Tuesday 15 October 2024

What I’ve learnt telling Somali diaspora stories

Photographer and storyteller Mohamed Mohamud reflects on nearly a decade of documenting the stories of the worldwide Somali diaspora.

Diasporas exist for a variety of reasons. Some people migrate in search of economic opportunities, others leave their homelands due to persecution, while empires can facilitate movement within their territories. In other cases, natural disasters, famines and droughts force communities to flee. So where does the Somali diaspora story start?

Though seafaring Somalis have travelled the world for centuries, the modern story of the diaspora begins in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when insurgent movements overwhelmed the central government, eventually causing it to collapse, pulling everything with it into a violent abyss. Burburka (the destruction) is how we describe the experience.

In the early 1990s, as the war began, the global Somali diaspora numbered fewer than a million people (with estimates at around 850,000). By 2015, that figure had risen to nearly two million, with major communities in the US, UK, Scandinavia, the Gulf countries and other places across east Africa. Some Somalis cut against the grain and settled in places like Indonesia, Pakistan and China.

By 2015, that figure had risen to nearly two million, with major communities in the US, UK, Scandinavia, the Gulf countries and other places across east Africa.

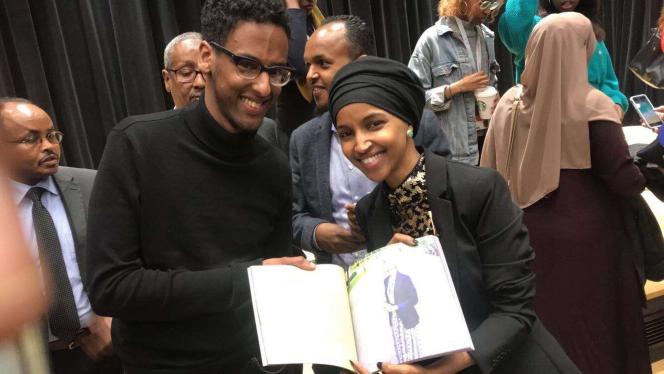

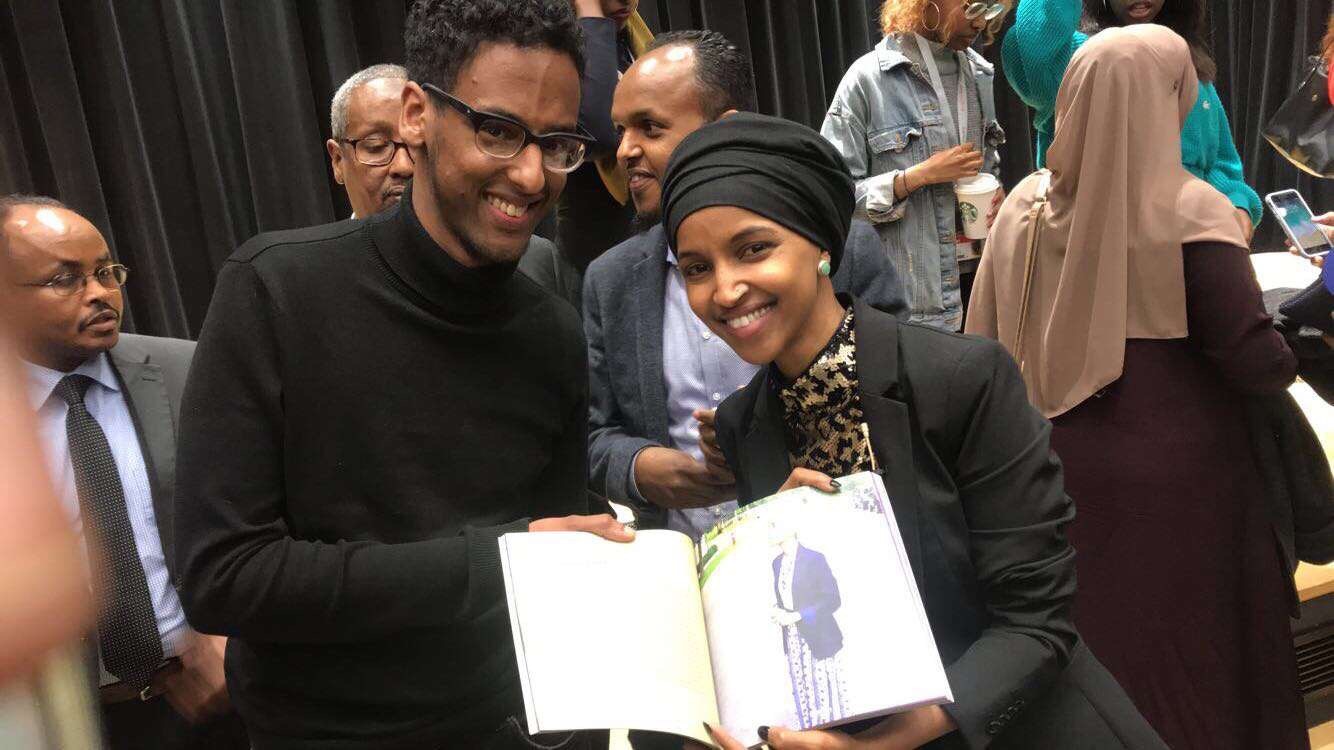

Although the journey from being a refugee community to emerging as a cultural force has been far from smooth, a few members of our diaspora have become some of the most recognisable faces of the age. Ilhan Omar is a globally renowned politician; after starring in Captain Phillips, Barkhad Abdi rose to Hollywood stardom; and Mo Farah exceeded all expectations with his extraordinary performances becoming the most successful British Olympian in history.

I’ve spent much of the last decade documenting the stories of this global community, travelling to visit Somalis in any country where I can find them with my camera and notebook.

My travels provided profound insight into how Somalis have managed to maintain a coherent cultural identity while integrating into their new homes. During my journey, I witnessed the resilience, entrepreneurial spirit, and strong sense of community that characterise the Somali diaspora, yet I also observed how experiences can vary greatly depending on one’s specific local context.

