Thursday 21 November 2024

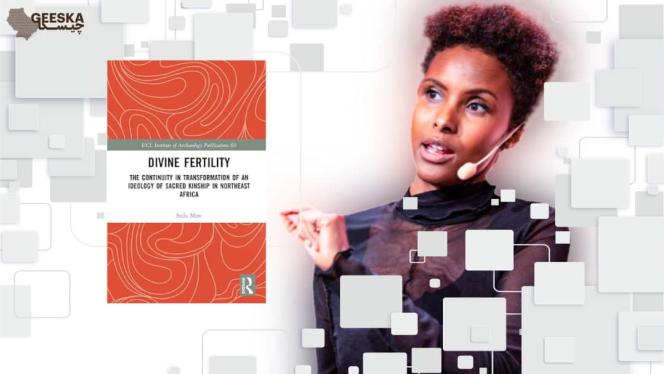

Unveiling sacred kinship: a review of Sada Mire’s Divine Fertility

The Horn of Africa today is deeply divided, both politically and socially. These divisions have led to widespread conflict and a belief, even among members of the same ethnic group, that our differences are irreconcilable. As a result, people often trace current issues back into the past, crafting elaborate tales of centuries-old feuds with groups they may not get along with. However, Mire’s new book offers a strong counterpoint to this centrifugal and violent trend, uncovering the threads that connect many of the cultures in the Horn of Africa region. “Geographical barriers are often nothing of the sort in real life,” she writes. For example, she contends that Cushitic people “root their kinship in their genealogical links to religious leaders.”

She also argues that a common belief in a singular Sky-God called Waaq predisposed the people of the region to Islam and Christianity. “They recognise God as an omnipresent being, and the saints and sacred ancestors as his representatives on Earth. And kinship is the medium through which they seek to connect with God’s prophets,” Mire reports.

Sada Mire’s Divine Fertility: The Continuity in Transformation of an Ideology of Sacred Kinship in Northeast Africa examines the influence of indigenous ideologies on the daily lives of communities in Northeast Africa. By delving into the region’s pre-Christian and pre-Islamic beliefs and practices, passed down through generations, the author challenges the prevailing political narratives that often oversimplify the cultural complexities of this area. Mire demonstrates that, for millennia, intricate indigenous institutions have served as a unifying force, transcending the boundaries of Christianity and Islam.

The book draws on the latest archaeological and ethnographic research to investigate the concepts, landscapes, materials, and rituals associated with the Sky-God belief system, a shared cultural heritage in the region. It sheds light on the connection between sacred fertility and various regional archaeological features, as well as enduring ancient practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM), spirit possession, and other physically invasive rituals, including hunting rituals.

It particularly explores the sacred landscape of Saint Aw-Barkhadle, a major Sufi pilgrimage centre in Somaliland, believed to have been established in the 12th century AD. This site, reputed to be the burial place of the early rulers of the Ifat and Awdal (1285–1402) dynasties, and possibly even the lost first capital of the Awdal (Adal) kingdom before Harar, is presented as a ‘microcosm’ of the ancient Horn of Africa with its diverse multi-religious heritage.

Mire’s interdisciplinary approach is both ambitious and innovative, as she moves beyond the specific case study of the Aw-Barkhadle shrine to argue, based on archaeological findings, for the extensive influence of an Eastern Cushitic ritual complex centred on fertility. However, the broad scope of the book introduces challenges in balancing the construction of a grand narrative with the need to present the primary data supporting it. Despite these challenges, the core of Mire’s work offers invaluable new insights, especially in areas that would be inaccessible without her unique linguistic capabilities and cultural understanding. This review will adopt a critical stance towards certain aspects of the book while crediting the substantial contribution it makes to its field.

In the introductory section, Mire offers a well-reasoned rationale for the study, followed by a concise two-page “About this Book” section. Chapter 1 sets the stage by outlining the study’s aims, objectives, theoretical underpinnings, and methodology, while also providing essential religious context. The critical perspective presented is valuable, particularly in highlighting the lack of indigenous scholarship, the dominance of male-driven research, and the persistence of colonial legacies. Mire aptly notes that “African archaeology appears, currently, to make little use of any anthropological research into the issue of rituals in the past and carries out even less of its own anthropological research into this topic in contemporary society.” However, the book’s approach to the past through an ethnic lens, particularly its use of the term “Cushitic,” is problematic. These terms, though applied broadly in the study, could be misappropriated in contentious contexts, such as land claims or heritage disputes in areas with active ethnic tensions, as seen in regions like Ethiopia.

