Friday 22 November 2024

Nairobi protests and renewing Kenya’s geopolitical credentials

The Kenyan government is throwing its chips in with the west, assuming that it will enable it to its economic woes but he’s repeating mistakes of old.

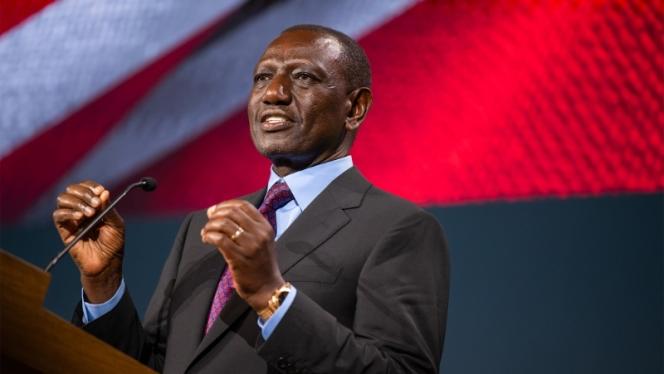

President William Ruto’s trip to Washington foreshadowed increasing political turmoil at home. A restive Generation Z has found renewed vigour by staging a series of protests across the country, including in Nairobi, triggered by a punitive Finance Bill heralding more austere and elevated taxes on the middle class. This is heightening the fault lines between the haves and have-nots in the country.

President William Ruto’s state visit to Washington, led to President Biden designating Kenya as a non-NATO ally. This designation, billed by Nairobi as a positive outcome, is the latest indicator that Kenya is swinging decisively towards Washington’s sphere of influence in the unfolding geopolitical contestation for dominance over the African continent despite Ruto’s insistence that the country faces “neither east or nor west; we face forward.”

Ruto’s trip to Washington is hot off the heels of his excursion to Brussels where he was accorded the opportunity to address the European parliament. The incumbent Kenyan government is throwing its chips in with the west on the assumption that it will enable it to address the raft of economic woes that it is confronting domestically, while reinforcing its credentials internationally.

The incumbent Kenyan government is throwing its chips in with the west on the assumption that it will enable it to address the raft of economic woes that it is confronting domestically, while reinforcing its credentials internationally.

The Kenyan government has faced severe financial challenges, with a public debt of close to $70 billion that requires a monthly repayment schedule of about $300 million. In March 2023, the government failed to pay the salaries of government officials, raising major alarm bells about the state of the national treasury. As Kenya’s finance cabinet secretary, Njuguna Ndung’u, stated, “the government is in a financial fix with nowhere to get more funds.”

Kenya is over-leveraged to Chinese debt for the infrastructure it has been building while the US was engaged in fighting the so-called “war on terror”. China accounts for more than 25% of Kenya’s external debt servicing expenditures, and the government is under pressure to source additional income streams. Ruto’s trip to the US is primarily fuelled by an agenda to pursue export promotion, increase trade, and leverage Kenya’s billed “Silicon Savannah” as the new frontier for global digital growth.

Renewing Kenya’s geopolitical credentials

Geopolitically, Ruto’s foreign policy has unabashedly tilted to the west, reaffirming Kenya’s long-standing security partnership with the US, notably in attempting to quell the threat of violent extremism in the Horn of Africa and ensuring maritime security across the Red Sea, which accounts for more than 12% of global seafaring trade. Paradoxically, it is Washington’s biased foreign policy in the Middle East that has undermined peace and security in this troubled region. Ruto has also cast his sail towards the west with his unequivocal support for Israel, despite the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issuing an order for Tel Aviv to cease its genocidal pummelling of Palestinians in Gaza. Additionally, Ruto has issued tacit support to Ukraine following its invasion by Russia in February 2024.

Kenya also confirmed its willingness to send police troops to accompany Haitian government forces and other troops from Caribbean and Latin American countries in a US-backed, United Nations-initiated Multinational Security Support Mission to Haiti. This mission aims to calm the restive Haitian nation, which is afflicted by marauding gangs that have undermined the rule of law and destabilised society. It would be tragic for Kenyan troops in Haiti to be repatriated to Nairobi in body bags, but this is the challenge of confronting virulent gangsters. A securitised and militarised approach to quell the chaotic situation in Haiti will not succeed in laying the foundations for stability without a nationally anchored, demilitarised, and peacebuilding approach to rebuilding the fabric of society. Washington’s historic role in destabilising Haiti through its engagement with the regimes in Port-au-Prince is a necessary contextual background that must be factored into any attempts to heal the society. In this regard, there is an equivalent need for a contingent of international peacebuilders who can work under the guidance of Haitian civil society and social movements to reclaim their space and shape the future of the country.

