Thursday 21 November 2024

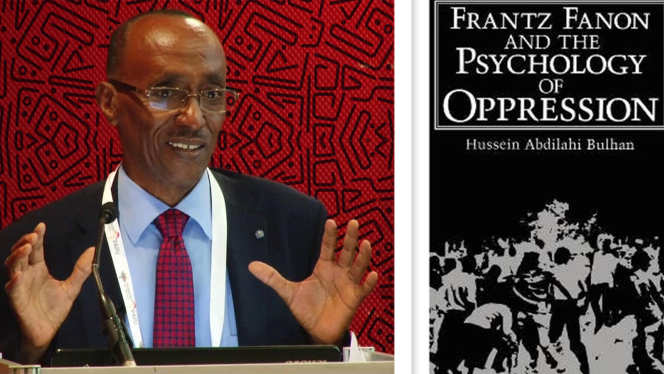

Hussein Abdilahi Bulhan, Fanon and Gaza

As Israel’s genocide in Gaza continues, Hussein Abdilahi Bulhan’s work on Fanon acts as an urgent reminder of the role of psychology in resisting oppressive systems not accommodating us to them

As an anti-racist psychologist, Professor Hussein Abdilahi Bulhan has long remained a treasure. His work has been inspirational, and the echoes and traces of his ideas permeate my writing, teaching, and practice. Yet to my dismay, Bulhan is not often discussed among anti-racist scholars and critical mental health professionals in the Global North. This must change, not least in our current zeitgeist. Liberal acceptability of settler-colonialism has re-emerged within our profession. The complicity of mental health professions in imperialism is unfortunately on full display. Now, more than ever, the work of the professor and founder of the Frantz Fanon University in Hargeisa deserves to be elevated.

A good book is immediately impactful. But a great book stands the test of time, demanding that we re-read and re-engage with its ideas as we comb out fresh meanings from the text. Bulhan’s “Frantz Fanon and the Psychology of Oppression” is precisely such a book. It resonates today because the toolkits available for oppressive systems and the conditions which facilitate their operations have evolved significantly (i.e. state surveillance, artificial intelligence & an atomised society). In the book, Bulhan expertly weaves a biography of Frantz Fanon (with first-hand sources from the Fanon family) as he explores the historical complicity of western psychology in scaffolding oppressive systems. It’s this combination of skillful biography and a deep appreciation of Fanon’s work, while maintaining his own position of analysis, that allows Bulhan to sketch out what a truly liberated field of psychology could look like.

Bulhan begins by giving us an uncompromising glimpse into Fanon’s life. We learn, for example, of Fanon’s intransigence against injustice—an honourable quality that, for people of colour, remains hyper-managed to this day. It was precisely this impulse that led him to fight the Nazis alongside the French; then later against the French alongside the Algerians. Some scholars today attempt to sanitise Frantz Fanon and give him a sheen of liberal acceptability or to co-opt his story and legacy to enhance their own brands. Worse, some even claim he would accept the Zionist settler-colonial project. But a deep reading of his life, via Bulhan and confirmed by Josie Fanon (Frantz’s late wife), reveals the absurdity of this. He was utterly uncompromising when it came to oppression.

Through Bulhan, we learn that Fanon confided a regret to his mother: fighting for a people (the French) that humiliated him. These details are essential to understanding Frantz Fanon’s development, providing emotional insight into the experiences of racialized minorities in the Global North who still engage with its institutions.

In Bulhan’s account, we discover the character of Frantz Fanon’s relationship with his mother, who concluded all her letters to her children with “Your mother who prays for you.” However, with Frantz, she signed off with; “Your mother who marches with you.” Frantz Fanon was far from being rejected by his mother, which was a popular theory at the time attempting to psychologise his defiance. This is akin to the theories we hear about Muslim youth dedicated to combating oppressive systems abroad. The strong will of revolutionaries is often nurtured in subtle ways, primarily by mothers. The will to resist oppression is not a psychological aberration, but the unfolding of a conscious political project.

Bulhan then introduces modern psychology by affirming what most psychologists overlook: the dominance of the Global North in the world. Bulhan’s critique of Eurocentric psychology weaves his analysis with Fanon’s, merging the two together. As Bulhan observes: “Indeed, the greed that consumed other peoples and hoarded earthly resources may soon cannibalize itself before conquering outer space. Yet, what have psychologists said and done about this historical rampage and potential self-annihilation?”

Bulhan’s answer builds naturally on Fanon—it is not a summary but an expansion. He provides tremendous analytical insight, progressing toward his liberation framework within psychology. Bulhan outlines three significant changes needed for psychologists to free themselves from the asphyxiating cloak of domination: a renewed emphasis on collective well-being, our needs, and empowerment. I will briefly outline how these ideas impacted my work and why they matter for Gaza.