One of the common aspects shared by every Somali community I visited was their enduring connection to the old country. These communities are scattered across the globe, and their close contact with the homeland is largely maintained through remittances. Remittances serve as a lifeline for many families back home, and a significant part of Somalia’s economy depends on the money transferred from overseas. The International Monetary Fund estimates that Somalis send on average $1.3 billion annually.

Though debates on the “black tax” have been reignited online, everyone I spoke to, from small business owners in Nairobi’s Eastleigh to professionals in Canada and students in Germany, discussed this collective responsibility towards their relatives in Somalia. Statelessness has forced Somalis abroad to become the social safety net for relatives and friends back home. This shared commitment reflects a strong pledge within the closely knit structure of Somali society, where, despite the physical distances separating them, family and community ties remain robust.

Though debates on the “black tax” have been reignited online, everyone I spoke to, from small business owners in Nairobi’s Eastleigh to professionals in Canada and students in Germany, discussed this collective responsibility towards their relatives in Somalia.

Of course, there are significant differences between different communities; however, the similarities stand out. One notable aspect is the Somali entrepreneurial spirit. Scholars of ethnic employment among migrant communities list two major reasons for why these people turn to self-employment; the first is blocked social mobility which makes entrepreneurship a necessary means for individual and communal survival; the other is that some communities benefit from a culture of entrepreneurship. Somalis appear to have both, developing “ethnic economies” which serve our community so that we build and rise together as a response to marginalisation but also because trade is such an important feature of our culture.

From the bustling markets of Eastleigh in Kenya to small businesses in Minneapolis, USA, and thriving enterprises in South Africa and the UAE, Somalis have turned lemons into lemonade developing businesses which cater to the unique requirements of the community in the preservation of their faith and cultural identity. Globally, behemoths like Dahabshiil have largely emerged as a result of this. According to Forbes, “Dahabshiil now operates from more than 24,000 outlets across 126 countries and employs more than 2,000 people. The company had 2016 revenues of more than $1 billion.” Ismail Ahmed founded World Remit, another hugely successful company, in 2009 to solve money transfer issues too.

