Thursday 21 November 2024

Somalis in Ethiopia: still outsiders looking in

On a recent visit to Addis Ababa, I accompanied my cousin to the Ethiopian Immigration and Citizenship Services Office in the Kazanchis area of the city—a trendy neighbourhood named after an Italian construction company. My cousin was there to apply for a yellow card, a residency permit that grants members of the diaspora certain privileges, such as exemption from entry visas and some restrictions applied to foreign nationals visiting Ethiopia.

At the first stage of the application process, her identity documents, authenticated by Jigjiga courts with their official seal, were presented to an immigration officer. Within seconds, the officer dismissed them as counterfeit. Right then and there, my cousin was accused of being Somali posing as Ethiopian. She was no longer considered a “Somali Ethiopian”—a contested term in itself—but was labelled as a “Somali Waryaa.”

This experience was instructive for me. For Somalis in Ethiopia, identity is a complex puzzle—a delicate balance of cultural pride, political caution, and survival within a state that has often viewed them with suspicion. It was no accident, for example, that the late Wallelign Mekonnen, a prominent Ethiopian Marxist and student activist, in his seminal attempt to address the question of Ethiopian nationalities, only grudgingly acknowledged Somalis as part of Ethiopia’s nations “however much” one might dislike it.

For my cousin, having fully authenticated documents and being from Qabridahar—a storied city at the heart of the Somali Region—meant little. What mattered most was the subjective judgement of her “Ethiopian-ness” by an agent of a system that does not regard Somalis as truly Ethiopian. Or at least, not Ethiopian enough.

In a sense, by treating Somalis with suspicion, the Ethiopian state has alienated them from the national narrative. Consequently, many Somalis in Ethiopia have preserved a sense of separate identity, often looking to Somalia proper as both a cultural and political homeland.

For Somalis in Ethiopia, marginalisation began with the expansion of the Ethiopian empire into the Ogaden region in the late 19th century. Unlike Ethiopia’s central ethnic groups, who were predominantly Orthodox Christian highlanders, Somalis in Ethiopia were Muslim pastoralists with a distinct linguistic and cultural heritage. When Emperor Menelik II annexed the Ogaden, the Reserved Areas, and the Haud, Somalis were forcibly integrated into an Abyssinian state that did not recognise or value their customs or way of life.

In my recent book, Cries in the Hinterland, published in 2022, I describe how the imperial government imposed harsh policies that disregarded the nomadic lifestyle of Somalis, restricted their freedom to practise Islam, and minimised their political representation, fostering a sense of exclusion that carried across generations. This marginalisation intensified under Emperor Haile Selassie, whose centralised approach to governance prioritised an Ethiopian identity centred around Orthodox Christianity and Amharic culture.

From the outset, the Somali in Ethiopia was never truly considered Ethiopian.

Charles Geshekter, an American historian specialising in 20th-century Somalia, described how, despite the unifying factors that distinguish the Somali way of life from “the life and ethos” of Ethiopian highlanders, Ethiopia laid claim to Somali lands yet treated the Somali region as a buffer zone, intended to protect it from perceived threats posed by other Somalis.

This position was articulated by Emperor Haile Selassie in a 1950s letter to Belata Ayele Gebre, then governor of the Hararghe Awraja in eastern Ethiopia. In his letter, Haile Selassie argued, “no house will be safe without a fence, and the fence of Ethiopia will be the Somali and the desert.”

The dispute over Somali identity in Ethiopia was highlighted in a 1948 letter that elders from the region sent to a United Nations Four Powers delegation meeting in Mogadishu, Somalia. In their letter, the elders argued that grouping Somalis with Ethiopia was “artificial and impractical,” as their connection with the Imperial Ethiopian Government was “purely nominal” and could not be justified on any grounds.

This attitude has often led to Somali-led insurgencies for self-rule and autonomy, further deepening Ethiopian suspicions toward the Somalis. This culminated in 1977 when Somali rebels in Ethiopia, supported by regular units of the Somali National Army, engaged in the largest battle of its kind against Ethiopian forces over control of the Ogaden region.

Conversely, the brutal counterinsurgency campaigns pursued by successive Ethiopian governments left long-lasting scars, further reinforcing Somali perception that they were a distinct, marginalised group within Ethiopia, bound to a separate Somali identity.

Following the fall of Mengistu Hailemariam’s regime in the early 1990s, Ethiopia finally appeared to recognise the diverse identities within its borders by introducing ethnic federalism as a governance framework. The right to self-rule was enshrined in Article 39 of a newly adopted constitution. The political landscape seemed to shift dramatically, with the new constitution guaranteeing—at least on paper—a degree of autonomy for Ethiopia’s ethnic groups over their internal affairs.

The ethnic federalism policy led to the establishment of today’s Somali Regional State, with assurances of local governance and control over regional matters such as language, education, and cultural practices. Somali language was introduced in schools, and cultural festivals celebrating Somali heritage received official recognition. Dhaanto, a Somali folk dance, became immensely popular within Somali communities.