First, Bulhan asserts that we must shift the emphasis from individualism toward collective well-being. This assertion may sound obvious; collective well-being is a principle that socially conscious psychologists claim to adhere to. However, psychology today remains beholden to a range of stakeholders and a neoliberal zeitgeist which has hijacked policymaking and necessarily individualises distress. Consequently, public mental health services still strongly prioritize an individual’s mental health based on their ability to work and remain productive citizens, not healthy humans.

Those psychologists who avoid public mental health services are often compelled to work within the highly individualised, middle-class enterprise of private therapy. This situation is even worse for people of colour. The ideal of collective well-being is obstructed for racialised minority communities like Muslims; the processes of their marginalisation operate within the domain of liberal acceptability—such as counterterrorism. Therefore, while innocent Muslims are far more likely to be stopped at airports under counter-terrorism legislation, this is perceived as necessary for much of the public. Providing individual therapy for each false positive arrest would merely gloss over the collective violence that affects all Muslims. It is a systemic and structural problem and not a personal one. This is particularly true for the people of Gaza, who are collectively dehumanised by Zionist apartheid. Their collective well-being requires liberation from Zionism, not a hyper-individualised “trauma therapy,” as Dr. Samah Jabr argues.

Secondly, we must shift away from an emphasis on instinct—derived from psychoanalysis but can also be understood as any focus on an individual’s psychological makeup—to a focus on needs. Here, Bulhan particularly emphasises the need for self-determination. The emphasis on needs rather than instinct is crucial. The key element is the process of psychologisation.

Bulhan, drawing on Fanon, reminds me to consider the actual conditions of the person before me. This is especially relevant for Muslims who have been abused and disenfranchised by the state and its various institutions. Psychology has had a long, committed relationship with people authorities deem to be ‘anti-citizens.’ But at the heart of their struggles, I always remark on unmet needs which flourish under second-tier citizenship. The need for justice. The need for accountability. Most of all, the need for self-determination; to decide one’s future outside of state management and surveillance. To psychologise these needs—to concentrate solely on anger, anxiety, and depression—mises the woods for the trees. Bulhan’s text is a strong reminder to resist the impulse to psychologise structural issues within individuals.

Third, and crucially, Bulhan argues we must shift our focus from adjustment to empowerment. Long has therapy been a political enterprise in supporting individuals to acquiesce and adjust broadly to the structures that marginalise them. Bulhan’s alternative, empowerment, is not a rehash of neoliberal “resilience” where individuals are “empowered” to overcome life’s adversities. Rather, it is a demand to go beyond therapeutic. As Bulhan summarises poignantly, “psychological work with the oppressed must give priority to organised and collective activity to regain power and liberty” (p. 276). Organised, conscious and collective action must precede the therapeutic. This most crucial dimension I’ve taken from Bulhan’s work, which now reverberates across all of mine, is his emphasis on empowerment rather than adjustment. He summarises the need for it in a series of questions every psychologist should be asking themselves:

“Now assuming that a member of the oppressed seeks psychotherapy and it is provided, that appointments are kept, and that therapy proceeds as planned, what realistic changes can be expected? Is it not a worthy accomplishment if at least the anguish of symptoms and a self-defeating pattern of behaviour have been changed through psychotherapy? At the same time, however, was a concession made to the prevailing social order by affecting adjustment to it? Is it reasonable to state that psychotherapy may be appropriate and necessary for this patient, but essentially conservative with respect to the status quo of oppression? Is psychotherapy therefore basically an instrument of social control, not social change? If so, are there ways of helping this victim with his immediate, specific, and pressing problems but not by compromising the goals of the collective?”

As an anti-racist psychologist who works primarily with clients impacted by state violence, security, and border policing, these are questions I pose myself often. When I see clients who’ve been abused by police, for example, is it adequate for me to support them with their “trauma” or is there something I’m missing by bandaging the dire consequences of violent social control which harm racialised communities?

Empowerment would entail empowering the client to develop or find the structures they need to feel protected. And if these structures do not exist? Then this is the praxis of Fanon’s sociogenic approach: every story uniquely reveals the limitations of our collective power and liberty. Therefore, their stories become especially meaningful, not just for themselves, but as guides to diagnose and resist structures of oppression. This step of empowerment is more significant than therapy itself. Indeed, without it, therapy is nothing but a tool which dismisses the sociogenic significance of their distress.

And this is especially true for Palestine. I recently claimed on social media that psychologists eyeing the genocide in Gaza with an impulse to give “therapy” are part of the problem. To this, an American social psychologist responded that some people are doing what they can, and I was being too harsh. But this is exactly the issue Bulhan is urging us to consider: is the clarion call for Palestinian liberation really a question of therapy? Or does our emphasis on therapy conveniently overshadow the need to collectively mobilise and resist structures of imperialism, Zionism included?

If we are serious about oppression, we have no other choice but to follow in Fanon and Bulhan’s footsteps and realise that the struggle for justice and liberation precedes therapy. These have been short reflections on Bulhan’s work, but in time I could write a book to draw out its many inspirations. His seminal book is a biography, a critique of contemporary psychology, and a prime example of unearthing the ever-presence of politics in mental health.