Thursday 21 November 2024

Memories of khalwa: traditional Quranic education in Eritrea

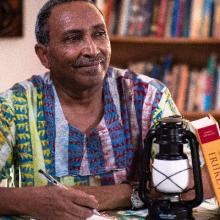

Mohamed Kheir Omer recalls his memories of khalwa, the setting of his traditional Quranic education, in Eritrea

Like most Eritreans born into Muslim families, my first steps into education began in a Quranic school, or khalwa, in the late 1950s. This was long before George Bush’s so-called War on Terror in the early 2000s, after which these spaces came to be thought of as terrorist training grounds. This was also before Saudi-inspired Muslim groups who call themselves salafi began to emerge.

I attended a khalwa in Agordat, western Eritrea, which was overseen by the late Syedna sheikh Mohamed Abdella Idris and financially supported by the late Khalifa (an honorific for leader) Abdulragib Mohamed Sadig. The khalwa was situated within the largest section of Abdulragib’s compound, among a garage of old buses and vehicles. We had no clue why they were not operating, but those vehicles became our playground.

This was an example of how affluent individuals contributed to education. It was at this khalwa that I received my initial instruction in Arabic script and studied the Quran, which I found rewarding when I joined a formal school. However, our understanding of the Arabic verses was minimal. We hardly understood what the verses meant, a challenge faced by many non-Arabic-speaking Muslims and, in some cases, Arabic speakers.

The khalwa operated in two sessions: one in the morning and one in the afternoon. In the early mornings, we would gather around Syedna Abdella. Multiple groups would be studying different chapters of the Quran simultaneously. Syedna Abdella possessed an extraordinary memory; he could recite verses from various chapters with remarkable speed, shifting from one group to another. I still find it fascinating how he managed to do so effortlessly, moving from one chapter to the next in seconds. The Quran comprises 114 chapters or surahs, each beginning with: “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”.

We wrote our lessons on wooden tablets known as luh with handles at the two ends, using ink made from dewaat (a mixture of carbon and glue), and our pens were made from thin straws made of corn stems. The wooden tablets were cleaned and whitened with jir (limestone).. The use of tablets is widespread throughout Africa. In his book, The Walking Qur’an, Butch Ware, reflects on the symbolism of the use of tablets and pens across Africa:

“The reed pen of the Qurʾan school stands in for the Pen of Power. The wooden tablets are explicitly likened to the tablets on which Mūsā (Moses) received the commandments that he carried to the children of Israel.”

In the evenings, we recited the passages we had written earlier in the day in front of Syedna. While it was not mandatory for us to recite from memory, it was encouraged. The ability to memorise large portions of the Quran is a cherished achievement in the Muslim community and an individual who memorises it all is given the title hafidh.

After recitation, we would wash the wooden tablets using handles attached at the front and back, preparing them for the next day’s lessons. Throughout the rest of the day, older students would instruct the younger ones in Quranic studies.

These khalwas were attended by both boys and girls, unlike the government schools of that period, which were not mixed. To request permission to leave for necessities, one would stand in front of the sheikh and indicate with one or two fingers: one finger for the toilet and two fingers for water. In this way, we learned a form of sign language.

As children, our greatest joy was celebrating a milestone in someone’s Quranic studies, an event known as shirafa. Some began this journey early with Surah Al-A’la, while others embarked on it upon reaching Surah An-Naba in the 30th juz (section) of the Quran. During a shirafa, the student would adorn their wooden tablet with colours, marking their first foray into art at the khalwa. Some students displayed remarkable talent in this painting, perhaps indicating an early aptitude.

When someone achieved a shirafa, they were expected to bring a large round pancake, known locally as gurassa or kitchet, and tea to share. If the student hailed from a relatively affluent family, the anticipation was palpable, especially if the gurassa was made of white wheat flour (fino) and perhaps accompanied by more tea. Most of us came from modest backgrounds, eagerly anticipating such occasions, particularly when the treats were made from white flour, a delicacy for us at that time. Though we were unfamiliar with brown bread, all the bread we ate came from brown sorghum. Eating together in a large group added to the excitement compared to eating at home.

When it was time to eat, we would retrieve our small cups of tea from home, a source of great anticipation. We would then share it equally, learning the value of sharing. Each person received a portion of the gurassa and a cup of tea. At the end of each day, we eagerly awaited the signal to depart, racing each other to see who could be the first to leave. Syedna or our sheikh had a leather whip, which he used to punish the students, but he did so with a sense of humour. This approach made the punishments, even when strong, more bearable.

