Friday 20 September 2024

Kenya’s American affair

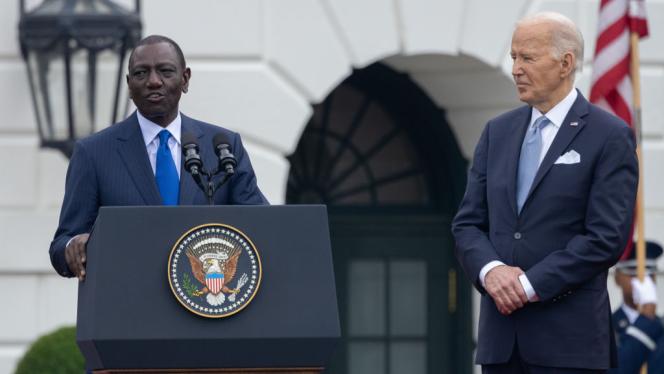

Ruto’s recent trip to the US sent a strong signal that it wants to more closely align its foreign policy with Washington’s but that won’t come cost-free

President William Ruto’s recent state visit to the White House marks a significant milestone in US-Kenya relations. Since taking office, Ruto has swiftly positioned Kenya as an indispensable American partner, earning the prestigious red-carpet treatment during his Washington trip. This visit underscores Kenya’s growing strategic relevance amid a rapidly shifting African and global landscape. In 2018, the United States and Kenya officially upgraded their relationship to a e. In 2018, the United States and Kenya officially upgraded their relationship to a “strategic partnership”. This partnership was based on five main areas: promoting economic growth, trade, and investment; working together on defence issues; promoting democracy, good governance, and civilian safety; addressing multilateral and regional issues; and collaborating on public health matters. The recent visit illustrates Washington’s view that Kenya has made significant progress in these areas, as it has secured several multi-billion-shilling transactions covering a wide range of industries. Undoubtedly, the power of these accords will extend beyond the nation’s boundaries, increasing its influence.

The counter-terrorism nexus and regional stability

The 1998 bomb attack on the US embassy in Nairobi severely strained relations between Kenya and the United States for some time after the incident. In the immediate aftermath, the US investigated the role of al-Qaida cells operating in Kenya and pushed Kenya’s government to crack down on militant groups. Since that time, Kenya has been a crucial US counterterrorism partner in East Africa, on the front lines against the al-Shabaab threat.

As Ethiopia’s role as an anchor state fades due to US concerns of severe human rights atrocities and ethnic cleansing during its recent two-year civil war, Kenya is positioning itself as a possible replacement for Ethiopia, which has been bedevilled by multiple conflicts between violent non-state actors and the central government. The region more broadly struggles with similar issues, as Sudan is caught in the grips of a year-long civil war and Somalia continues its fight with al-Shabaab.

In this context, Nairobi has emerged as a more constructive actor. Kenya is now spearheading peace discussions between the government and rebel factions in South Sudan, announcing a breakthrough in mid-May. Additionally, Kenya is actively engaged in talks aimed at diffusing tensions between Somalia and Ethiopia. An Ethiopian statement affirming Addis Ababa’s commitment to its neighbours' territorial integrity, without naming Somalia specifically, was seen as an attempt to ameliorate Somali concerns.

Furthermore, Kenya is serving as a guarantor of the delicate agreement that brought an end to Ethiopia’s violent civil war. This regional fragile security challenge necessitates close US-Kenyan collaboration.

In 2011, Kenyan troops entered Somalia to establish a buffer zone against al-Shabaab, a turning point in Nairobi’s approach to Somalia’s civil war backed by US intelligence and airstrikes. While the operation inflicted heavy losses and led to major attacks within Kenya, it disrupted the group’s bases and expelled them from urban areas. The US considers al-Shabaab “the greatest danger” to its interests in the Horn of Africa region, an assessment no doubt shared by Kenya. Concurrently, the US has relied on Kenyan facilities for drone strikes and special forces operations deep in Somali territory against al-Shabaab, providing over $1 billion in counterterrorism aid. Fighting al-Shabaab has given the Kenyan military invaluable operational experience; combined with significant US aid, Kenya’s military is one of the region’s most capable and integrated with US goals in managing the threat posed by al-Shabaab. With reports that the Djibouti government refused to allow the US and its allied forces to conduct attacks against Yemen’s Houthis from Camp Lemonnier, the US government has secured the go-ahead to expand Manda Bay to build a 10,000-foot runway.

Is Ruto's doctrine compromised or is he a master of doublespeak?

On any given day, when you watch President Ruto speak, he demonstrates an uncanny ability to lull his audiences, presenting himself as a man of strong and unwavering conviction. However, despite his oratory skills, he often performs U-turns on positions he once presented as cornerstones of his political project. He once condemned the tendency of African leaders to gather at summits organised by single states in foreign capitals, then attended the Italy-Africa summit. He frequently stirs up African sentiments and turns them into anti-Western feelings but maintains cordial ties with Western states without addressing structural issues. Despite quoting Kwame Nkrumah on CNN, saying his country favours neither China nor the US, he has strengthened his relationship with Washington. He has championed the need to take action on climate change but has also said countries shouldn’t roll back the use of fossil fuels.