However, the promise of ethnic federalism turned out to be less about Somali self-governance and more an updated mechanism for Ethiopian state control. Federal officials appointed Somali leaders who prioritised the interests of Addis Ababa over those of their own people and were often more loyal to the government than to their communities. For instance, those appointed to regional presidencies or federal positions are immediately dismissed if they deviate from the central party line. In essence, federal officials maintain a strong central grip over regional affairs, meaning the government has updated its toolkit for the suppression of Somalis. People from the community were anointed to do the government’s bidding.

However, the promise of ethnic federalism turned out to be less about Somali self-governance and more an updated mechanism for Ethiopian state control.

Take the infamous Abdi Iley, a former president of the Somali region, as an example. Many viewed his leadership as a tragedy—a local leader empowered by the state to rule with an iron fist, using the notorious Liyu Police, a paramilitary force, to keep people in line.

To many, Abdi epitomised the dark side of ethnic federalism: local autonomy on paper but not in practice. In essence, there was what Tobias Hagmann, a scholar of the Somali region, described as a “patron–client” relationship between Abdi’s administration and the military/security apparatus of the Ethiopian government. One Ethiopian political analyst drew a comparison between the relationship Vladimir Putin had developed with Ramzan Kadyrov of Chechnya—who, while serving as an enforcer for the Kremlin, enjoyed cultural autonomy under a regime subservient to Moscow—and Abdi's relationship with Addis Ababa’s elites. “He’s a son of a bitch,” the analyst quipped, “but he’s our son of a bitch.”

Despite Abdi Iley’s efforts to fully Ethiopianise the Somali identity, Somalis in Ethiopia eventually became disillusioned with how ethnic federalism played out on the ground. To many, it was evident that autonomy was a façade—a means for the Ethiopian government to contain regional aspirations rather than empower them. This has never been truer than it is today.

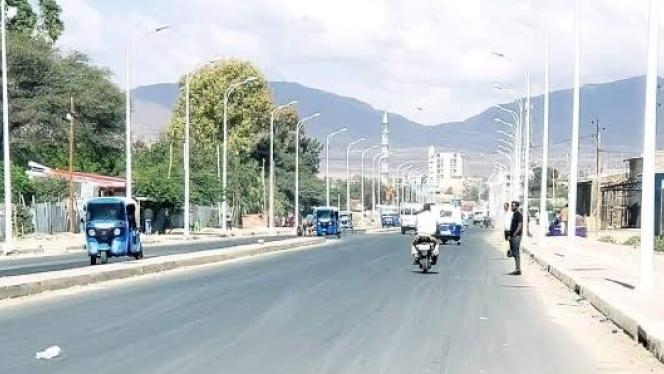

A fragile peace and a calm wind

Today, the Somali region is the most stable and peaceful in all of Ethiopia. In Tigray and Oromia, conflicts rage, and the Amhara region is ablaze, with Fano fighters facing government forces daily. By contrast, the Somali region remains the calmest, with increasing representation in national politics; Ahmed Shide, for example, is currently finance minister, a post he has held for more than half a decade, and Adem Farah, another Somali, holds the post of deputy prime minister. Shide and Farah are arguably the most powerful Somali politicians in Ethiopian history.

Abiy Ahmed has altered the Ethiopian state’s approach to ruling its peripheral Somali region. Whereas the previous strategy under the EPRDF relied on appointing Somalis to control their territory as agents of Addis Ababa, Abiy has now shifted to co-opting and enticing their most capable politicians to join his team in the capital. This is of course different from the days when members of Ethiopia’s core ethnic groups loyal to the state were deputised to oversee and brutalise Somalis. However, while the surface may seem serene today, there is an undercurrent of fear, as any challenge to Ethiopian authority could provoke a wave of repression.

Whereas the previous strategy under the EPRDF relied on appointing Somalis to control their territory as agents of Addis Ababa, Abiy has now shifted to co-opting and enticing their most capable politicians to join his team in the capital.

Many view the existing calmness as akin to a silent film—devoid of the real voices and concerns of the people. Publicly, there is a performance of unity with Ethiopia; privately, many voice doubts and frustrations, longing for genuine regional autonomy rather than top-down peace.

For most Somalis, the current façade of peace does not equate to real stability. Rather, it is a daily exercise in restraint—learning to express identity without crossing boundaries, celebrating Somali culture while knowing that political representation and economic development remain largely out of reach. This reflects what academics refer to as negative peace.

In his pamphlet on Ethiopian identity and nationality, Wallelign Mekonnen drew on the work of Franz Fanon to understand the condition of minoritised groups in the country. He wrote: “To be an Ethiopian, you must wear an Amhara mask.” While the nature of this mask may have changed over time – it isn’t necessarily any longer an Amhara facade – many Somalis feel they still have to wear one in order to get by.

