Thursday 21 November 2024

Somalia’s paralyzed parliament

For Somalia’s parliament to be fit for purpose, it needs to cultivate a culture of respecting and relying on external expertise and be better connected with the demos.

The purpose of a parliament can be summarised as the cornerstone of democratic governance: creating laws, representing the electorate, overseeing the government, and fostering a stable and just society. Parliaments provide a structured environment for political debate, decision-making, and accountability, ensuring that the will of the people is reflected in the governance of the country. However, in this article, I will expand this definition to encompass all forms of governments, including non-democratic and guided democracies, as I briefly discuss the history of Somalia’s parliaments.

The Althing in Iceland, established in 930 AD, is considered the oldest surviving parliament in the world. It began as an outdoor assembly of the country's chieftains and evolved into a modern legislative body. The largest parliament in the world by the number of MPs is China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) with nearly 3,000 members. Conversely, Tuvalu, a small island nation in the Pacific Ocean, has the smallest parliament (Fale I Fono) in the world with only 16 members. This unicameral body reflects the country’s small population and operates with minimal infrastructure.

The Somali Parliament, also known as the Federal Parliament of Somalia, has undergone significant changes since its inception, reflecting the tumultuous history of the country. During the colonial and early years after independence, the first parliament, known as the National Assembly, was established. It was eventually dissolved in 1969 following Siad Barre’s coup d'état.

The years of the Barre regime were characterised by an environment of severe political repression. A Supreme Revolutionary Council was formed, which governed the country as the sole legal political entity in Somalia. In 1976, the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (Xisbiga Hantiwadaagga Kacaanka Soomaaliyeed - XHKS) was founded, which eventually allowed limited representation within people’s assemblies. However, the XHKS was the sole legal party and was the only one allowed to contest the sham elections held in 1979. The regime eventually collapsed, leading to civil war and the breakdown of state institutions.

In 2000, a transitional government was formed, including a Transitional National Assembly as part of peace efforts. In 2004, the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) succeeded the TNG, and the Transitional Federal Parliament (TFP) was established. In 2009, the TFP was expanded to include more members from various clans to promote inclusivity and peace. Members of the house were not directly elected by the public but were appointed as representatives of the various clans.

This was followed by the latest phase in 2012, when the Federal Government of Somalia was established, replacing the TFG. The Federal Parliament of Somalia was inaugurated, consisting of the House of the People (lower house) and the Upper House (Senate). In 2016, the first election under the new federal system was held, further solidifying the parliamentary structure. In 2021, the most recent parliamentary elections were conducted amid security and political challenges.

Throughout its history, the Somali parliament has faced numerous challenges, including political instability, security threats from militant groups, and clan-based divisions. Despite these obstacles, it remains a central institution in Somalia’s efforts to achieve lasting peace and democratic governance. Among its many challenges, this article will focus on the lack of capacity and unbalanced representation of all constituents.

