Thursday 21 November 2024

The serf emancipation movement in 1940s Eritrea

The serf emancipation movement in the western lowlands of Italian Eritrea fostered a new political consciousness in the colony that would eventually contribute to Eritrea’s liberation and transform the Horn of Africa

Following World War II, the Four Power Commission (FPC), consisting of Great Britain, the USA, France, and Russia, was tasked with investigating the former Italian colonies of Eritrea, Somalia, and Libya in November 1947. As part of its peace treaty with the victors of WWII, Italy committed to renouncing “all right and title to the Italian territorial possessions in Africa”. However, Rome argued that the colonies should be returned, asserting that the wishes of the inhabitants, whom the Italian government believed were sympathetic to its continued presence, should be taken into consideration. That made an investigation necessary. The three former colonies had a combined total of 750,000 square miles, much of which was desert and had a population of approximately three million.

Eritrea was the first country the commission visited. General Frank Stafford, a member of the commission, later recalled in a speech at Chatham House how he approached the task. He mentioned that each village and tribe was advised to select spokespeople, enabling a broad survey of people’s views. This approach was complemented by “surprise visits” to villages to ensure nothing was overlooked or manipulated by local power brokers, as well as by specialised committees to gather social and economic data.

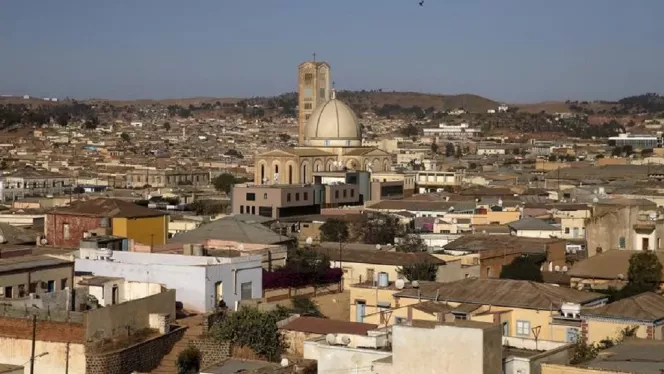

Their visit lasted from 23 November to 14 December 1947. Stafford noted that people in the region held quite polarised and irreconcilable views. The small community of Italian settlers in Asmara favoured a return to direct Italian rule, as did some of the Danakil (ethnic Afar) around the port town of Assab, which he described as “strange.” Many of the Christians in the territory, particularly on the plateau, wanted union with Ethiopia, while the inhabitants of the Muslim lowlands in the west preferred an independent state. “No one who was interrogated suggested that Eritrea should be split up,” he said, but at that point, there was “very little evidence of the growth of Eritrean nationhood.” This article aims to trace the emergence of the Eritrean independence movement to the Tigre serf revolts in the western lowlands of Eritrea.

Historical background

Eritrea, like many African countries, was a colonial creation. The interesting difference is that its fate was determined by a conspiracy between two empires. When Menelik assumed the Ethiopian throne in 1889 he promptly signed a series of treaties with Italy, among which greenlighted Italy’s expansion in today’s Eritrea. The boundaries of the Eritrean state later began to take shape through agreements with Anglo-Egyptian Sudan to the west, with France’s Djiboutian possession in the south-east and vast Ethiopian frontier. Redie Bereketeab writes: “It was at this time, in the objective sense, that the foundation of the Eritrean nation was established.”

In 1890, Italy amalgamated various sultanates and kingdoms into a single entity. As a result, Eritrea today is ethnically, culturally, and religiously diverse. The serf-emancipation movement primarily involved the Tigre-speaking people, who currently form about 35% of the population. The Tigre are not an ethnic group in the strict sense, but rather a large linguistic community concentrated in the western lowlands of Eritrea and south-eastern Sudan. Many different tribes use the language, but often identify by tribe rather than as a group themselves.

Tigrait (the name given to the language by its speakers), often referred to as Tigre, is closely related to the ancient Geez language, which is currently the liturgical language of the Orthodox Church in the Horn of Africa. It is spoken in both Eritrea and eastern Sudan. Geez is closely related to the old Sabean language of Yemen, known as ‘Al Masned’. Tigre is often confused with Tigray, the northern region of Ethiopia, but it is distinct from it.

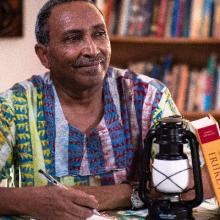

In Tigrait, Tigre refers to a serf or an Arab (used as a derogatory term). According to Enno Littmann, who extensively researched the language, in 1907, people using it as a mother tongue within Italian possessions were more numerous than any other linguistic community. The author had written three volumes on Tigrait literature.

