar to victims elsewhere. On the contrary, his problem is asserting who he is and piecing together a scattered national identity. A long chain of formidable foes have been responsible for the Somali predicament. They control the way information is disseminated in the world, are better armed, and control the “international” legal order. Thus the Somali’s efforts at national unity and psychic reconstitution have conveniently been labelled as “expansionist” and “irredentist”.

Meanwhile, many a Somali family is torn asunder by artificial national borders — parents in Western Somalia, a brother in Djibouti, a sister in Somalia, and an uncle in the NFD. The common ravages of war and famine, the many frustrated hopes of national and psychic wholeness, the eternal conflicts with neighbors, a dubed international community programmed to misunderstand the Somali predicament, the abuses and manipulations of a captive intelligenstia, the two million refugees forced out of their land — all these weigh heavily on Somali psyche and contemporary society.

These disasters, first from without and later from within, have been unfolding for a long time. Because of them, contemporary Somali society has been transformed into a veritable inferno. The transformation is most fundamental, not mere surface alterations. The great divide between life and death, as between sanity and madness, has become too blurred for those entrapped in the dismembered realities of the Somali nation. Life for the majority is but the beginning of that dreaded end: an ever present death itself. What is celebrated is that one has merely survived, temporarily for sure. Sanity too is left only with a narrow, tenuous refuge in a world strewn with prohibitions, frustrated hopes, and frequent loss of loved ones. There is a madness which ostensibly afflicts a few, but insidiously engulfs the majority.

The traditional culture which served as a defensive bulwark in a harsh ecology has been gradually disintegrating. Its social nexus and outlook, adaptive under different conditions, have now been degraded to lethal instruments of political and social manipulation. This degeneration is best illustrated by the resurgence of clan politics in contemporary Somali society. The old tradition of sharing on the basis of common bond and cultural norms is also supplanted by personal greed of owning more by all means. The word which once was embued with human values is now replaced by monetary power. The Somali shilling — better still, the American dollar in illicit markets — has become the measure of self-worth and social status. Today one is worth what one privately owns, not what one contributes to the common good. Yet the economics of scarcity breeds only more frustrations for the majority. A psychology of predators thus combines with limitation of resources. The raw justice which earlier generations repudiated is now ossified into a system of injustice.

The captive intelligentsia on whom the ordinary Somali has entrusted the unenviable task of ameliorating his predicament are thus far incapable of meeting the challenge. They are busy in internecine conflicts, appointing relatives to high positions, manipulating everyone for an advantage, and wallowing in abuses they inherited from colonialism. The rulers find too burdensome the very governance of even the sane. They are like captives of a sinking ship where simple survival, their own survival, becomes the measure of success. Higher ideals of altruism, humanitarian gesture to the weak, and concern for the common good die hard under these conditions. The will to survive, by whatever means, has taken precedence over all other priorities. This is true in national policy as individual psychology. Those who rule as well as the ruled, both guided by that desperate impulse, show neither the will nor wherewithal to transform themselves and society. Members of the captive intelligentsia who seek to elaborate a new society on the ashes of the present are too few and unorganized. They are quickly swept away by the living inertia of the colonial past.

Somalis who ostensibly suffer from madness are today dumped in institutions like Lazaretti Asylum which was built by Italian colonizers in Mogadishu. Lazaretti is indeed medieval and alien. The sterile, colonial structure, designed for custody, has no sanitary facilities. It is over-crowded with epileptics, the retarded, and the psychotic and occupies part of a large compound that also houses a hospital for TB and other infectious diseases. The whole compound is unkempt and dilapidated. When we visited it in the summer of 1979, we saw some of the patients were shackled, some incarcerated in locked rooms, a few walked around naked, and most showed poor nutritional status. There were altogether 225 patients and 17 staff members. The majority of the staff had little training, neither in Western nor indigenous psychiatry. There was only one physician and Electroconvulsive therapy was used in unmodified form. The staff did not choose to work there and felt resentment at having been forced by the Ministry of Health. Morale was poor. There was a marked deterioration of staff-patient ratio at various times of the day. There were usually twelve staff members during the day, two in the evening and only one at night. The patients were cut off from family and society. A significant number of these patients were from Western Somalia.

When I first visited Lazaretti in 1969, I was surprised to find a high proportion of Western Somalis incarcerated in it. For instance, one day I was walking in the over-crowded compound when one naked and emaciated patient rushed to embrace me with: “Allah! Waa Hussein!” I later recognized him. He was from Jigjiga, my home-town. On the same day, the police brought in a young man who attempted suicide in the city. He too, I found out, was from Western Somalia. Forced out from his homeland and unemployed in Somalia, this proud nomad could not get himself to beg others for his livelihood. He told me: “... You can't get even the most menial job in this city without the help of relatives. But I've no relatives here. All I'm left with is a choice between begging and death. At my age and youth, I would rather die then beg.”

Ten years later (1979) I found that the proportion of Western Somalis and victims of war-neurosis had markedly increased. Shattered personalities were appallingly everywhere. None can illustrate the anguish of Western Somalis better than one patient from Dire Dawa, an important city under Ethiopian rule. He was an employee of the Ethiopian Airlines. But because he was a Somali, he became a target of relentless suspicion, surveillence, and abuse by his Ethiopian colleagues. Then came the long-awaited chance to escape his tormentors. He joined a flight bound for India. On its stop at Jiddah, Saudi Arabia, he left the plane on a contrived errand, never to return to his tormentors. The Saudi police apprehended him and decided to send him back to Ethiopia. The prospect of a forced return to Ethiopia entailed certain execution or a long imprisonment. He escaped once again, managed to get a Somali passport, and arrived in Mogadishu.

