Saturday 14 September 2024

What caused the Somali civil war?

The Somali civil war, which started in the 1990s, has given birth to varied scholarly arguments about what caused it. Hassan Mudane surveys some of the literature.

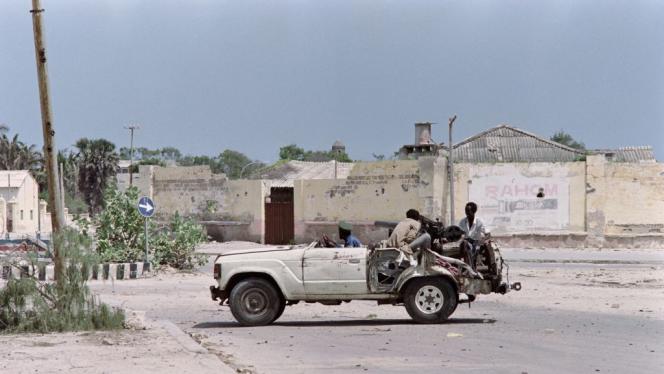

The Somali civil war was a brutal ordeal, causing state collapse, a huge outflow of refugees, significant loss of life, widespread damage to infrastructure, famine and multiple abortive attempts by foreign powers to reinstate and rebuild the government in Mogadishu. Somali writers, novelists, academics, and intellectuals have been intensely focused on analysing the events that led to the civil war, exploring how it became possible for Somalis—often considered a homogenous population—to turn against one another in a frenzy of mass violence which destroyed the country’s infrastructure, its state and tore apart its society leaving only memories of a lost world.

The Somali civil war has broadly speaking gone through four phases; (1) conflict between the government and armed resistance groups; (2) as the central government’s power waned and after its collapse, conflicts were more localised and clan based; (3) the factional clan based fighting became the new norm leading to the rise of warlords across the country; and finally this era which has two distinct phases. In the early 2000s, the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC) wiped out the warlords and then the federal government re-emerged to fight a UIC splinter group, al-Shabaab, with an international coalition.

Scholars have seriously deliberated its origins, considering everything from economic arguments to extreme repression and failures at Somali attempts to modernise. In this essay I plan to map out some of the major arguments and themes in their analyses separating them into those who put the clan at the center of their thinking and those who primarily attribute the violence to the broader context.

The primordialist explanation

Primordialists believe that the Somali civil war was primarily driven by conflicts between Somali clans. I.M. Lewis, a doyen in the field of Somali studies, exemplifies this perspective, as his analytical approach in general places the clan at the centre of Somali political life. In his seminal 1961 ethnographic study of Somalia’s northern regions, A Pastoral Democracy, Lewis outlines his approach. He contends that the clan is an organic defining feature of Somali society, and that these clans tend toward belligerent relations with one another. This, he argues, is the broad context within which Somali society should be understood and the political is downstream from this essential feature. In his work on the Barre regime, Lewis would maintain this viewpoint examining how Barre picked allies and stacked his administration with members of allied clans and would frequently use the term MOD (Marehan, Ogaden, Dhulbahante) to describe the constituencies from which Barre drew support.

His view is shared by other scholars, such as Said Samatar and David Laitin, who, in 1987, published Somalia: Nation in Search of a State. This book similarly seeks to situate the centrality of clans within the context of an arid and harsh environment, where camels and kin are the primary sources of power, influence, and prestige.

Samatar and Laitin trace the relationship between the clan and state authorities from the colonial era through to the emergence of an independent Somali republic in the 1960s, and continue through the period of the military regime, the eventual collapse of the state, and the subsequent rise of clan fiefdoms and warlordism. Somalis they argue do constitute a nation in the sense that they’re very self-conscious of their shared language, faith and customs. However, the proliferation of political parties in the early 1960s where Somalis had “more parties per capita than any other democratic country except Israel” illustrated the challenges of making representative democracy work in the nascent republic stratified along patrilineal clan lines.

Siad Barre’s military regime came to power in 1969, aiming to reduce the importance of clans and forge a more cohesive nation by amplifying nationalist sentiment in the country through the use of radio, newspapers, the development of a Somali script, and the construction of external enemies of the Somali nation. However, after significant setbacks – mainly the abortive attempt to annex the Ogaden region in 1977 – Barre reverted to manipulating clan politics to shore up his frail regime and compensate for his diminishing legitimacy. He eventually faced several clan-based armed groups such as the Somali National Movement and Somali Salvation Democratic Front which contributed to weakening his government before it eventually collapsed in Mogadishu.

Both arguments intuitively make sense to many but fail to consider several important points about how clan-based discourses are mobilised to make political demands and in I.M Lewis’ case ignore the impact of the colonial context in which he was studying Somalis. Clan loyalties also don’t directly determine political decisions, given Barre faced opposition from clans which some of his allies had close kinship ties to – the SSDF being an example.