The Tigre are overwhelmingly Muslim and like many other Muslims in Eritrea opposed union with Ethiopia. It would be this group that would form the basis for the initial Muslim movement and the independence movement later. In his Short History of Eritrea, Stephen Hemsley Longrigg, the military governor of Eritrea from 1942 to 1944 observed: “Muslim tribesmen outside the towns, who form half the population of Eritrea and occupy nine-tenths of its soil, would be generally and probably strongly opposed to such union [with Ethiopia], although it is never admitted by irredentist spokesmen.”

Gerald Kennedy Trevaskis, a British officer who served in Eritrea and author of the book, Eritrea: A colony in Transition wrote: “No significant Moslem movement could develop without the Tigray tribes, who accounted for three-fifths of Eritrea’s 520,000 Moslems.”

The Tigre people’s plight

It was in Eritrea’s western lowlands that “actual feudal socio-political structures existed,” writes Redie Bereketeab, in Eritrea: The Making of a Nation. This view was gathered by scholars who visited or studied the region because “serfdom was widely practised, particularly among the Beni Amer, Tigre and Belain”, he continues. The relationship was meant to be based on an agreement that lords would protect serfs, who in turn would maintain their obligations to them.

The noble-serf relationship was introduced in the Sahel region by the Beit Asgede, Tigrinya-speaking Orthodox Christians from Akle Guzai in the highland provinces further east. The Beit Asgede subjugated the Muslim pastoralists, but ended up interestingly adopting language, religion, and pastoral lifestyle of the conquered.

The ruling class, known as the Shumagelle, maintained their subjects in a state of bonded labour. This stratified society concentrated wealth, privilege, and prestige in one group at the expense of all others. Serfs were expected to plough their own land to feed their noblemen, collect firewood for them, and supply them with animals to carry their belongings. When marrying off their daughters to nobles, serfs also had to provide presents or risk voiding the marriage. The system was worst in the northern highlands and plains where the Beit Asgede nobility ruled, and where the revolt against the aristocratic class began.

The noble classes were not exclusively Christian. The Beni Amer, a sprawling conglomerate of different clans and tribes, also had a serf class, which some scholars believe was influenced by the practices of the Beit Asgede. The Beni Amer are the largest Tigre-speaking group and exist within a broadly hierarchical structure, divided according to different tribes. The aristocratic class was called the Nabtab, and the serfs were called the Tigre. There were further divisions of status within the Nabtab, with the highest rank held by the supreme chief, known as the Diglal. The Diglal’s rank was symbolised by a sword of honour and a distinctive three-horned headdress called a “taghia,” made of red velvet, fringed with gold, and stuffed with cotton. He is unique in Western Eritrea and Eastern Sudan for receiving this taghia from the Funj Sultanate of Sennar in Sudan.

Under this system, serfs were relatively better off than slaves as they weren’t bought or sold as property but had to work for the lords without pay. There was a degree of cooperation but the essential component of the relationship is what Redie Bereketeab called “coercive domination”. They paid taxes to plough land and owned livestock but had numerous obligations to the nobility. They enjoyed a degree of autonomy, but the divisions in society were strictly maintained. Intermarriage was forbidden for example.

The role of Italian rule

During Italian rule, the Italians used the nobility to help the country and collect taxes. The Italians reduced taxes paid by the serfs, but it wasn't enough to alleviate their burden. Reports of resistance against the nobles date back to the 1920s and 1930s. A large group of Tigres submitted a statement to Commissioner Vittorio Focardi, expressing relative relief that under Italian administration, their nobles had limited their demands and ceased taking liberties with their wives, a practice previously common.

A powerful emancipatory movement developed among the subject classes during the fifty years of Italian rule. Although disorganised and sporadic, this movement won certain liberties for the serfs. Crucial in this endeavour was the emergence of government schools which weakened the link between serfs and their Shumagelle lords and new forms of work in a modernising economy which allowed serfs to find new ways to make a living. During the transition from Italian to British colonial rule, Tigre serfs increasingly challenged their subordinate status against local landlords.

The British Military Administration (BMA)

Despite the British Military Administration’s (BMA) initial success in holding a public assembly for Shumagelle and Tigre representatives in Keren in June 1943 and relative liberalising of the political space, concerns arose about the uncompromising stance of influential Tigre activists, particularly Mohamed Hamid Tahgé. Tahgé, a Tigre leader within the ʿAd Takles clan, refused to pay any wheat to the Bet Asgede nobles, stating he would “rather die than allow a single rubaiya of dura [wheat] to be paid over to the Bet Asgede,” setting a precedent within the Tigre movement.