A long period of unemployment and disillusionment in Somalia was followed with a series of nervous breakdowns. He was in and out of Lazaretti where he was given numerous electro-shocks but with little avail. When we saw him in 1979, he was all-bones and suffering from a severe depression. The sanitary and nutritional condition of his incarceration left him with a serious infection in the mouth and vital organs. Appropriate medications for either his psychiatric condition or infections could not be found in Somalia. Incapacitated and unable to talk, he answered our inquiries in brief, written re-sponses. He asked us persistently: “When am I dying?” His loving and pained brother intimated to me: “How can we deal with this predicament of neither life nor death? His wife, children — all of us — are emotionally exhausted in a way worse than grief itself.”

If this family is a veritable victim to Ethiopian torment, the patients of Lazaretti represent the cummulative anguish of a nation dismembered, manipulated, and exploited. They also demonstrate the effects of a dislocated culture and of its indigenous therapies. As Western Somalis escape from Ethiopian harassment and pillage, they come to a welcoming but exhausted country across the border. Some of them find employment or relatives with means. Most find themselves very much stranded, hungry, and without shelter. They become refugees without the consoling recognition or support of the international community. Those who cannot bear the agony of their predicament end up in asylums like Lazaretti and are thereby subjected to electroshock and medieval indignities.

Clearly, the colonial rulers did not only dismember land and psyches. They also introduced medieval asylums and one brutal technique: Elec-troconvulsive therapy (ECT). In its standard form, ECT involves passing an electrical current of approximately 160 volts on each side of the patient's head for 1-2 seconds. The patient immediately loses consciousness and shows first tonic (extensor) and then a lengthy series of clonic (contractile) seizures of the muscle. In the absence of muscle-relaxant premedication, the initial seizures are so violent as to fracture bones and vertebrae. The shocked patient gradually gains consciousness but remains dazed and confused for several hours. Memory impairment often remains for months. Application of about a dozen shocks to each patient has been common. The technique is now rarely used in the United States and Europe.

By imposing asylums and ECT, the colonizers utilized techniques of social control and dehumanization which had proven effective in their own countries. Just as the land was arbitrarily dismembered without the people’s consent, ECT is to this day indiscriminately administered on Somali patients without their consent. If use of ECT and existence of asylums are the crudest relic of colonialism in Somalia, more subtle and insidious vestiges are found in the psyche and social behaviors of those who rule contemporary society. Rule without consent and citizenship without rights are still facts of life for the wretched of the Horn. His egalitarian tradition, dislocated by colonial rule, is today replaced with a “rule of the family”. Certain disgruntled and misguided members of the captive intelligentsia reacted to this by recently opting to collaborate with Ethiopia. Their motivation is to displace one rule of the family by another. Ironically, the military wing of this clique calls itself: The Somali Salvation Army!

In short, the dismemberment of Somaliland entailed dismemberment of Somali psyche. The traditional modes of explaining and treating madness are fast becoming ineffectual because the culture on which they are founded is rending. The individual is today easily traumatized. There is no social anchor, no guiding or binding principles, nor purpose beyond a readiness to skin others before being skinned. Today the Somali looks around or delves into history and finds only a chain of predators. Pledges of redress, repeatedly frustrated by colonial rulers, have given a cynical outlook. Promises of national re-construction by Somali leaders give him reason to be hyper-alert. Such promises have, time and again, proven to be new ploys for manipulation.

The history of torment and disappointments are today manifesting their cumulative effect. Refu-gees, famine, and exploitation are rampant. A culture of despair seems to be emerging. The two million refugees from Western Somalia only exacerbate the massive hemorrhage. One hopes that the tested resilience of the ordinary Somali will soon find a committed cadre of Somalis who will confront the avalanche of indignities by creating new solutions to old problems. It is never too late. The first question such a cadre will face is of course this: How can they convince the ordinary Somali that they too are not disguised, new predators in a long history of predators?

The choice is also clear for the peoples of the Horn. Either they will sink together in the quagmire of destruction, one nation pitted against another, or together they will decide to forge a new history and set afoot a new humanity in the Horn. The first choice maintains the present conditions of self destruction. The legacy which Europe and two zealous emperors have imposed on all will continue to sow discord and despair. Servants to that legacy will hasten the superpowers to compete in the Horn. Children will remain to be socialized with ethnic stereotypes and ossified fears. Soldiers will continue to die in vain, thousands orphaned, and loved ones will perish in war, famine, and refugee camps. Representatives of local tyrants will still fan hatred and, at UN corridors and platforms, parrot each other litany of grievances on behalf of a people they themselves mercilessly torment.

The second and more difficult choice means unloading the historical and psychological baggage which today weighs heavily on their psyches, in dreams and daily living. It requires a new vision, cracking old fears, and a willingness to empathize the agony of the other to discover the shared vic-timization. Appeals to reason are certainly not sufficient in themselves. What is required are new alliances and critical stance toward those who have an interest in maintaining the cycle of destruction in the Horn. Now the superpowers are poised for in tense conflict in the Horn. Military bases are being offered, left and right, for personal advantages and without consent of the people. Such developments only emphasize the second choice - namely, true decolonization of society and psyches in the Horn — remains a project of the future.