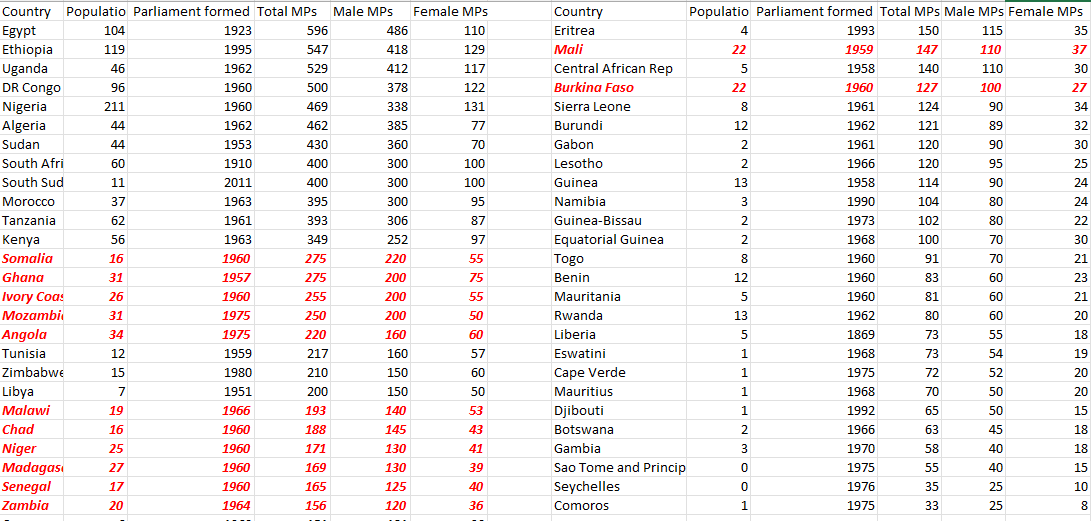

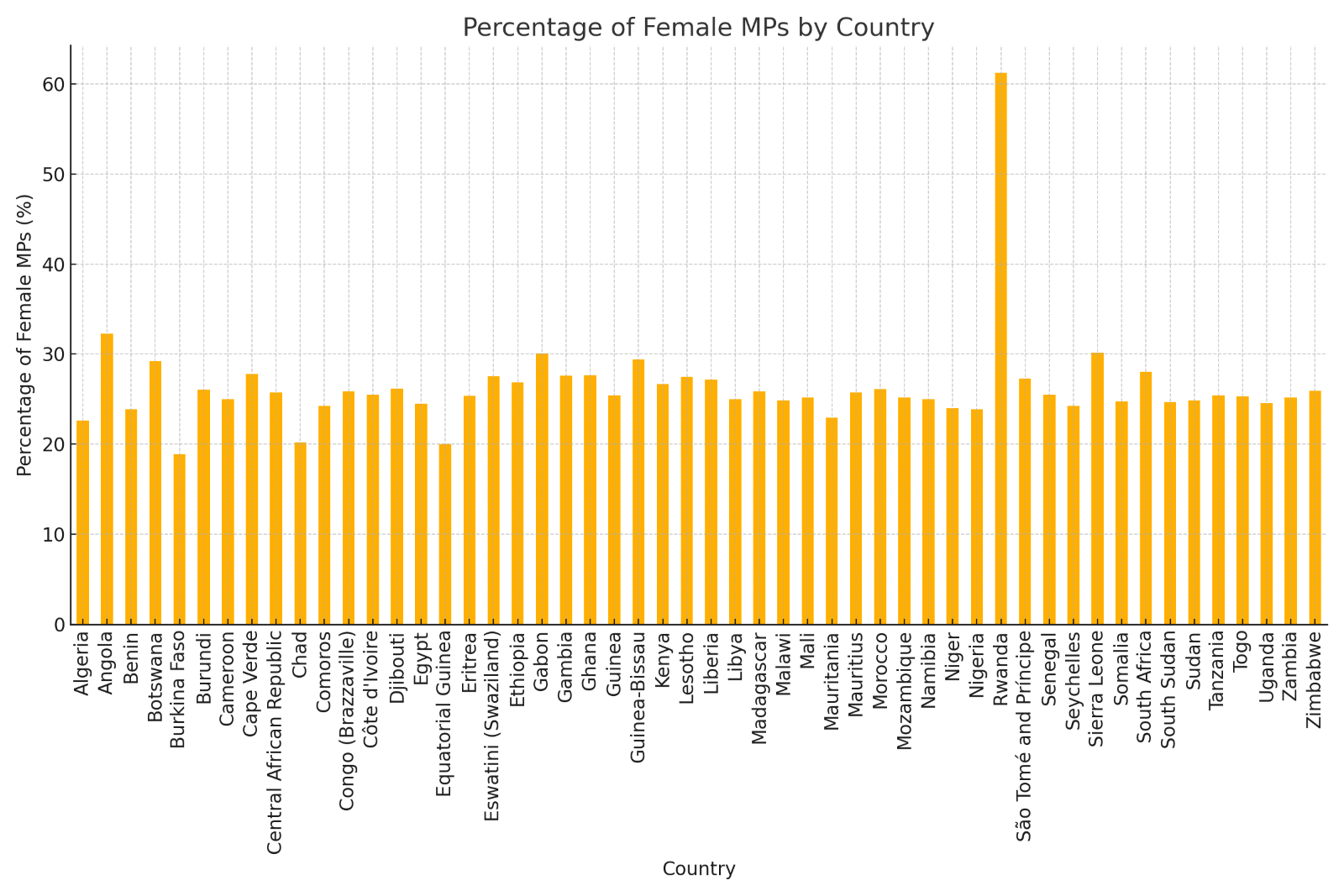

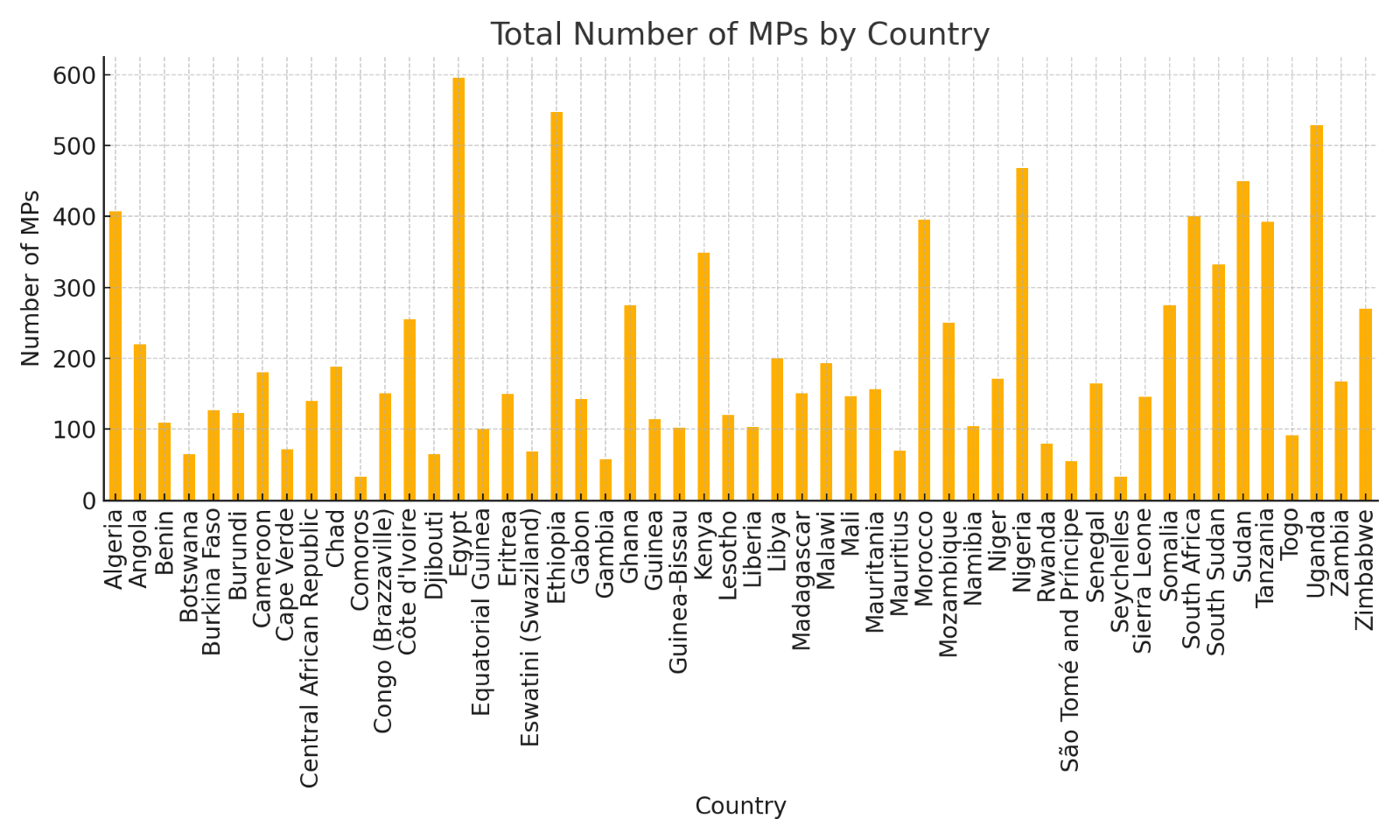

Analysing the total number of MPs in African countries highlights how legislative representation, as well as gender balancing, is prioritised. Despite having a smaller population, Somalia maintains a relatively large parliament without a logical basis for its size. For example, countries like Nigeria and Ethiopia have large populations and correspondingly large parliaments, reflecting a direct approach to representation. In contrast, smaller nations such as Seychelles maintain minimal parliamentary sizes, which is practical given their limited populations. The data below confirms that Somalia is an outlier both in terms of size and skewed gender representation.

Source: World Bank

From a historical context, older parliaments such as those in South Africa, dating back to 1910, and Egypt have established structures that often result in larger legislative bodies. Newer parliaments, like South Sudan’s, established in 2011, are still evolving and adapting to their legislative needs. Countries like Rwanda demonstrate significant strides in gender parity, often influenced by legal mandates and policies promoting female participation. Somalia started as a functioning democratic government, with the first democratic elections held in 1964, followed by another round in 1967. These elections were generally free and fair, reflecting a strong commitment to democratic principles. During this period, leaders like Aden Abdullah Osman Daar, who became the first president, and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, his successor, played pivotal roles in maintaining democratic governance. Somalia was one of the few African countries where a sitting president was peacefully succeeded by another through democratic elections. Abdi Ismail Samatar’s book covers this in detail, calling Somalia’s politicians Africa’s First Democrats.