In 1943, another significant event occurred when Hamid Shintoob, a serf from the small tribe of Rigbat, ploughed his land without paying the ploughing tax. When his noble master attempted to stop him, Hamid injured him, leading to the noble's death. Hamid’s refusal to pay double blood money (because he killed a nobleman), supported by Ibrahim Sultan, sparked widespread resistance among the Tigre, who stopped paying various taxes, challenging the British administration.

The serf movement also opposed the Nabtab bandits in Eritrea, led by Ali Buntaz or Ali Shawish, Idris Ali Bekit, and Ali Bekit Omer, accusing them of inciting war between the Beni Amer and the Hadendawa in Eastern Sudan from 1942 to 1945. This conflict arose over grazing areas claimed by the Hadendawa, with the serfs siding with the Hadendawa. Many Hadendawa may not be aware that the legacy of these conflicts influenced inter-ethnic clashes targeting the Beni Amer after the fall of Omar al-Bashir in 2019.

Four Powers Commission

Representatives of the Tigre in Eritrea wrote a 17-page well-referenced letter to the Four Powers Commission in which they laid out their grievances about their position in Eritrea and made demands about how their situation could be remedied. “We represent almost the entire Moslem population of the western provinces of Eritrea, that is about 95% of the population,” the letter said, adding: “In spite of this we have no right to hold political posts, nor do we enjoy equality with the so-called noble class, known under the name of ‘Thanit’”.

The Tigre leaders complained that they were forced by the Thanit to plough their own land in order to feed their noblemen, collect fire for them and supply them with animals to help them carry their belongings. When they married their daughters to them they also had to provide presents, or risk voiding the marriage.

Formation of the Muslim League

The serf movement had significant impacts in Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan. Disempowered nobles sided with the Unionist Party, which promised to restore their privileges and merge Eritrea with Ethiopia. The Eritrean Muslim League, Eritrea’s first nationalist political party, emerged from this struggle on 3 December 1946. It rejected unity with Ethiopia or partition and advocated for Eritrean independence. Ibrahim Sultan, the party’s Secretary General, was a key figure in the serfs’ struggle and was described by Jordan Gebremedhin as the most distinguished intellectual and political leader of the 1940s. Sultan also opposed the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and was imprisoned for it.

Though named the Muslim League, the party was nationalist, using the religious designation to counter Ethiopia’s annexation efforts through the Orthodox Church. Despite this, Sultan maintained an alliance with Christian highlanders who supported Eritrean independence, such as Ras Asberom Tessema’s Liberal Progressive Party.

Sultan and other activists created networks between merchants and religious authorities, expanding charity organisations and establishing new Islamic schools and mosques in the early 1940s. This laid the foundation for Eritrea’s politically engaged Muslim intelligentsia. They viewed emancipation as crucial for a unified, multiethnic, and politically active Muslim community. Sultan consistently felt he led the Muslim League and never joined the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) or the EPLF.

Impact and legacy

The serf emancipation movement laid the groundwork for future political and social movements in Eritrea, contributing to a rising consciousness about human rights and social and religious justice. The British administration eventually gave in to the serfs’ demands. Three months after the Four Power Commission left, the British Military Administration began restructuring tribal organisations in western and northern Eritrea.

By June 1948, they had created 20 entirely new tribes, refashioned 8 former non-aristocratic tribes, and recast 5 former aristocratic tribes, electing 20 new chiefs and 591 subordinate chiefs, thus permanently altering the social organisation. Changes in the structure of education and the economy also led to the rise of a new elite, often from serf communities, who would go on to challenge the authority of the noble class and articulate their political demands in new terms.

As Trevaskis predicted earlier: “The Muslim leaders in Eritrea came to learn the political value of their Islamic connections during the latter part of the occupation. If they have reasons for discontent in the future, they will undoubtedly exploit them. Should they do so, their appeals are likely to command Muslim sympathy, entailing the threat of active subversion and encouragement to revolt.”

The armed struggle for independence indeed started in the western lowlands.

The serf emancipation movement in Eritrea during the 1940s was a pivotal moment in the region’s history. It not only challenged the existing social order but also laid the groundwork for future political and social movements including the ELF and the EPLF, ultimately contributing to the broader struggle for Eritrean independence.