Sunday 8 September 2024

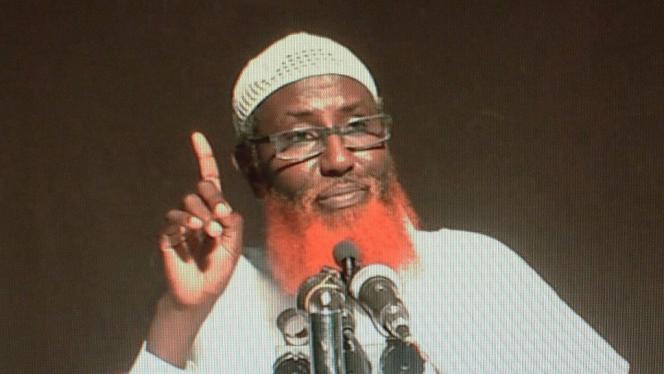

Abdulqadir Mumin as IS caliph would challenge its dogma, says Christopher Anzalone

After reports named Abdulqadir Mumin as global leader of ISIS, Geeska interviewed expert Christopher Anzalone to discuss IS-Somalia’s growing influence in the IS network and examine the reports’ credibility.

On 31 May, Africom (US Africa Command) issued a relatively routine statement regarding an airstrike it conducted on IS militants in Dhaardaar, a town located just under 100 km from Bosaso in Puntland. The statement adhered to all the conventions of Africom messaging: it was conducted in collaboration with the federal government, reported no civilian casualties (as usual), and confirmed the elimination of three militants.

Just two weeks later a journalist at NBC News followed up, putting out a report with extraordinary implications if true. Citing two unnamed US officials, Courtney Kube reported that the US targeted IS-Somalia’s leader, Abdulqadir Mumin, in the strike, who was likely also the global head of IS, according to those officials. That would suggest that IS’s core leadership in Iraq/Syria, who have taken a keener interest in Africa of late, have voted with their feet and moved their franchise to the continent where they’re most active. That raised a few eyebrows among experts familiar with the group as it seemed unlikely and quite surprising.

So, we’ve arranged an interview with Christopher Anzalone, a leading expert on jihadist groups globally, and especially those operating in Somalia. He is a research assistant professor with Middle East Studies and the Krulak Center at Marine Corps University. Here is our Q/A with him on the origins of IS, the likelihood that it has selected Abdulqadir Mumin to be group leader and the nature of their operations in Somalia and Africa more broadly. The views expressed here are his own.

Faisal Ali: Let’s start at the top. Could you tell our readers a bit about IS’s Somalia branch? Most people don't know much about its presence there or consider it a lesser concern due to the much more powerful al-Qaida affiliate, al-Shabaab (AS), in the south. How did it emerge in Somalia, and how powerful is the organisation there compared to its other IS peers globally?

Christopher Anzalone: Islamic State-Somalia (IS-Somalia) emerged in 2015 when Abdulqadir Mumin, who was then a prominent preacher in al-Shabaab from Puntland, publicly defected and pledged allegiance to Islamic State “core” leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Mumin took full advantage of his familial and sub-clan/clan ties in Puntland to recruit. IS-Somalia was also able to attract some AS fighters and mid-level commanders to defect, though these defectors were mostly hunted down and either imprisoned or killed outright by AS. Though it still has some cells in southern Somalia where it continues to extort money from merchants and businesspeople, the IS-Somalia stronghold is, and has always been, in Puntland, particularly in and around the Golis Mountains.

FA: Why did it splinter from al-Shabaab? Was it more of an ideological difference with AS’s leaders, or a case of personality clashes that couldn’t be resolved, combined with the opportunity to fill a vacancy for a new local IS franchise?