Source: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA)

Other countries still show a predominance of male MPs, indicating areas where policy interventions could enhance gender balance. This historical context impacts the development and structure of parliamentary systems. Somalia’s MPs are not elected but selected by tribal chiefs. It appears that the selected individuals are not necessarily the brightest or wisest representatives of their tribes, leading to suboptimal outcomes in parliament.

Source: World Bank

What is to be done?

The literature in this field promotes the concept of the “best functioning parliament,” which is contested and dependent on various criteria such as efficiency, transparency, representation, public trust, legislative productivity, and adherence to democratic principles. However, some parliaments, such as the Norwegian parliament (Storting) and Swedish parliament (Riksdag), are often highlighted for their exemplary functioning based on these criteria. The following is a brief overview of the criteria for a well-functioning parliament:

- Transparency: Open access to information, public sessions, and clear communication of decisions.

- Representation: Fair and diverse representation of the population, including minorities and marginalised groups.

- Efficiency: Streamlined legislative processes, effective committee systems, and timely passage of laws.

- Accountability: Robust mechanisms for holding the government and parliamentarians accountable for their actions.

- Public Trust and Engagement: High levels of public trust and opportunities for citizen participation in the legislative process.

These examples illustrate some of the best practices in parliamentary functioning, but the effectiveness of a parliament can also be influenced by the specific political, cultural, and historical context of a country. Parliamentary behaviour encompasses the conduct, norms, and practices exhibited by MPs during sessions and other parliamentary activities. Notable examples of exemplary parliamentary behaviour include respectful debates focused on policies and issues rather than personal attacks. This is typically outlined in the by-laws of parliaments and vigorously enforced by the speaker and deputies. Unfortunately, this is often ignored in recent Somali parliaments.

MPs are expected to actively participate in committee meetings, offer constructive input, and conduct thorough reviews of legislation and policies. They are also expected to maintain transparency about their actions, voting records, and decision-making processes with their constituents. However, the current parliamentary structure and methods make this redundant because MPs often secure their seats through tribal affiliations rather than electoral merit. As a result, their real constituents have little interest in maintaining any level of transparency regarding their parliamentary activities. Corruption and conflicts of interest are rampant, with MPs often absent for long periods and rarely contributing to debates or discussions during the parliamentary term.

Since the MPs do not truly represent the interests of their constituents, it is difficult to discern whose needs and concerns they advocate for within the parliamentary framework. It is rare to see a Somali MP meeting with citizens to discuss and address their concerns directly. There are no regular meeting schedules between MPs and citizens, nor are there published emails or phone numbers to contact Somali MPs. Addressing this issue is not a major task but requires the will and motivation to improve the effectiveness of the Somali parliament. This is a serious problem that needs urgent attention to move the country forward.

Around the world, MPs follow established rules and procedures, contributing to the orderly conduct of parliamentary business. For example, the Japanese Diet emphasises politeness and order during sessions, with strict rules about speaking times and the manner of addressing colleagues. While Somalia leads in some private sector innovations, its parliament has failed to embrace this spirit. Other branches of government like the judiciary and the cabinet have similarly failed. It is common practice, almost an accepted rule, for ministers, the prime minister, and even the president to use social media tools to communicate with citizens rather than official channels. By understanding and addressing these variations, Somalia can enhance the effectiveness and inclusivity of its parliamentary systems, fostering better governance and representation for its citizens.

Steve Liddle, a New Zealander researcher, and I developed online lessons for the Somali School of Government. This self-funded initiative aims to educate the diverse members of parliament on the procedures and long history of parliamentary rules. When we developed this, there had been no parliament in Somalia for more than a generation, and there was an identified need to instruct MPs in the traditions of a functioning and transparent national debating chamber.

There is a series of ten backgrounders designed to upskill all MPs and civil servants in the history of liberal democracy as well as in parliamentary and electoral processes. By providing these overviews as reference material, the Somali School of Government aims to establish common understandings for all politicians and those in public service. It is hoped that a grasp of this history and these processes will ensure a smooth transition to the disciplines required of representative government. Furthermore, it is hoped that such knowledge will enable the achievements of such a government and clarify the boundaries and interwoven responsibilities of both tribal and parliamentary representation.

--