Sunday 6 October 2024

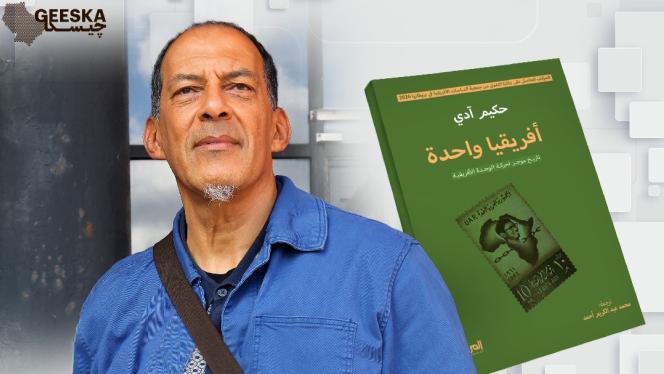

History as a tool for change; an interview with Hakim Adi

Professor Hakim Adi, the first professor of the history of African heritage in the UK, speaks to Geeska about Pan-Africanism, Africa’s relationship with China, and his belief in history as a tool for change.

Professor Hakim Adi is a prominent British-Nigerian pan-African intellectual and historian. Adi is also the first Brit of African heritage to become a professor of history in the UK. He has dedicated much of his life to uncovering the histories of Africans and African diasporas, while also reflecting on the African and Black intellectual tradition and the resources it provides us for thinking about how solidarity among African peoples might be cultivated.

But what is pan-Africanism? Adi provides us with a pithy and sharp definition. In his 2018 book, Pan-Africanism: A History, he writes: “What underlies the manifold visions and approaches of Pan-Africanism and Pan-Africanists is a belief in the unity, common history, and common purpose of the peoples of Africa and the African diaspora, and the notion that their destinies are interconnected.”

The importance of this idea permeates his work. It guides his historical inquiries as he seeks inspiring examples of instances when Africans have demonstrated this solidarity with each other. It also shapes his interpretation of these stories and the lessons he derives from them. “Studying history,” he says, “enhances people’s cultural awareness and their capacity for change.” For him, history is a tool, not merely a subject of curiosity.

Adi has been very busy of late. In August he received the Outstanding African Studies Award for 2024 from the African Studies Association of the UK. He has also been travelling; he visited Cape Verde, where he participated in the centenary celebrations of the birth of the late anti-colonial leader Amílcar Cabral. He then travelled to Cairo, the historic centre of anti-colonial activity, to launch the Arabic translation of his book Pan-Africanism: A History.

In this interview with Geeska, Adi discusses a number of his academic interests, challenges in African history, Africa’s role in the Global South and what it will take to liberate Palestine. He also shares an anecdote from an audience with Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni which said a lot about the state of African relations with the western world.

Mohamed Abdelkarim: When surveying your work, it is evident that you emphasise the role of the African diaspora in shaping the broader Pan-African movement. How significant was this role in the past, and how important is it today?

Hakim Adi: Pan-Africanism, as a concept, is fundamentally linked to two key ideas. The first is the development of African self-awareness, which became evident in the work of Olaudah Equiano (born in Nigeria in 1745, died in London in 1797). His book, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa the African, Written by Himself, sheds light on the suffering of Africans during the slave trade in the second half of the 18th century. It was a work that presented the experiences and identity of Africans, regardless of their tribe or place of origin within Africa.

The second factor is the African revolution in Haiti (1791–1804), where half a million Africans from various parts of the continent lived. By successfully establishing a clear pan-African presence, it laid the foundations for equality among all the island’s inhabitants, whether African, European, or mixed-race (affranchis). Furthermore, this revolution served as an inspiring African model in the 19th century, particularly since the Africans managed to defeat the British and French armies, boosting confidence in their ability to resist such powers.

This suggests that pan-African ideas, like a river branching into many streams, initially emerged in the diaspora and began spreading across the continent in subsequent decades. Since the establishment of the African Union, the diaspora has played a crucial role, enjoying a prominent status within the union and contributing dynamically to its institutional work.

MA: As a professor of African history, how relevant is the study of this subject today, particularly among the youth, given the rapid changes sweeping the continent technologically, socially and even with major protest movements?

HA: In my opinion, studying history is mainly about one thing: change. And this change is, at its core, a recurring individual act. Through the culmination of various experiences and contributions, individuals (Africans) can develop awareness, thereby enhancing their capacity to drive change, as we are currently doing.

Before arriving in Cairo, I attended the centenary celebrations of Amílcar Cabral in Cape Verde. There were many questions about the relevance of celebrating Cabral’s centenary, given the current rapid changes in the Sahel and Guinea-Bissau. The clear response is that Africa still needs to understand Cabral’s ideas, which I consider to be among the most important of any African thinker in the post-independence era, especially his study of the identity and leadership of the colonised in the context of national liberation, class consciousness, and Marxist theory. Cabral’s significant insight, which we emphasise today, is that culture is the primary element in achieving national liberation.

Thus, studying history enhances people’s cultural awareness and their ability to change, even within their immediate surroundings. Personally, this perspective has been present throughout my life.

Decades ago, I sought to become a history teacher at the pre-university level, but I was systematically prevented from doing so until I obtained a PhD in history and began working at the university. I became the first Black professor of African studies in Britain. About ten years ago, I launched the Young Historians Project, which currently includes 20 master’s degree researchers studying various issues related to Africa and the African diaspora.