Nonetheless, the assertion that territories like Aksum were likely more extensive than traditionally depicted, extending further east, is credible and supported by recent research in eastern Ethiopia. This research suggests ongoing connections with the northern highlands, the heartland of the Aksumite kingdom.

Chapter 2 delves into the Sufi centre of Aw-Barkhadle, where the conversion of northern Somalis to Islam took place in the 12th century, and its surrounding landscape. Here, Mire presents significant new data that highlights the ecumenical cultural complexity of the region. Notably, gravestones marked with Coptic crosses and Stars of David suggest the presence of both Christians and Jews in the Aw-Barkhadle area. Additional evidence is mentioned more informally, such as the author’s reference to images of small, hand-shaped tablets engraved with the Star of David, Menorah, and other symbols.

Chapter 3 continues exploring the Aw-Barkhadle sacred landscape, focusing on material culture, fertility, and sacrifice. While the chapter offers valuable information, some aspects could benefit from further elaboration. For instance, the comparison between Muslim gravestones at Aw-Barkhadle and stelae from Aksum, based on their four-cornered shapes and soft edges, seems tenuous. Similarly, the discussion of drums and their cultural significance would be strengthened with more thorough referencing to fully explore their relationship to African traditional drum culture. An intriguing section on fertility stones and their uses is also included, though the presentation occasionally feels disjointed, with material sometimes appearing out of context. For example, a quote from Canadian anthropologist Christopher Hallpike’s study of the Konso of southern Ethiopia could be misinterpreted as suggesting that all priests used phallic roof pots, rather than this being specific to Konso priests as the original context implies.

Chapter 4, which examines divine kinship through the lens of fertility, is arguably the most successful part of the book. Mire provides original, detailed, and well-contextualised data on Somali women’s fertility rituals, with the discussion of the wagar, a wooden object associated with the belief in sacred trees, being particularly noteworthy. The author’s personal connection to the wagar, having inherited one from her maternal grandmother, adds a unique and compelling dimension to the analysis.

Chapter 5 continues the exploration of fertility by examining Sufism and indigenous, or “Cushitic,” institutions. However, the archaeological discussions in this chapter require further expansion. For example, the port of Zayla has been the subject of archaeological investigations by French and Spanish researchers (e.g., Fauvelle-Aymar et al.; González-Ruibal et al.), yet these findings are not mentioned, despite their potential to enrich the argument.

In Chapter 6, the discussion broadens to encompass the “ideology of fertility in the archaeology of the Horn of Africa”, where Mire introduces and develops her concept of the “Ritual Set.” This is described as “a set of material and non-material manifestations and attributes which uses specific examples to shed light on the investigation and (re)interpretation of archaeological material and sites in the region”. However, the reliance on ethnographic analogy as the basis for the “Ritual Set” presents a challenge, as this method is difficult to apply consistently. Additionally, the variability among the Ethiopian sites discussed—Tiya, Aksum, Lalibela, and the Sheikh Hussein shrine—poses another issue. These sites, though located within the Horn of Africa, are contextually and chronologically distinct, making it problematic to subsume them under a single Cushitic interpretation without acknowledging the specific contexts in which they developed. For example, the meanings ascribed to the stones in these sites may be far more diverse than the reasons outlined in the book.

Chapter 7, though spanning only two pages in a 329-page book, may seem brief but succeeds in providing a concise summary. It concludes on a reflective note, proposing that indigenous Sky-God beliefs did not clash with Christianity and Islam but rather complemented them, allowing people “to offer up sacrifices and worship God in the interests of peace, prosperity, and fertility”.

Dr Sada Mire has emerged as a prominent figure in the study of the archaeology and heritage of the Horn of Africa, with a particular focus on Somaliland. This groundbreaking study of sacred landscapes, tablet traditions, and ancient Christian and medieval Muslim centres in Northeast Africa represents a landmark effort in creating a theoretical and analytical framework for interpreting the region's shared heritage and indigenous archaeology. This work will undoubtedly serve as an essential resource for archaeologists, anthropologists, historians, and scholars dedicated to the study of the Horn of Africa and beyond.