Tuesday 22 October 2024

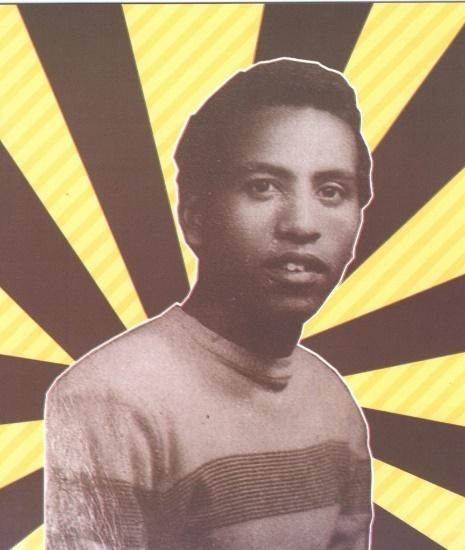

Tewolde Redda: the voice of the people’s cause

Author and researcher Mohamed Kheir Omer reflects on the life and work of the musician Tewolde Redda.

Tewolde Redda is one of Eritrea’s most prominent artists, renowned for his commitment to the people’s cause. His legendary song Shegey Habuni (Give Me My Torch), first performed in 1965 at Cinema Odeon, resonates as a powerful cry for freedom. Despite its metaphorical lyrics, the song has been widely interpreted as a call to regain liberty, and its relevance endures to this day.

Since leaving Asmara in the late 1960s, Tewolde has not returned to Eritrea due to his opposition to the Afwerki regime. He remains steadfast in his support for the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), which he joined in 1962. He entered the armed liberation struggle alongside his daughter, who tragically lost her life, while he survived. He moved to the Netherlands in 2002 and has lived there since, leading a reclusive life.

More than just a songwriter, musician, and singer, Tewolde Redda is a multifaceted talent—playwright, poet, sportsman, and skilled electrician. He was the first to design an electric version of the krar (a traditional string instrument), which was adopted by Ateweberhan Segid, the father of traditional music in the Asmara Theatre Association (MTA), who was 25 years Tewolde’s senior and significantly impacted the evolution of Eritrean music. Additionally, Tewolde was an accomplished mechanic and athlete, engaging in cycling, football, and even boxing.

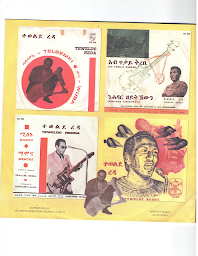

In an interview with ERIPM, Tewolde said that he served as the musical producer and public relations officer at the renowned Asmara Theatre Association (MTA). As the go-to person for refining songs and lyrics, he collaborated with poets and musicians until the material was stage-ready. He mentioned that only Osman Abdulrahim, who is eight years his junior, would come fully prepared with complete lyrics and rhythms.

As a public relations officer, Tewolde coordinated requests for performances and events, taking the MTA’s scripts and music to the Censorship Office. Although the office was staffed by sympathetic Eritreans, it was cautious not to endorse any content that might be viewed as defiance against Ethiopian occupation.

At that time, music was recorded on reel-to-reel tapes, which were not widely accessible, so people would gather in cafés and bars to listen. They used vehicles equipped with microphones to roam the city, promoting their productions and concerts, or brought tapes to bars to offer sneak previews of their latest works. When asked why the music of the 1960s remains timeless, Tewolde attributed it to the intense effort, discipline, and camaraderie among the artists.

Regarding how Shegey Habuni passed censorship, Tewolde recounted that the censor, who was friendly towards him and shared his name, initially exclaimed: “Do you want to get us in trouble, my son?” when he first heard the song. Tewolde convinced him that it wasn’t political, explaining that the inspiration came from observing a young boy asking for his torch during the traditional Meskel celebrations. With that clarification, the song was approved. However, after it received an overwhelming reception at its first performance, Ethiopian officials demanded that all song scripts be translated into Amharic. Due to its political implications, the song was never recorded in a studio. Under the current circumstances, he does not wish to sing the song in public.

At the age of 16, he heard of a music contest in Asmara and decided to compete by choosing a popular song of the time, Asmeretei. He practised using a borrowed guitar. According to the Norwegian music enthusiast Vedmund (also known as Kidus Berhane), who remixed and recorded his songs and wrote about him, Tewolde prepared himself for the occasion by fixing his hair and styling himself like Elvis Presley, right down to the leather jacket. He was the youngest of 14 contestants in the competition and was declared the winner. This victory gave him the confidence to pursue his musical career. The gift of an electric guitar from his older sister’s husband provided a solid beginning.

By the 1950s, Asmara had several Italian bands, and with the lifting of the Italian racial laws, Eritreans gradually began joining them and forming their own bands. In the cosmopolitan atmosphere of Asmara, Tewolde grew up fluent in Tigrinya (his mother tongue), Amharic, Arabic, and Italian. In 1961, he was one of the pioneers, alongside Tekabo Nemariam, who started Mahber Teater Asmara (MaTA), the Theatre Association of Asmara. He recorded with Philips and Amha Records in Addis Ababa and owned his own music shop (Yared), label, and recording studio.