Despite challenges such as funding and topic selection, the project has become important and has the potential to expand to other African or Caribbean countries. This is a form of change to which I claim to have contributed, after years of neglect, in advancing the study of African history from an African perspective in Britain. This has been reinforced by the subjects chosen by researchers, such as the history of Black people in 15th-century Britain, an issue that has raised awareness and is now being openly discussed with fewer sensitivities. This represents a significant change brought about by the study of history as a tool for transformation.

MA: What are some of the biggest challenges you see in the academic study of African peoples, their ideas and diasporas?

HA: The issue is extremely complex. There are problems related to the methodology of studying African history and breaking away from Eurocentric ideas. For example, most European historical writings classified Egyptian civilization as European (or perhaps Mediterranean) until a generation of African historians, led by Cheikh Anta Diop, dismantled these assumptions and provided evidence that Egyptian civilization was profoundly African. Diop’s evidence was ridiculed by Egyptologists at the time, but over time, the strength and accuracy of his arguments became clear, while the ideas of European Egyptologists faltered.

One of the issues in the field of history is that this historical debate, once led by a giant like Diop, has passed to non-historians like Molefi Asante, whom I do not consider a historian. His ideas, like Afrocentrism, while widely debated, do not merit serious scholarly engagement, reflecting the state of African history studies in the US. In Africa, during my recent visits to Nigeria and other African countries, I observed a decline in the study of history. I’m not optimistic about a general review of the field, as there are significant challenges, such as funding cuts and the lack of a clear vision.

MA: Speaking of Afrocentrism, what is your view on the idea and it’s debates?

HA: Afrocentrism appeared frequently in pan-African thought, predating both Diop and Asante. I believe Afrocentrism can be seen as an expression of a deep African desire to associate Egyptian civilisation with Africa, to which it undeniably belongs, given the evidence in Nubia and various regions of the Sahara.

Is that African desire to connect with Egyptian civilisation, or vice versa, a cause for concern for Egyptians (for example)? The issue is, of course, subject to debate, as seen in the portrayal of Queen Cleopatra as a Black African. There are different views on Cleopatra—was she European, Macedonian, Egyptian, or African? What was important in this debate was discussing the African identity of Egypt and questioning the effectiveness of viewing identity as something rigid, static, and immune to social or historical changes.

Conversely, we can debate the Arab and Islamic influence on Africanity, which remained limited until the early 20th century. Contributions from figures like Muhammad Ali Doss (whose identity—Egyptian or Sudanese—remains debated) and individuals from North Africa during the periods of liberation from French colonialism reflect the inclusivity of Pan-Africanism. It encompasses various branches, all aiming to find collective solutions to the problems facing Africa and its people. Pan-Africanism does not exclude ideas that promote unity, and Afrocentrism, possibly one of its tributaries, holds some validity.

MA: A notion is being promoted about the reformation of the Global South. What role does Africa have in this process?

HA: Africa currently faces challenges at multiple levels. Its governments and political systems are legacies of colonialism, and they do not clearly represent African interests. Deep-rooted issues remain for Africa to address. According to the prevailing view, China is leading this process; yet China is no different from traditional colonial powers when it comes to resource exploitation and alliances with ruling elites who do not represent their people.

This Chinese scramble for Africa, like any colonial scramble, poses a serious threat to changing the course of African history.

The liberation from apartheid in South Africa was achieved through national struggle, supported by African efforts in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and even North Africa. In Palestine, we find that Zionism is supported by countries like the United States and others. Similarly, the liberation of Palestine will require external support, much like the case of South Africa. Thus, Africa’s role in the Global South (or in the international community) cannot succeed without the unity of African people, rather than relying on governments that, I believe, are not serious about the idea of the Global South, as they are themselves products of colonialism.

China will not provide loans and aid to African countries without expecting something in return, even if the interest rates are lower than those imposed by the IMF or western countries. The idea of accepting China’s offer of “developmental participation” is merely replacing one monster with another. I recall attending a meeting about 20 years ago under the African Union’s sponsorship.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni addressed us, a group of African intellectuals, expressing that he felt like a “schoolboy in front of the headmaster” when meeting the US president. This is not the kind of speech Museveni would give to his people or in other official meetings. I believe this reflects the level of most African leaders, and thus, little can be expected from them. Even the African Union remains just neo-liberal platform and has done little to help the people of Africa in crises like those in Congo, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Somalia, or earlier in Libya. The union, which Muammar Gaddafi invested in founding, was unable to take any stance regarding Nato’s intervention.

MA: In what sense can we think of Africa as post-colonial then? To talk of neocolonialism is even a push.

HA: Certainly, Africa today has inherited the borders between its countries, inherited Western political systems, and inherited elites clearly aligned with the coloniser. Hence, I believe that Africa has not yet reached the threshold of a “post-colonial state”.

MA: What is in store for readers from you moving forward?

HA: I have a book in progress, one that I think is important regarding the history of Africa, but from the perspective of stimulating a cultural-intellectual debate about this history. I have initially divided it, and its outlines are gradually becoming clear. However, the first chapters have been finalised, which will address the history of Egypt and its African issues, then Sudan or Nubia and the surrounding areas. I look forward to a comprehensive exploration of the contentious issues related to the history of the African continent in various regions, but the work is still open to development and may take around two years or so.