Thursday 21 November 2024

Abiy believes in the myth of his own indispensability, says Tom Gardner

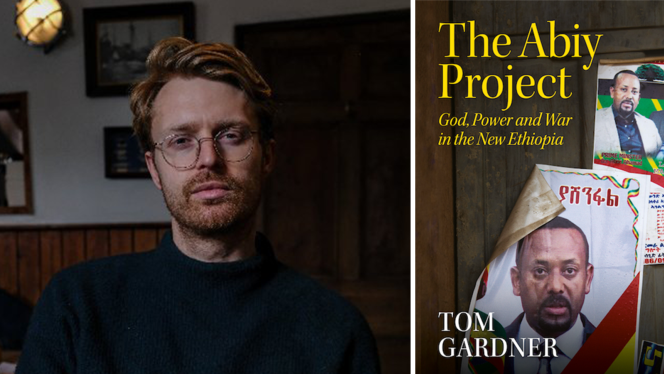

Tom Gardner, the Economist’s Africa correspondent speaks to Geeska about Ethiopian politics and his new book on the “Abiy Project”

When Abiy Ahmed came to power in 2018, the political tremor caused by his rise sent its shockwaves throughout the region. Then 42, Abiy was Africa’s youngest leader and Ethiopia’s first to identify as Oromo. All eyes were on him as he promised deep reform, vowing to take Ethiopia in a new direction domestically and in its foreign relations.

A resident of the capital, speaking to Tom Gardner, then reporting for the Economist from Addis Ababa, drew parallels between Abiy’s rhetoric and the lofty tones of Barack Obama.

Abiy set the bar extremely high and measuring anyone against that yardstick would have them wanting in the most favourable of circumstances, and they certainly weren’t favourable. “The Ethiopian state was basically crumbling before he took charge in 2018,” says Gardner. The ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) was facing persistent protests and violence in several regions and though growth figures looked good on paper (it was the fastest growing economy in Africa then) those benefits didn’t accrue to large parts of the country.

His efforts were further complicated by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Trump administration’s lack of interest in Africa, and the broader turbulence of a region grappling with conflict, climate crises, and political instability. But 6 years on, and many journalists and analysts now view Abiy in a very different light. Conflict has spread further in Ethiopia, with many expressing concern about the general direction of the country under his leadership.

Tom Gardner, based in Africa since 2016 (many of which were in Ethiopia), has been tracking Abiy’s premiership since he came to power and has compiled his observations in an upcoming book: The Abiy Project: God, Power and War in the New Ethiopia. Gardner, now the Economist’s Africa correspondent, speaks to Geeska about Abiy’s rise, his leadership style and why he chose to write a book about him.

Faisal Ali: Why a book about Abiy Ahmed, and not wily old Afwerki, who’s been around longer, or Uhurru Kenyata whose own political demise had big implications for Kenya?

Tom Gardner: Well I was based in Ethiopia, and so for obvious reasons, I was rather more qualified to write about Abiy than any other leader in the region. If we look at the other leaders though, Isaias [Afwerki] has been written about to some degree. Uhurru Kenyatta is a significant figure in 21st century African politics, undoubtedly, but the contention of my book is that there is no politician quite like Abiy in terms of his impact, not just on Ethiopia but the region. He has upturned the established order, taking a sledgehammer to institutions which have ruled the country for almost three decades. I also believe he will come to be seen as the defining African leader of the multipolar age.

FA: Was there anything in Abiy Ahmed's early life that surprised you when researching this book?

TG: I do see a striking continuity in some of the ideas and themes which have shaped his political thinking which go back a long time, to the early 2000s. The prosperity gospel for example, that mindset and individual agency can transform countries, that poverty is a state of mind. These are contentious ideas. Abiy’s critics often say he doesn’t really have beliefs; that he’s purely opportunistic or cynical and says whatever will win the room on any given day, so it struck me how far back in his biography these recurring themes were present.

FA: Abiy Ahmed emerged initially as this energetic reformer. He apologized for torture, increased female and minority representation in the cabinet, made peace with several rebel movements, set up a human rights commission, won a Nobel Prize, began privatization of key sectors of the Ethiopian economy, and also reportedly denounced the ‘godless’ Chinese Communist Party in private discussions with American officials, despite China being a major economic partner for Ethiopia. He wasn't just singing from the right hymn sheet; it was a celestial performance that left many dazzled. People termed this phenomenon ‘Abiymania’. Things eventually turned out differently at home and abroad. This has led people to wonder if he was just a really intelligent manipulator, plotting a course that would allow him to win support and deal with his opponents lethally, or someone who had sincere ambitions but got bogged down by the undead ghosts of Ethiopia's past he wanted to dispel. What is your reading of him?

TG: I was witness to the euphoria and probably played my part in popularising the term. It was a very accurate term, at least in Addis Ababa, Amhara and Oromia at the time, in terms of the mood. In my book I have a chapter on this period, and I try to recreate that.

To what extent was that an act or a mask covering his true intentions? That is the central conundrum of the Abiy project. I would argue that to an extent both are true. He believes himself to be sent by God. He clearly sees himself as indispensable to the fate of the nation and he definitely has a vision. It isn’t a clear ideological program; perhaps it’s more a notional idea of where he wants to take Ethiopia. He wants to usher Ethiopia into a modern, prosperous and I would argue, post-ethnic future. A nation of God-fearing individual strivers. And if someone believes they have a providential destiny to realise their vision, that can potentially justify anything. That is where the cynicism, unwillingness to compromise and ruthlessness comes in. He has a certain flexibility with respect to the means but he is clear on his ends.

