Thursday 21 November 2024

Echoes of a broken revolution

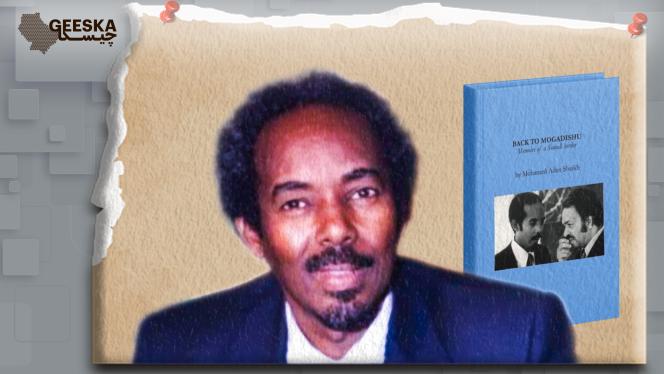

Back to Mogadishu: Memoirs of a Somali Herder provides a poignant account of the Somali Democratic Republic’s tumultuous decline. It chronicles the hopes, struggles, and eventual disillusionment of a key political figure during the country’s most formative and tragic years.

Dr Mohamed Aden Sheikh (may Allah SWT have mercy on his soul), a former minister and cardiologist, begins his memoirs with a poignant observation: “When a Somali writes about what has been happening in his country since 1991, he can only do so with a heart full of sadness, anger, and even a bit of shame.” This sombre opening serves as both a lament and a reflection of the collective disappointment of a generation of intellectuals who witnessed the collapse of the state and the violent unravelling of a post-colonial dream. For Sheikh, 1991 marked not just the end of the Somali Democratic Republic but also a moment of profound personal tragedy, as a man who had once been a key architect of its “revolutionary” vision.

In this book, Dr Sheikh sketches a portrait of the regime’s political machinery, positioning himself as both an active participant and an observer. By 1982, after allegedly learning of Siad Barre’s clandestine consolidation of power a decade earlier, Sheikh acknowledges that his position in the government had become morally untenable, and he soon became a “victim of his own drum”. In many ways, his memoir is a moral reckoning with his continued involvement in a system that, by the time of his arrest, was descending into tyranny. His delayed dissent highlights the complexities of loyalty, power, and moral compromise in the face of political ambition. Sheikh explores themes and questions similar to those in Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, particularly the moral dilemmas of participating in a regime that ultimately turns against itself.

In many ways, his memoir is a moral reckoning with his continued involvement in a system that, by the time of his arrest, was descending into tyranny.

Upon first reading Back to Mogadishu, one is immediately struck by the profound sense of optimism that pervades its reflections on the regime’s early years. This mirrors the broader zeitgeist that swept across Africa in the 1960s and 1970s, as newly independent states sought to overcome the violent and extractive legacies of colonisation. Siad Barre himself came to power promising to restore the nation “to the place from which it had fallen”. “We will build a great Somali nation, strongly united and welded together to live in peace,” he said in his first speech after the 1969 coup.

Yet, the doctor’s optimism is tempered by a remarkable pragmatism, often absent from the grandiose promises of industrialisation made by Barre and many other African leaders at the time.

Sheikh’s political vision was deeply shaped by the dual forces of collectivism and “fatalism” rooted in the harsh realities of Somali pastoral life, which he experienced during his early years in the bushlands of Mudug. His symbolic journey, reflected in the state’s own odyssey, from the pastoral world to the political centre of Mogadishu allowed him to view the newly formed Somali Republic not as an abstract entity, but as a living nation of interconnected nomadic and urban communities.

In hindsight, the doctor’s pragmatism perhaps revealed his acute awareness of the fragility within the political structures he had helped build. Nevertheless, Sheikh maintained that at the time, the process of “social and economic emancipation”—which he termed the “Somali Revolutionary Process”—seemed a necessary path, even under the watchful eye of the military junta.

His symbolic journey, reflected in the state’s own odyssey, from the pastoral world to the political centre of Mogadishu allowed him to view the newly formed Somali Republic not as an abstract entity, but as a living nation of interconnected nomadic and urban communities.

At the height of the “revolution”, Sheikh recounts a fiscal utopia in which the state deliberately avoided the burden of debt and effectively harnessed its human capital through self-managed healthcare centres. “Somalia didn't seem like a poor country to us, he observed. His account of these early successes, where the Somali Republic briefly appeared to defy the odds of underdevelopment, is, however, tempered by the reality that this progress was short-lived. As the political situation deteriorated and internal pressures mounted, these early achievements quickly unravelled. Sheikh’s retrospective analysis serves as a sobering reminder of how fragile some of these gains are in postcolonial African states.