CA: The reasons for Mumin’s decision to defect aren’t fully clear. Although he played a fairly prominent public role in AS public “diplomacy” – for example, he was one of the AS officials tasked with negotiating with local clan elders in and around Mogadishu in 2011-2012 when AS was facing serious battlefield setbacks – he may have felt that by defecting he’d have, so to speak, better career advancement prospects. His defection also came at a time when IS core’s global image was on the rise following the fall of Mosul and rapid IS sweeps across parts of Iraq and Syria, lending an aura of inevitability to IS in its then increasingly violent feud with al-Qaida core and its regional affiliates and allies. Though Mumin gave ideological reasons – and not to discount them – it is very likely that his personal ambitions and, possibly, internal power struggles in AS’s Puntland forces also played a role in his decision to defect.

He may have also calculated that he had a good chance of avoiding serious consequences from AS because the group is substantially weaker in terms of its capabilities in Puntland compared to much of southern and parts of central Somalia. Mumin was also fortunate that a March 2016 attempt by AS to land forces by sea – 600 fighters, according to Somali regional government officials, vastly outnumbering IS-Somalia’s estimated 150-200 fighters – was foiled by poor insurgent planning and interventions by the Puntland and Galmudug regional state administrations’ security forces.

FA: A recent report by the International Crisis Group on IS operations in West Africa gave a detailed account of the financial and logistical support IS provided to its branches in northern Nigeria and the Lake Chad region. Much of that support was also know-how, from video editing to teaching their counterparts about different weapons. Do we know much about the type of relationship IS-Somalia has with the core leadership?

CA: In terms of minute details, much about the relationship between IS-Somalia and IS-core remains unknown. However, IS-core has previously outlined how its internal administrative and organisational structure works – at least in theory – to connect the core organisation with its regional affiliates, including those across Africa. IS-Somalia made dramatic improvements in its media operations between 2015 and 2017. The earliest IS-Somalia videos were either released without official IS branding or through a subsidiary IS media branch often used to publish videos dealing with issues and events outside the Levant and Iraq. Within a couple of years, IS-Somalia and its media had been fully incorporated into the official IS-core media organisation, with production quality and narrative styles matching identically the media output of other Islamic State affiliate branches inside and outside Africa. In terms of military capabilities, there does not seem to have been as much of a noticeable change, which is unsurprising considering the initial core group that made up IS-Somalia came from al-Shabaab and likely didn’t lack weapons know-how.

FA: On 15 June, NBC reported that the US targeted Abdulqadir Mumin, IS-Somalia's leader. However, two anonymous US officials in the NBC report claimed that he is also the organisation’s global leader, succeeding Abu al-Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi. There is some scepticism around this, not least because Somalia isn’t really the focal point of the organisation’s activities. One expert even suggested the organisation simply isn’t ready for a black leader. What are your thoughts on the likelihood that Mumin is now its leader?

CA: It seems clear that IS-Somalia, helmed by Mumin (if he wasn’t killed recently), has become an increasingly important affiliate branch in terms of financial administration and coordination via the al-Karrar Office. It’s within the realm of possibility that this also includes a more prominent role for him in the broader Islamic State network. Elevating him to the position of amir of the core organisation, however, would pose significant challenges to IS. Chief among these is the fact that Mumin is not, and has not claimed to be, a direct male descendant of the Prophet Muhammad (a “sayyid”). Being of Quraysh descent, has, up to this point, been a requirement (at least in the form of claimed lineage) for each of the Islamic State’s so-called “caliphs” and, more generally, a widely accepted historical requirement in Sunni conceptions of who can be a caliph. This in itself isn’t racist, but it is exclusionary regarding who can and who cannot be a “caliph.”

Mumin’s non-sayyid status would contradict a significant body of Islamic State discourse and propaganda materials, including political and theological publications and messaging. Despite Islamic State’s rhetoric of brotherhood and the absence of any kind of divisions or differentiation between Muslims, who should be united first and foremost by their common religious beliefs, the reality is often different.