Despite presenting Kenya as a constructive and stabilising actor in Africa, during last week’s Africa CEO Forum in Kigali, Rwanda, President Ruto, in an interview, contradicted UN reports on the conflict in the DRC, blaming Kinshasa for the violence in its eastern regions despite widespread reports of Rwandan involvement. Ruto’s domestic reputation has also been severely affected by high inflation, a series of unpopular new taxes, and excessive government spending. His recent trip to the US was overshadowed in his native country by discussions about the cost of the trip and his choice of a private jet to get to the US. He is a “master of inscrutability,” the Economist writes, good at making “friends abroad and enemies at home.”

Under President Ruto’s leadership, Kenya appears poised to extend this robust foreign policy posture across various political and security arenas. Ruto has firmly backed deploying a regional military force to Haiti. Kenya is expected to provide the core of a 1,000-strong UN-authorised peacekeeping contingent to help restore order amid Haiti’s spiralling gang violence and institutional collapse, a high-risk move aligning with US aims to prevent a failed state on its own doorstep.

Despite this, the government’s action has been met with significant public disapproval in Kenya. On 17 May, Ekuru Aukot, the head of Kenya’s Third Way Alliance political party and a former Kenyan presidential candidate who opposes Ruto, filed a legal challenge in Kenya’s High Court against the planned deployment of the officers. Aukot said that this action showed disrespect for the court and included other improper actions. Aukot contends that the government’s deployment violates a court ruling issued in January 2024, which deemed the police deployment to Haiti both unconstitutional and unlawful.

President Ruto has been accused of speaking left and right. During the Pan-African Parliament summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, in July 2023, President Ruto gave a fervent speech about Africa's shared destiny and the need to free itself from Western dominance. However, barely a month later, he publicly supported the reinstatement of a president who was backed by western powers in Niger. At the same time, he expressed his disapproval of how European leaders mistreated African leaders, emphasising the need for their proper acknowledgment on the global stage. He recently participated in the UN general assembly and established a strong bond with Zelenskiy, who had previously dismissed an African peace mission as insignificant. William Ruto is supporting Ukraine in its confrontation with Russia, arguing for a system of international relations based on established principles. Nevertheless, he is not demonstrating equivalent backing for Niger, an African nation, in its resistance against French hegemony.

A strategic hedge against great power rivals

When it comes to establishing strategic partnerships with significant African states, especially those in the Horn of Africa, which is the continent’s flashpoint for geopolitical activities, the United States has fallen behind Russia, China, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Turkey. As if that weren't bad enough, the United States has been losing dear friends. Ethiopia is the most recent. Despite internal unrest, Ethiopia has joined the China-led BRICS bloc, which aims to put an end to western dominance in the global financial system and create a new multipolar order.

Perhaps most crucially driving the US-Kenya rapprochement is Washington’s growing rivalry with other major powers vying for influence in Africa. As Russia’s Wagner mercenaries consolidate control across swaths of the Sahel, and China cements itself as the preeminent economic and infrastructural partner for most African states, the US faces encroaching competitors in formerly undisputed spheres of influence. To counter this influence in Horn, the US government is expanding the Manda Bay, a strategic coastal point to enhance regional security in the Somali peninsula.

Since the start of the civil war in Sudan, Russia has been courting both sides, the Sudanese army and Rapid Support Forces militia. In April 2024, the Russian ambassador openly showed support for the army. Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov also visited Sudan in late April. Moreover, Turkey’s deepening security cooperation with countries like Somalia and Libya adds another influential player to a crowded geopolitical arena.

Nairobi appears enthusiastic about leveraging its clout amid the power churn and wants to present itself as a reliable ally for DC amid this new environment. As reports of Russia speeding up the recruitment of mercenaries from Africa emerge, Washington’s decision to tighten security and economic bonds with Kenya likely forms the pragmatic cornerstone of the Biden administration’s strategy to retain a foothold in this dynamic region. The US designation of Kenya as a “major non-Nato ally” during Ruto’s visit sends a strong message. This status would deepen military cooperation, granting preferential access to American defence equipment and training, though not constituting a formal defence pact like that enjoyed by countries across Europe. The move signals Washington’s intent to make Kenya the regional anchor state around which it crafts and executes its broader foreign policy goals in East Africa.

Potential friction points

The cooperation between the United States and Kenya is not devoid of tension and potential hazards for either party. Given Kenya is expected to bear the substantial cost of this new geopolitical development, it may expose it to a rising wave of anti-Western sentiment throughout Africa. Reports of extrajudicial killings, torture, and forced disappearances by Kenya's counterterrorism police have also raised human rights concerns which, if unaddressed, could complicate security cooperation.

The push by the US for Nairobi to become part of the anti-Houthi campaign, despite Houthis not targeting Kenya, will make Kenya a possible target in this proxy war. The Houthis have threatened Somaliland with ballistic missile strikes if Hargeisa allows the UAE to base there. Kenya’s involvement in US-led security initiatives could expand the number of foes interested in targeting it. Kenya’s perilous fiscal position, weighed down by ballooning Chinese debt from Kenyatta’s infrastructure drive, also complicates the extent to which Nairobi aligns itself with the US. China holds 17% of Kenya’s external debt according to 2023 treasury figures, a consideration policymakers in Nairobi will have to take into account if US interests and Chinese interests clash.

However, Kenya's strategic convergence with the US appears poised to overcome these potential sticking points, at least in the medium term. But, as the African saying goes, Kenya risks becoming the “grass” that suffers from a confrontation of big power interests on its land. Navigating this complicated geopolitical context while maintaining its own security and development interests will need savvy diplomacy.