Unresolved and resilient

For Somalis in Ethiopia, identity is not so much a fixed label as a way of being in the world—one that is characterised by pride, resilience, and the ongoing struggle to remain authentic. Their identity, therefore, is a nuanced and powerful force—a quiet protest against the confines of the Ethiopian state. In many ways, Somalis are both part of Ethiopia’s fabric and distinct from it, a people whose dreams of full self-determination remain deferred.

A now-infamous incident involving Somali students at Jigjiga University confronting Mustafa Omer, the current regional president, illustrates this point well. In a widely circulated video of the incident, the president questions the students about their national identity, asking them in Somali, “Idinku miyaydaan aheyn Itoobiyaan?”, which translates to, “Aren’t you Ethiopian?”

In a raucous voice, unified response, the students reply, “we are Somalis.” When the president follows up with, “but which country are you part of?” the students respond, “We have nothing to do with Ethiopia. We are from Ogadenia. Ethiopia is occupying our land!”

President Mustafa’s question was intended to promote a sense of Ethiopian unity, emphasising the interconnected nature of Somali and Ethiopian identities. Abiy Ahmed, the prime minister, called this medemer, or integration, a key slogan he peddled after coming to power. This is now also being echoed by senior Ethiopian officials like Redwan Hussein, who even when addressing Somalis in Somalia posted on X: “Ethiopia & Somalia are not just neighbors who share a border, but they are fraternal nations sharing a common language, culture & people.”

Mustafa Omar’s approach is also aligned with a vision of Ethiopia that embraces all ethnic groups while remaining cautious about the risks of ethnically driven political divisions. However, this perspective sparked backlash from the students and the wider Somali community, who wished to remain true to their authentic identity, illustrating the nuanced relationship described above.

The exchange also highlighted the type of Somali nationalism President Mustafa Omer appears to advocate publicly: an Ethiopian-oriented Somali identity that proudly acknowledges its heritage and cultural ties yet remains firmly integrated within the Ethiopian nation-state. This identity promotes integration and political engagement as a means of addressing regional issues, without pushing for separation or complete autonomy.

In principle, President Mustafa does not oppose the idea of full self-determination or autonomy. Yet, by framing Somali identity in a way that encourages an Ethiopian orientation, his stance, much like that of his predecessors, aligns closely with Ethiopia’s federalist goals. This position, however, is strongly rejected by most Somalis in Ethiopia, who not only seek regional rights but also the right to full self-determination, much like the students at Jigjiga University.

The shifting dynamics surrounding the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) in Ethiopia’s Somali Region similarly reflect a complex evolution of political and ideological perspectives, shaped by both regional autonomy under Ethiopia’s federal system and local governance changes since President Mustafa Omer’s administration took office.

Historically, the ONLF was a prominent armed group advocating for the full self-determination of Somalis in Ethiopia, at times even calling for outright secession. In recent years, however, the ONLF has moved towards peaceful political participation rather than insurgency, signalling a pragmatic shift in its approach. It put down its guns in 2018 after Abiy Ahmed came to power and decided to continue its struggle in a civic and non-violent manner. Yet, there is little difference between the ONLF’s newly adopted stance and President Mustafa’s vision of a Somali region that is autonomous but integrated within Ethiopia. Both positions remain at odds with the aspirations of the Somali population in Ethiopia.

Tensions have also resurfaced with the ONLF, which has announced it is reassessing its 2018 peace agreement with the Ethiopian state. A senior official from the organisation stated that, although peace has been maintained in the region, few other promises made by Addis Ababa’s elite—such as integration, resettlement of Somalis, and addressing the underlying issues of the conflict—have been fulfilled.

This situation has been exacerbated by recent provocative statements from officials close to Abiy Ahmed. Birhanu Jula, the army’s chief of staff, described the ONLF as an Egyptian-backed “enemy” of Ethiopia which has led to a fierce backlash from ONLF officials. This speaks to the way some parts of Ethiopia’s elite continue to view Somalis as a fifth column. The decision to erect a monument to the 77’ war in the Karamardha mountains near Jigjiga also reflects a tone-deafness towards Somalis at the centre.

The evolution of Somali identity in Ethiopia is, thus, a story of resilience in the face of systemic marginalisation and ongoing political constraints. While ethnic federalism initially offered hope for greater autonomy, it has, in many respects, perpetuated the historical patterns of control and exploitation. Somalis are, in essence, forced to navigate a political system that offers recognition of some aspects of culture without empowerment, representation without accountability. As Tom Gardner noted in his book, The Abiy Project, an unnamed presidential advisor told him that the region was “stable but not peaceful”. “We’re not yet at peace with ourselves,” he said, “and we’re not yet at peace with the Ethiopian state.”

This experience—an intricate balance of cultural pride and political manoeuvring—suggests Somalis are true survivors of a system that has yet to truly embrace their aspirations. However, it remains to be seen how their identity might evolve as the inhabitants of the region, to paraphrase Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, speak for themselves.