There were other reports that senior Islamic State core leaders, including the current amir/“caliph” Abu Hafs al-Hashemi al-Qurashi, may have relocated to Puntland because of its freer operational environment. Some questions that emerge from these reports concern the extent to which Puntland offers an easier operational environment than Syria and Iraq. On the one hand, there has been and continues to be a lot of pressure on the organisation in the latter two countries, and the previous three “caliphs” were killed in Syria. The mountainous and hilly parts of Puntland may be geographically attractive, and the region may also be appealing to Islamic State senior leaders as a place from which to be in closer proximity to affiliate branches that are currently the most globally prominent, those being in the Sahel, Nigeria, Mozambique, and the DRC, together with Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-KP). IS-Somalia’s reported recruitment surge, particularly targeting Ethiopians, may also make Puntland an attractive new base.

Puntland, however, also faces its own challenges, including the relatively small numbers of IS-Somalia. Despite its stronger position in northeast Somalia, it remains firmly in second place behind al-Shabaab. The proximity of Puntland to the Red Sea and Bab al-Mandab, coupled with increased U.S. military presence aimed at countering the Houthis in Yemen, may also draw unwanted attention to IS-Somalia and any Islamic State Core leaders who may have relocated there. Many non-Somali al-Qaida figures have previously found Somalia a challenging environment to operate in without clan ties, something that Mumin and IS-Somalia may offer to senior Islamic State leaders from Syria and Iraq.

FA: IS-Somalia is relatively small in terms of manpower, with estimates suggesting it has as few as 200 fighters. However, it reportedly plays a crucial role in funneling cash to other regional IS affiliates. What is known about the mechanics of this aspect of its operations, and how significant is its role as a bridge between IS leaders and its branches in Africa?

CA: There is limited open-source information detailing the specific connections and processes between Islamic State core in Syria/Iraq and IS-Somalia. In 2023, the US Department of the Treasury (DoT) released some details on how IS-Somalia generates revenue: primarily through extortion of businesses, including mobile money transfer services, banks, and other financial institutions, as well as “taxing” livestock, agricultural products, and merchants, mostly in Bosaso but also in Mogadishu. IS-Somalia then launders its funds, estimated to be in the millions of dollars, before transferring some to other Islamic State affiliates across Africa. Earlier this year, the DoT reported that Islamic State has used South African banks and cells based in South Africa to transfer funds to IS-Central Africa in the DRC, while IS-Somalia and IS-Mozambique have utilised money transfer businesses. African IS affiliates also generate revenue through extortion of farmers, and pastoralists, taxing illegal gold mines and operating artisanal mines in the DRC. Additionally, they impose “zakat” taxation on Nigerian Muslims residing within IS-West Africa’s sphere in northeastern Nigeria.

FA: The growing concern about IS-Somalia coincides with ISIS expanding its operations across Africa, perceiving it as a more hospitable environment to establish roots and operate. Despite varying contexts and differing levels of success, they’ve succeeded in inserting themselves in often quite localised conflicts. What gives them this appeal?

CA: Both Islamic State and al-Qaida’s African affiliates exhibit a hybrid approach in their organisational ideologies and operational decision-making. They tend to achieve greater success when they incorporate their transnational ideas and rhetoric into local or regional grievances. For instance, al-Shabaab positions itself as a viable alternative – albeit not always popular – to an underperforming or absent Somali federal government. Simultaneously, their use of transnationalism has historically given them an advantage over domestic competitors with similar religious ideologies, such as the Hizbul Islam coalition, whose constituent groups were more closely tied to specific sub-clans and clans.

To succeed, these groups do not necessarily need to win over all civilians; they simply need to convince enough to tolerate their continued presence or rule, rather than rebel against them. The most successful groups also persuade locals that they can maintain some semblance of law and order, provide mediation or conflict resolution mechanisms, and offer limited services and aid. In the long term, the most successful groups also take local sentiments into account to some extent, engaging with segments of the civilian community. This does not imply that local civilians have a decisive or major say, but their influence can be significant for groups that have maintained prolonged success, like al-Shabaab.