Both Islam and Christianity were introduced to this region at a very early stage; Christianity around the middle of the 4th century and Islam around the 7th century when the first Muslim refugees arrived in this region fleeing persecution in Mecca. The Orthodox Church in the region is one of the oldest churches in the world. Massawa has the oldest mosque outside of Arabia, with its praying direction, qibla, pointed towards Jerusalem, not Mecca. This occurred long before Christianity was re-exported from Europe in different forms back into the Middle East and Africa more broadly. Muslims in what is now Eritrea formed two-thirds of the population in 1910, and according to the Italian census in 1905, based on estimates where it was difficult to assess the nomadic population, which was incidentally predominantly Muslim.

Jonathan Miran has written extensively on the history of Islam in Eritrea. He notes: “In a very real sense Eritrea’s heterogeneous Muslim societies reflect this kaleidoscopic historical configuration: they belong to different ethnic groups; speak a variety of semitic, cushitic and Nilo-saharan languages; practise various modes of production and are socially and politically organised in diverse ways. More importantly, for our purposes, Muslim societies in Eritrea have adopted Islam in distinctive periods and in different ways and have appropriated Muslim beliefs and practices in varying modes and intensities.”

According to Miran, several holy families played pivotal roles in the transmission and propagation of Islamic religion, law, and culture in the areas extending between the Red Sea and the Nile Valley during the period of “Islamic revival.” One of these families was the Ad Shaykh holy family, a revered family in Eritrea. The newly established Khatmiyya tariqa, founded by Muhammad Uthman Al Mirqani (b. Mecca, 1794-1852), was particularly engaged in spreading and revitalising Islam. Additionally, traders and holy men associated with the politically potent Belew Naib family, delegated by the Ottomans to rule Massawa, also played a significant role in the spread of Islam.

Joseph Venosa, who completed a PhD dissertation on the contributions of Muslim intellectual activists in shaping a national Eritrean identity, explored their significance within the Eritrean Muslim League (EML), the largest and most prominent nationalist organisation that emerged during the 1940s and 1950s. He adds: “The ELM emerged as the first genuine pro-independence organisation in the country to challenge both the Ethiopian government’s calls for annexation and international plans to partition Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia. The league and its supporters also contributed to the expansion of Eritrea’s civil society, formulating the first substantial arguments about what made Eritrea an inherently separate national entity.”

Eritrea is a secretive state where even the population size is treated as confidential. Official estimates put Eritrea’s population at about 6 million, although there hasn't been an official census since independence. However, experts who monitor the region estimate the actual resident population to be between 2.5 million and 3 million. The government maintains that the number of Muslims equals the number of Christians, and disputing this is not permitted.

The government fails to uphold religious freedoms and values. It officially recognises Islam and only three Christian denominations. Hundreds of prisoners, including Muslims and Christians, have been detained for over two decades, some since the state’s inception, persecuted for their beliefs, with only a few within the regime aware of their whereabouts. The Jehovah’s Witnesses and Pentecostal denominations have been particularly affected among Christians, with several pastors, university professors, and the sole psychiatrist in the country imprisoned for many years, their fate unknown.

The case of Christians persecuted for their beliefs is globally known, as there are many Christian advocacy organisations. Persecuted Muslims hardly get attention, except in general human rights reports. On 5 December 1994, hundreds of young Muslim teachers were arrested in different parts when Eritrea broke off diplomatic relations with Sudan. The Eritrean government then accused Sudan of arming and supporting Islamist Eritrean opposition groups to operate from Sudan. A prison guard who defected from the regime reported in 2013 that those detainees were extra-judicially executed in May 1997.

In 1999, I visited Mensura, a village approximately 30 km north of Agordat, for research purposes. I was taken aback to find a bar directly adjacent to a khalwa, a place of religious instruction. It seemed that the bar had encroached upon the khalwa, rather than the other way around, in a community predominantly Muslim. Children were mere metres away from the bar, witnessing drinking and other inappropriate behaviour. Surprisingly, even the town’s administrator, who bore a Muslim name, and the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) he represented, showed no regard for such religious institutions.

By the end of 2017, a 92-year-old veteran Eritrean activist, Sheikh Musa Mohamed Nur, defied the regime’s interference in an Islamic school in Asmara. Following that, the first public civilian demonstration since independence took place in the city. Sheikh Musa died in Prison three months later, and all those young men who attended his funeral were arrested for years.

Over time, population dynamics evolve, making exact numbers less significant. In Eritrea, communities like the Bilen demonstrate religious harmony, with Christians and Muslims often coexisting within the same family, showcasing religious tolerance. Despite varying levels of religious knowledge, societies remain deeply rooted in their faith. Although the landscape has changed, khalwas continue to exist, more commonly in rural areas than in urban settings. In some European countries, Quranic teachings are now conducted through platforms like Skype or Zoom. I will always be grateful to Syedna Abdella for imparting the fundamentals of reading and writing to me.