Dr Sheikh's description of the Somali Republic prior to the 1969 “bloodless” coup draws clear parallels with Frantz Fanon's incisive critique of post-colonial African elites.

Fanon’s concept of the “national bourgeoisie”—the domestic inheritors of colonial rule—finds a tragic embodiment in the leadership of the Somali Republic in the years following independence. Fanon observed that many post-colonial African elites, rather than fulfilling their people’s revolutionary aspirations, entrenched themselves in power, perpetuating the same divisions and autocratic structures left by the colonialists. Sheikh dispels any nostalgia for the so-called “golden era” of Somali politics, during which figures were labelled by Abdi Samatar as Africa’s First Democrats. He describes the political landscape of Mogadishu in 1969 as one dominated by self-serving elites, ruthlessly competing for power in the capital and disconnected from the predominantly pastoralist population, to whom they became “worthless”. A popular joke at the time was that MPs only visited their constituencies when they needed to be re-elected.

Fanon’s concept of the “national bourgeoisie”—the domestic inheritors of colonial rule—finds a tragic embodiment in the leadership of the Somali Republic in the years following independence.

This urban-rural divide bears unsettling similarities to aspects of Somaliland’s current parliamentary system, where political dynamics remain deeply fragmented along tribal lines, and similar patterns of elite detachment persist. Though the demographics and socio-political context have shifted since the regime’s collapse—and even more so since the publication of his memoirs—Sheikh’s critique of the disconnect between ruling elites and the wider populace remains a sharp and enduring commentary on the challenges of state-building in the Horn of Africa.

A recurring theme throughout Back to Mogadishu is the tension between tradition and modernity, a conflict that shapes much of Sheikh’s political and intellectual reflections. Initially, this tension is explored within the context of pastoralism and national development, but it deepens in chapter seventeen, where Sheikh addresses what he terms the “fossilisation” of contemporary Muslim scientific culture. Here, he offers a sharp critique of the decline of Islamic theological institutions, lamenting their failure to evolve alongside modern scientific advancements, as they once did. Yet, this valid critique also highlights a notable absence of Islamic theology in his own political vision.

he offers a sharp critique of the decline of Islamic theological institutions, lamenting their failure to evolve alongside modern scientific advancements, as they once did.

Sheikh’s openly secular orientation is perhaps one of the more contentious aspects of his political legacy, provoking both admiration and disdain among Somalis, both at home and in the diaspora. His strong belief in secular governance exemplifies a broader ideological divide that has become more pronounced in Somalia since the regime’s collapse where religious institutions and figures have grown in prominence to an extent not imaginable during the Barre regime.

In one telling anecdote from chapter thirteen, Sheikh recalls an interaction with what he calls an “Islamic fundamentalist,” where he seemingly equates the Somali greeting subax wanaagsan (good morning) with the Islamic greeting As-salaamu Alaikum (Peace be upon you). While this may seem trivial, it reflects a deeper divide between his secular vision and the growing significance of religious identity in Somali society. In his final chapters, Sheikh delivers a scathing critique of the rise of fundamentalism, while also nodding towards the political pacifism of Sufism, which he saw as a potential bridge between tradition and modernity.

Conclusion

As a member of the diaspora born after the Annus Horribilis of 1991 and into the renewal of Somaliland, my reading of Back to Mogadishu is inevitably shaped by a generational contrast. My understanding of state collapse, like many, is removed from direct experience, influenced not only by stories of despair but also by narratives of resilience and renewal. During my lifetime, the cities of my forefathers have grown exponentially, with cold war-era external dependencies replaced by a new pride in self-sufficiency and diaspora-led investment. This generational perspective allows me to view Sheikh’s words not just as an account of loss, but as a testament to the enduring resilience of the Somali people, who have uniquely adapted to new realities both in the Horn of Africa and across the globe.

Back to Mogadishu is more than a personal memoir; it is a personal reflection on the promises and failures of post-colonial nation-building in one of Africa’s most important test cases. Dr Mohamed Aden Sheikh’s journey—from an idealistic architect of a socialist revolution to a disillusioned witness of its fragmentation—encapsulates the moral paradoxes faced by many African intellectuals. His involvement with a regime that ultimately betrayed its socialist ideals invites necessary criticism, particularly regarding the moral compromises that accompanied his prolonged participation. Yet, his reflections offer crucial insights, urging us to confront uncomfortable truths about power, responsibility, and the enduring consequences of poor leadership in the Horn of Africa.