When Lewis was producing his study, he was a part of the colonial administration in British Somaliland, and so the epistemic approach he employed was linked to his own positionality as someone thinking about how to make Somalis governable. Though British colonial rule was broadly indirect in the north and relied heavily on intermediaries and Somali collaborators, it codified and formalised Somali customs – xeer – and “changed what had always been highly contextualised and customised applications of Somali constitutional principles” write Lidwien Kapteijns and Mursal Farah. The payment of blood money (diya) is an example Kapteijns and Farah highlight, which they contend rose to the level of legalised collective punishment for people linked to a diya paying group, if they were linked through clan to a suspect. This didn’t involve serious investigations about the suspect or a fair trial. Kapteijns and Farah conclude that: “Lewis's work represents the late colonial consensus about what pastoral politics were all about” and not necessarily a reflection of lived social realities of Somalis. He doesn’t explore the impact colonial rule had on the relationship between the political and the clan and how Somali clans related to each other.

In the case of Said and Laitin, they assume that clan identity and clan differences necessarily lead to conflict but do not sufficiently explore the motivations of clan-oriented political elites and why they politicise clan identities in pursuit of their goals. Examining the extremely repressive political environment which snuffed out the prospect of parties with different ideas emerging could also have provided great analytical value for understanding why some groups reverted to the mobilisation of their clansmen to oppose the Barre regime. They also presume the fixed existence of a homogenous Somali nation similar perhaps to what members of the Russian ethnic group are to the Russian state or what Dutch are to their republic which warrants some scrutiny. In their view, Somalis failed to overcome the challenge posed by their decentralised social system and cohere into a modern nation which transcends that. But was this ever a realistic possibility?

Abdi Mohamed Kusow’s 1994 paper, The Genesis of the Somali Civil War, goes further into this theme, reaching a logical yet radical conclusion: that Somalis are not truly a nation in the conventional sense. He states: “despite the well-elaborated mythology about the culture, uniqueness, and the origin of the people, there was no such thing as the Somali people before the second half of this millennium.”

Kusow argues that scholars have focused on the division of Somali territories among various empires and its impact on the Somali body politic, rather than considering the “origin and formation of these clans” and “how they came to acquire their identities.” He suggests that this reluctance to address the foundational questions made the prospect of preparing for a potential civil war in Somalia remote even though it was always a possibility.

Expressing his dismay, Kusow writes: “This portrayal of the Somali nation has painted a picture for students of Somali studies and for Somali experts in which the slightest hint of a civil war remained inconceivable. Yet, Somalia is currently experiencing one of the worst civil wars in Africa.”

Kusow does not claim there is no Somali nation but argues that contemporary Somalis speak a variety of languages, usually categorised as dialects, which in some cases differ as much as Spanish and Portuguese. Somalis also have “elaborate” constructed histories with varying genealogies and differing socio-economic habits. These divisions, especially between the Darood and Hawiye, the two largest clans, came to the fore in the early 1990s, he argues. Kusow’s prediction about a future Somali polity based on his analysis was prescient: “Somali nationalism is fading and that [a] future Somali political organisation will be based on regionalism and clannism.”

While Kusow’s different approach to this question provides great insight into divisions among Somalis and the difficulties of reconciling those issues, he does not explore or explain why political ideas were not the main vehicle through which armed groups from marginalised clans revolted. The existence of the clan presumes a kind of inevitability about its politicisation, but the fact that Somalis in the past rallied under the banner of Islam demonstrates that politics can be done outside or without the clan at its centre.

The instrumentalists

Instrumentalists do not assume that the existence of clans necessarily leads to conflict. Instead, they focus on why clans were used as units for articulating political demands. Leading Somali scholars, Abdi Samatar and Ahmed Samatar, reject Lewisian or primordialist explanations of the Somali civil war.

Ahmed Samatar published several studies about the Somali civil war, arguing that I.M. Lewis confused kinship relations with clannishness (Ahmed Samatar, 1988). Following the civil war in 1991, many of his books and articles attempted to explain its causes. In their book, Somalia: state collapse, multilateral intervention, and strategies for political reconstruction, Ahmed Samatar and Terrence Lyons (1995, pp. 100-104) claimed that the underlying factors responsible for the Somali civil war are “the disintegration of political institutions and the resulting chaos and insecurity.” The absence of the state in an uncertain and chaotic environment, they argue, forced Somalis to return to kinship ties as the only form of social insurance and provider of safety.

Abdi Ismail Samatar, a veteran scholar and politician, who has extensively studied the importance of leadership for public outcomes holds Somalia’s political elites responsible for the violent civil war. In his 1997 paper, Leadership and Ethnicity in the Making of African State Models, Ahmed Samatar contrasts the differing approaches to governance between elites in Somalia and Botswana, illustrating how these approaches have led one country to become a symbol of state failure and the other a stable and wealthy democracy. Both countries, he argues, are tribal and clan-based, but the leadership in Botswana, particularly under Seretse Khama, guided their society away from parochial politics. “The unity of the elite, the legitimacy, consciousness, and discipline of its leadership play a vital role in creating social conditions which foster positive political and economic environments in Botswana,” writes Samatar.