FA: Sometimes the best way to understand a political figure is to check his mentors. You mention Minase Woldegiorgis (Abadula). What was his relationship with Minase and what impact do you think he had on him?

TG: He was the leader of OPDO (Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation) and is the godfather of modern Oromo politics. He is the titanic figure in that party which dominated the Oromia region. He recruited significantly from the younger generation then, including figures like Lemma [Megersa], Shimbelis Abdisa and Abiy who are all the children of Abadula.

To what extent do we think of Abiy as an Oromo politician, that is where Abdaula really comes in. Abadula is a forerunner to Abiy in some regards, in that he is an Oromo nationalist, but one that is committed to the Ethiopian state and sees an expanded presence for Oromos at its heart. Abadula also was a key figure in trying to make the OPDO a key player in Ethiopian politics and not a junior partner. The project of emancipating the Oromo governing class from the TPLF starts with Abadula and is taken forward by Abiy and Lemma, with Abiy moving it in the direction of what appears to be a more conventional Ethiopianist nationalism.

FA: You’ve intimated that Abiy views himself as a kind of cross between a religiously anointed all powerful Ethiopian emperor & tech CEO. A cross between Tewedros and Bezos if you want. How does that differ his leadership style from his predecessors, Hailemariam Desalgn and Meles, and his peer, Afwerki?

TG: Abiy is a type of bricolage of all these influences which is why he is hard to pin down. It is an inherently risky enterprise. Abiy and Isaias recall the imperial Ethiopian monarchy. The running of a secretive court, dominated by intrigue and conspiracy and the ruthless disposal of enemies. Both Abiy and Isaias share that style.

Hailemariam is a more well-meaning technocrat, not a politician of the sort you need to be to flourish in Ethiopia and is very different from Abiy Ahmed in that regard. But Hailemariam was also a strong believer who believed he was doing God’s work, though he was careful not to break with the secular conventions of the ruling EPRDF. Hailemariam is also evangelical and pentecostal like Abiy Ahmed. So, they share that religious conception of politics. He might be thought of as a sort of John the Baptist figure to Abiy’s messiah, or that is how Hailemariam himself for a while seems to have seen it.

FA: The place of Islam in public is more prominent today in Ethiopia than any time I remember and though I don’t want to overstate the point as terrible human rights violations continue across the country, what are your thoughts on how he has handled this?

TG: Meles Zenawi dealt with the Muslim community through the lens of the War on Terror, so it was driven by a securitised approach and heavy-handed meddling. He wanted to impose an acceptable form of Islam which was more quietist. As for Abiy Ahmed, there are many question marks around his childhood, his father too but he did have an Islamic education growing up. He was very close to a prominent sheikh in his own town as a teenager, so he’s reasonably well-versed.

He converted to Christianity later after surviving an incident during the Eritrea border conflict. But he has a diverse religious upbringing, and is connected to all three of Ethiopia’s major faiths. His mother was Orthodox, his father Muslim and he’s Pentecostal. I think he sees religion in this regard as a tool for buttressing his political position by presenting himself as a unifier.

But he’s not a Pentecostal politician. Some in his religious community criticise him for that. Iftars have been held in Meskel Square which are important symbolically; Irreechaa too, part of the pre-Abrahamic Oromo traditional religions. So this is an interesting side note.

FA: Optics are really important for Abiy. The Ethiopian state has sleek corporate branding, everyone wears sharp tailored suits and Abiy likes to make it look like revolutions have occurred and are occurring in Ethiopia. But large parts of Ethiopia remain embroiled in fighting that preceded his reign, despite his vow to reconcile the country with itself. Fresh fighting started in Tigray in 2020 for example. Why has he failed on this count?

TG: Well it’s important to say the Ethiopian state was basically crumbling before he took charge in 2018. It was losing its monopoly on violence and the state needed to be reconsolidated. He needed to find a new answer to the fundamental structural problems which were manifesting themselves in different areas of the country for different reasons.

Abiy also believes in the myth of his own indispensability; that he has the answer to all of Ethiopia’s problems. That primarily starts for him with a new mindset, moving away from what he considers outdated ways of thinking. A large number of Ethiopians don’t see the country’s problems in the same way and don’t believe he has the magic bullet for the country’s problems. And starting with Oromia in 2018 they revolted. His professed solution has not proved sufficient.

But we’ve also seen that he hasn’t broken with the tradition of his predecessors of dealing with opponents, especially those which threaten his rule, through spectacular displays of overwhelming violence.

FA: In an incredibly strange turn, the Somali region of Ethiopia is now one of the most stable, whilst regions which determined the fate of Ethiopia (Amhara & Tigray) have become really unstable. How has the centre’s relationship with the Somali region and peripheries more broadly changed during the Abiy era?

TG: Well to draw you back to the contradictions again, this is one of them. Abiy is a centraliser and I think what Mustafa Omar has found is that if he submits to the central government he will be granted a significant degree of autonomy in how he governs his region; more autonomy than at any other point in the Somali state’s recent history. The role requires a degree of collaboration inherently and Mustafa is seen as Abiy’s man in the Somali region which has impacted his popularity but even critics conceded that it has stabilised.

Mustafa is a pragmatist. He’ll go along with Abiy’s demands when needed and doesn’t challenge his authority but he has simultaneously carved out space for himself to operate.