Whether in retail, real estate, or technology, the Somali diaspora is renowned for its resourcefulness and adaptability, which enable them to thrive even in the most inhospitable environments.

Another commonality among them is the emphasis on cultural preservation. In these communities, numerous activities are undertaken to maintain the Somali language, traditions, and religious practices. Cultural centres and mosques serve as vital places for upholding Somalinimo in London and Toronto, where the second and third generations of Somalis have grown up. Community leaders often play a crucial role in educating the younger generation about Somali history, literature, and values to ensure that their culture is preserved amidst the pressures of assimilation.

In western countries the War on Terror, as well as the broader seductiveness of discarding what we inherited from our parents is appealing. But far from ceding ground, young Somalis have broadly turned the tables, with Somali words entering the popular lexicon, particularly in UK hip hop and grime. In a piece about the growth of the UK Somali music scene, Abubakr Finiin wrote that the “The Somali sound is now louder than ever in the UK.”

Far from ceding ground, young Somalis have broadly turned the tables, with Somali words entering the popular lexicon, particularly in UK hip hop and grime.

The western world is only a small part of the global Somali diaspora, however. The largest Somali communities remain in neighbouring east African countries.

Although circumstances have changed for Somalis with Ethiopian citizenship under ethnic federalism, they still face marginalisation from the political and economic mainstream in the country. In Kenya, the situation is more mixed, with an indigenous Somali community that has historically faced persecution from local authorities suspicious of their connections with the republic. This community has since grown in stature and wealth, exercising significant economic and cultural influence in Kenya today.

Other Somalis live in uncertain conditions in refugee camps where they have resided since the government collapsed, establishing significant refugee cities. Aamna Mohdin, a correspondent for The Guardian, recently chronicled her own experience of moving from Kakuma to the UK and then returning, describing it as the “foundation” of who she is.

One of the important lessons I gained from my trips is how much the Somali diaspora communities can learn from each other. For example, the Somali community in the Netherlands, which has been better integrated, offers valuable insights into how policies related to education and employment facilitate better integration.

The higher levels of political involvement among Somalis in the US and Canada serves as an excellent example for other Somalis, highlighting the importance of amplifying their voices in the countries where they reside. Ahmed Hussen in Canada for example has served as an MP since 2015 and is now a member of Justin Trudeau’s cabinet as his migration and resettlement minister. In the US, at least 25 Somalis have been elected to represent their communities at the local, state and federal level since 2016, with Somali women really trailblazing.

The experience of coalition building and representation in local governments has demonstrated how civic engagement can shape policies that benefit the diaspora.

What would be incredible to see is these communities linking up more, particularly in the fields of commerce where there is great potential. For instance, UAE-based Somali entrepreneurs could provide guidance and support to businesses in South Africa or east Africa to help them overcome economic adversities and penetrate global markets.

What would be incredible to see is these communities linking up more, particularly in the fields of commerce where there is great potential.

My journey across Somali diaspora communities reaffirmed the strength and resilience of the Somali people. Each community faces its own unique challenges given the local context, but there is a determination to overcome obstacles and engage constructively in both the host country and Somalia. The remittances sent back home remain symbolic of that relationship, but the real story lies in how these communities thrive and adapt.

In this regard, Somalis from around the world can support one another and share solutions to common problems while continuing to build a global network bound by a shared identity and a vision for a better future through increased dialogue and interaction among these communities. The Somali diaspora has already demonstrated how to turn adversity into opportunity; the next step is learning from one another to build even stronger and more cohesive communities worldwide. Initiatives like the Global Somali Diaspora which was held in Istanbul this year help move us in that direction.

The Somali diaspora has already demonstrated how to turn adversity into opportunity; the next step is learning from one another to build even stronger and more cohesive communities worldwide.