He sang for love, for life and its challenges, and for family, offering advice to the young through his songs. One of his famous hit songs is Seb Mukhaney, which begins:

Being human living on the earth

Being human living on the earth and unable to cope

We are its soil and returning to its embrace

From dust to dust

we think we live forever, yet life is short

Live in love and kindness

Avoid sin and mistakes

In the end, what remains?

The legacy you leave behind

Not wealth nor fame

Enjoy the warmth of family,

The laughter of siblings.

Tewolde was born in the Tzetzerat neighbourhood of Asmara on December 27, 1941. He arrived at a critical historical juncture, just a few months after the Allied forces defeated Italy and Britain took charge of Eritrea. He was the youngest and only boy in a happy family and attended Schola Vittorio Emanuele and later Hibret School.

His father, Redda Tesfamariam Game (Enda Mefles), was from Rokhoyto in Akle Guzai, while his mother, Silas Tessema Neuus (Enda Turkay), hailed from Lego Sarda. He recalls meeting key figures of the independence movement, such as Abdulgadir Kebire, Ras Tesemma Asberom, and Woldeab Woldemariam at the Jeberti Club, later renamed ‘Nadi Al Shabab’—a youth club that inspired him to join the liberation struggle.

Tewolde said that he was deeply influenced by the great Syrian-Egyptian musician Farid Al Atrash. He also discovered and mentored Tebereh Tefahunay, one of the few female artists performing on stage, writing many of her songs. As an artist, Tewolde’s low profile allowed him to support the fedayeen—guerilla fighters who undertook special missions in towns—by hiding arms for them when they visited Asmara.

Tewolde's musical style has attracted international attention. A documentary film on Tewolde Redda, titled ‘Shigey, my flame’ and directed by Marc Schmidt, was produced in the Netherlands in 2009. In the introduction, it states: “The song Shigey Habuni lives on in the hearts of all Eritreans worldwide. It symbolised the long and harsh fight against the Ethiopian occupation. Nowadays, Eritrea is an independent country, but the writer and singer of this song, Tewolde Redda, seems to be forgotten.” The film was also reviewed in an international journal, which described him as the best guitarist that Eritrea has produced.

Yared Tekeste, a promoter, festival producer, DJ, and passionate music enthusiast, is the son of Tekeste Goitom, also known as “Trillo,” one of the founders of Ma.M.Ha.L. (the Association for Advancing National Culture), which preceded the Asmara Theatre Association (MTA). He describes Tewolde’s music as avant-garde, emphasising how he introduced innovative musical scales into traditional Eritrean music, creating dynamic sounds that have shaped modern popular music. Yared believes that Tewolde’s pioneering approach to guitar playing and his electrification of the krar transformed the trajectory of Eritrean music forever.

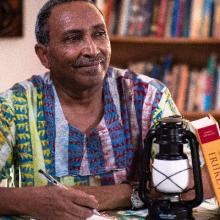

Tewolde is humble, doesn't like talking about himself, and rarely does interviews, but he is very friendly. It was the late Jelal Yassin who introduced me to Tewolde Redda. In a recent conversation, Tewolde mentioned that he and Jelal were very close and spoke on the phone almost daily. On the night Jelal passed away, 15th May 2022, they had a long conversation during which Jelal, feeling unwell, said he was “in death’s quarter” and felt dizzy. Tewolde recalled hearing a bell ring, likely Jelal calling for help. The next day, Tewolde learned of Jelal’s passing. He spoke highly of Jelal’s kindness, sharing that Jelal had sent him money and tickets to visit his daughter in Sudan, unannounced, whom he hadn’t seen in years. Although Tewolde was hesitant due to his eyesight issues, Jelal made the reunion possible—a relationship that transcends all boundaries.

Tewolde remains deeply affected by the loss of his 30-year-old son in 2014. He currently lives in the Netherlands. At 83, age and eyesight problems have taken their toll on him, but his memories are intact, and he remains engaged, even though his musical involvement has dwindled.

The first time Kidus Berhane, the Norwegian music enthusiast, met Tewolde in the Netherlands, he told him: “I am not like the other singers of my time. I performed with Mahmoud Ahmed, Tilahun, and others, but I was never making music to be popular. I was a revolutionary singer, singing for the love of my country and my people, which was my main motivation.”

Reflecting, perhaps, on the dictatorial regime ruling Eritrea, he added: “I lost belief in my country. I have not lost my voice, but my enthusiasm for performing has diminished, along with the loss of my country. I am still creating some melodies and lyrics, and I have many songs that I have not released. One day, I might share them with my people, but not now. Perhaps when I feel better about things.” Unfortunately, that feeling has not yet come.