A securitised and militarised approach to quell the chaotic situation in Haiti will not succeed in laying the foundations for stability without a nationally anchored, demilitarised, and peacebuilding approach to rebuilding the fabric of society.

To be fair, Kenya has a distinguished 40-year record as a key contributor to United Nations peacekeeping missions, and the fraught Haitian excursion is more a case of continuity with a long-established role rather than a radical departure. In effect, Ruto is on a mission to renew Kenya’s geopolitical credentials, flex its international muscle, and accumulate brownie points for being a good global citizen.

Biden’s benediction of Ruto and Kenya as a non-NATO ally will enable him to further open the floodgates from the Bretton Woods institutions to access lines of credit from multilateral lenders, notably the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Ruto’s predecessor, Uhuru Kenyatta, followed a similar modus operandi and was quoted as saying that given the choice between debt and infrastructure expansion and growth, he would embrace borrowing to “develop” his society. In this regard, there is an element of continuity in Ruto’s engagement with Washington, which can be traced back to the 1960s when former US President John F. Kennedy provided scholarships for young Kenyans, including Barack Obama’s father.

Ruto began his term waxing lyrical about the need for the African Union to function as a convening platform for the continent’s engagement with global actors. However, he subsequently acknowledged that African leaders have deliberately kept the AU weak and institutionally incapable of effectively convening its constituent members and challenging them when they deviate from the established principles of peace, security, and democratic governance that they have all adopted. A weakened African Union is a trade-off that African leaders believe will give them leeway to do what they like in their own countries. However, it is now evident that a weak AU translates into 55 weak African countries which cannot stand up and fight for their own continental interests against aggressive and predatory global actors.

A weakened African Union is a trade-off that African leaders believe will give them leeway to do what they like in their own countries.

As a result, key continental initiatives that could unleash the power of African entrepreneurship and the creativity of her youth, such as the AU Protocol on the Free Movement of People, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and the Single Air Transport Market, have become hamstrung and mired in bureaucratic purgatory, exposing the short-sightedness of the continent’s so-called leadership. Trade between African countries is still less than 13% of their total trade, the lowest globally, in comparison to 44% in the Americas, 63.8% in Asia & Oceania and 66.9% in Europe.

Africa can increase its economic growth by trading more effectively with itself and becoming more self-sustaining if it relies on generating intra-continental income streams rather than repeating the tried-and-failed model of excessive borrowing from major powers in the west or east and international financial institutions, which have punitive debt repayment conditions.

Trade between African countries is still less than 13% of their total trade, the lowest globally, in comparison to 44% in the Americas, 63.8% in Asia & Oceania and 66.9% in Europe.

There is a poverty of imagination due to African leaders’ suspicion and lack of confidence in their own home-grown ideas, analysis, and strategies for the upliftment of the continent. This servile mindset is a throwback to Africa’s legacy of slavery, colonialism, and apartheid, which were paradoxically designed and executed by countries that fall under the rubric of the so-called West, with Washington at the helm.

Africa’s leaders continue to behave as useful idiots for geopolitical agendas, whether it’s China’s not-so-subtle incremental conquest of the continent in exchange for unbridled access to natural resources and land, as part of its 2049 quest to become the planet’s leading hegemon, or Russia’s crass takeover of the Sahel for the purpose of extracting natural resources, a model perfected by the Americans and Europeans.

Ruto’s latest excursion into the bosom of Washington’s Beltway replicates a tried, tested, and failed model which will lead to even greater indebtedness to Washington and the Bretton Woods institutions. It also maps a negative trajectory for the livelihood of Africa’s youth, who will be tasked with paying back the unsustainable debt that will be incurred from this wholesale excursion. Kenyan civic and societal actors, as well as their counterparts across Africa, need to exercise their role as the “owners” of their countries and agents of their democracies, where they remain viable, instead of blindly trudging down the path of becoming wholly-owned subsidiaries of Washington-Incorporated, Beijing-Industries, or Moscow-Mercenaries.

The continent’s fate and future will only become more promising when African leaders are held to account by their citizens, reviving the incomplete Pan-African project of economic integration based on the unifying principle of continental sovereignty and a determination to work collectively with fellow Africans to address the multiple challenges that can only be worsened by opening the floodgates for infiltration and re-conquest by global predatory actors.