I began my own journey into this world with the goal of capturing knowledge and exploring these stories through Somali Sideways, which I founded to help amplify Somali voices and counter negative stereotypes. Somali Sideways has transformed into a venue for visual storytelling, showcasing the everyday experiences of Somalis around the world. I soon learned that migration has shaped the identity of Somalis in remarkable ways.

My journeys took me to lesser-known Somali communities, such as Jakarta, Indonesia, and China, giving me a broader perspective on the Somali diaspora. Most Somalis in China, for example, come to pursue university degrees, particularly in subjects like medicine and social sciences, as tuition fees are lower in China than in Europe or North America. I then met Abdulla Farah, a Somali living in Qatar who was studying at Nanjing Normal University. Abdulla recognised me instantly from Somali Sideways, and we exchanged contact details and have kept in touch ever since. I also met several other friends, including Hanad from Hargeisa, Somaliland, who is studying the Chinese language at Xiamen University.

I spoke with her at length about the feelings one experiences while living in an unfamiliar environment. She told me: “My view completely changed when one of my sisters went to China for her studies. The way she narrated her experiences transformed my perceptions and painted a picture of a country in vibrant colours that many dream of calling home.”

She expressed her gratitude for having been a beneficiary of the scholarship provided by the China Scholarship Council, courtesy of the Somaliland government. “I was pleasantly surprised to find that my experiences exceeded all expectations in every possible way,” she said of her time in Nanjing. She added that the city is a “unique blend of ancient traditions and modern living, coupled with the friendships I formed and the knowledge I gained, and has left an indelible mark on my heart and mind.”

Dr Hamdi was a friend on social media for many years until December 2021, when I visited Cairo, Egypt. Hamdi graduated as a medical doctor in 2023 from the Faculty of Medicine at Ain Shams University. I had informed her that I was visiting the city and would be hosting a book event at The American University in Cairo. Unfortunately, we did not get a chance to meet. However, she said, “I was out of the country, and while I could not attend myself, I did my best to call others who could, and they attended on my behalf. Needless to say, it was quite a success.” Events like these, she added, bring the community together and “keep us moving ahead. They encourage us to pause for a moment, embrace each other, and learn from one another.”

Dr Hamdi had been following Somali Sideways on social media since its launch, and she describes it as “a pillar for our community, even without us realising it. Over the years, witnessing how Mohamed has crafted a piece of art like this and continues to push forward has inspired many of us in the diaspora, me included, to take initiatives and strive to make a difference.”

These are some of the lesser-known communities, each as impactful as those in North America or Europe. Somalis in China are primarily students and businesspeople seeking to bridge cultural gaps for themselves and their families. Somalis in Jakarta are part of one of the smallest communities in Southeast Asia, tackling life with the same entrepreneurial drive that characterises others across the diaspora. However, in Jakarta, I have been informed that there are many refugees and asylum seekers living in the country; in particular, Somalis constitute more than 10% of the population, coming behind Afghanistan and Myanmar. Many of them use Indonesia as a transit point to their destination, most notably Australia, but some remain in limbo.

Somalis in China are primarily students and businesspeople seeking to bridge cultural gaps for themselves and their families. Somalis in Jakarta are part of one of the smallest communities in Southeast Asia

The thing is, with Somali Sideways, I have been able to capture not only the resilience and adaptability of these communities but also the profound impact it has had on their lives. Migration has enabled Somalis to spread their culture, contribute to local economies, and maintain strong ties to Somalia. However, it has also presented new challenges, ranging from navigating foreign education systems to facing xenophobia in places like South Africa, Europe and North America. What they all have in common, though, is a shared sense of responsibility to Somalia through remittances, community support, and a deep longing to stay connected to their roots.

These stories and encounters made me realise how varied the experiences of Somalis are, shaped by different conditions in their host countries, yet united by a strong determination to succeed and retain their identity. Somali Sideways has become a platform to showcase those stories and transform the narrative of migration into one of resilience, success, and the positive contributions that Somalis make globally.