In contrast, Somalia’s mismanaged state institutions and collective resources led to a social breakdown that “reversed voluntary trends of national integration.” Samatar suggests that the larger structural breakdown of the state allowed short-sighted political entrepreneurs to exploit the circumstances to enhance their own standing: “Facing such lawlessness and chaos, people had to find protection in the shadowy structures set up by the new lords of Somalia’s Bantustan-like homelands, thus falling prey to various ‘tribal’ traps set up by the victorious factions of the elite.” In Samatar’s view, the Somali public are victims of this situation and not active participants, described as a “disorientated population who desperately need socially responsible leadership.”

The American political scientist Ken Menkhaus similarly examines the actions of leadership figures, closely analysing their motivations. In his 2003 paper, State Collapse in Somalia: Second Thoughts, Menkhaus outlines the limits of approaching their motivations through the lens of the political economy of war, arguing there are “not many Somali players who clearly benefit from complete state collapse.” He writes: “The 'war economy' theory is thus of real use in explaining part, but not all, of the Somali debacle.” Menkhaus takes a more complex view when assessing what was blocking a resolution to the Somali civil war, categorising the obstacles as follows: individuals or clans “not satisfied with their share of the pie”; what he calls “intrinsic spoilers,” who benefit from the anarchy and lawlessness; and actors whose opposition is “driven by risk-aversion”—groups and individuals who may benefit from peace but “choose the suboptimal but safe route of scuttling initiatives which might alter an operating environment.” Menkhaus’s view offers more nuance than simply concluding that the existence of clans necessitates conflict, adding several caveats.

Abdulahi A. Osman’s 2007 intervention, a belated response to Kusow’s argument about the risks inherent in Somalia’s diverse make-up, examined the material factors that created the conditions under which Somalia’s clans declared war on one another. Like Kusow, he recognises that clans have very distinct identities which can erode solidarity among Somali peoples, as clan identities take precedence. However, he does not assume that this is inevitable. “The conflict was initiated by clans who cited the existence of an inequality that preferred certain clans to others,” he says. This inequality created grievances that were exacerbated by economic inequality in the country, poor economic performance, and the widespread availability of arms.

Afyare Abdi Elmi and Abdullahi Barise similarly look at the broader factors, citing “competition for resources and power, repression by the military regime and the colonial legacy” as the background causes of the conflict. The conflict, however, wasn’t driven by clans per se, but was intensified when clans were politicised. They also echo the ideas of Osman, explaining that the availability of arms and “the presence of a large number of unemployed youth have exacerbated the problem.” Both Elmi and Barise’s paper and Osman’s report that arms began to fall into the hands of the public as Somali society was militarised through the 1970s and to a dangerous extent in the 1980s, as economic decline and high inflation led to leakages of arms to the public. The failed Ogaden war was also a major contributor to arms proliferation. However, neither fully explains why the conflict didn’t begin in the 1980s instead of the 1990s.

In his 1996 book, From Bad Policy to Chaos in Somalia, Jamil Mubarak examines how the Barre regime’s economic strategy and its management of the decline in the 1980s were detrimental to national development. This mismanagement caused the country’s economy to deteriorate, eviscerating its fiscal viability and eventually contributing to state collapse and civil war.

Abdi Dirshe straddles the line between the two camps. He recognises what he calls “clan nationalists” as being partially responsible for the breakdown of the Somali state, but attributes a larger share of responsibility to “the colonial institutional legacy” and the introduction of neoliberal economic policies, which economically emasculated the Somali state.

Christopher Paul, Colin P. Clarke, Chad C. Serena, and Mohamed Haji Ingiriis all advance the view that it was the conduct of the Barre regime and its authoritarian governance that pitted clans against one another and laid the groundwork for its eventual implosion, leading to mass violence in Somalia. Paul, Clarke, and Serena, in their book on ungoverned spaces and drug trafficking, argue that the government created “competition for resources in an already resource-scarce environment,” thereby incentivising violence. Ingiriis, in his book on Somalia’s military regime, The Suicidal State in Somalia, examines how African dictators in general, and Barre in particular, ended up recreating and mimicking colonial-era dynamics in their own societies, often brutally dominating them. This led Somalia from being what he calls a “clannised state” to a “criminalised state” which had a predatory relationship with its own population. That they rose up against Barre’s regime, he contends, was a natural reaction given the circumstances.

While Ingiriis raises several important questions about the nature of the Somali state, Florence Ssereo goes a step further by asking whether the Westphalian model of the state, which Somalia adopted after independence in 1960, and the failures with modernisation, led to the Somali civil war. According to Ssereo, to understand the current political crisis in Somalia, we need to examine the process of decolonisation and the formation of the first and second republics of Somalia.

This article is a summary of Hassan Mudane’s master thesis which critically examined the scholarly literature on the Somali civil war.