Tuesday 19 November 2024

Abdulrazak Gurnah: writing the Indian Ocean

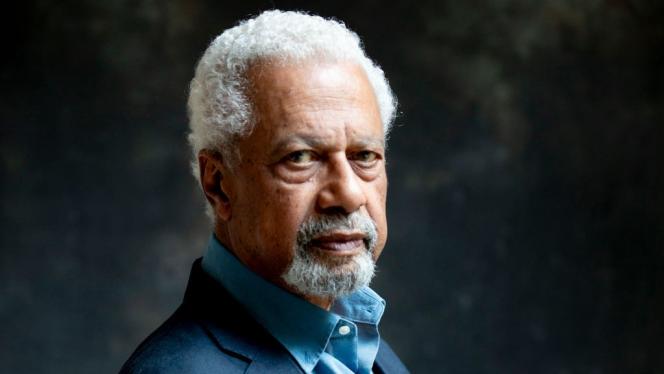

Suhaib Mahmoud reflects on the literature and reception of British-Tanzanian writer Abdulrazak Gurnah, whose literary work tells the stories of Africa’s Indian Ocean region.

The impact of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature took many by surprise. The Nobel Committee often leans into the element of the unexpected, defying the predictions of those speculating on the potential nominees each year. It was Gurnah’s literature though, awarded for “his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fates of the refugees in the gulf between cultures and continents”, that snatched the prize.

However, Gurnah’s win highlights several paradoxes. Much of the global cultural press initially described him as an obscure and relatively unknown writer outside Britain. Yet, this did not prevent him from generating significant attention among journalists and critics following his victory.

African writers hailed the success of an African author receiving the Nobel for the sixth time, celebrating it as a triumph for the “African tribe”, as Wole Soyinka—who won the prize in 1986—once expressed. Gurnah is also the first black writer to be awarded the prize since Toni Morrison in 1993. Meanwhile, the Arab press scrutinised Gurnah’s family lineage, on both his maternal and paternal sides, in an effort to stake their own claim on the basis of his Arab identity while debating the roots of his name. His work hasn’t been widely translated into Arabic though. (I deliberately refrain from using the name "Karnah" invented by some Arab writers).

This article takes Gurnah’s Nobel win as an opportunity to explore some of the most pressing theoretical and critical challenges in interpreting his literature within the framework of African writing. In particular, it examines the limitations in the geographical imagination surrounding various African literary traditions, their critical reception, and the approaches to the histories, spaces, and contexts of these traditions, dating back to the 1960s. Gurnah’s exploration of the Indian Ocean in his novels provides an avenue to address these concerns, especially regarding how critics and scholars engage with African literature, both within Africa and globally.

African literature beyond decolonization

The concept of African literature took shape in the 1960s, closely tied to the liberation struggles during Africa’s national independence movements. This origin story shaped the aims and imaginations of early writers and gave African literature a certain rebellious sensibility. The first conference of young African writers at Makerere University in Uganda in 1962 encouraged African writers to contribute to decolonization. Early trailblazers in African and postcolonial literature attended the summit, including Chinua Achebe, Ezekiel Mphahlele, Lewis Nkosi and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o.

This idea is reflected in the articles by young writers who participated in the conference, which were later published in the magazine Transition. African writers aimed to contribute to dismantling colonialism through their literary work, both in the themes they explored and the positions they adopted. They viewed their role in this endeavour as guides, seeing themselves as educators in much the same way as Africa’s post-independence political elites perceived themselves as teachers of their people. The name Mwalimu, for example, by which Julius Nyerere, Tanzania’s first president, was known, means “teacher.”

Chinua Achebe’s 1965 article “The Novelist as Teacher” further illustrates this idea, asserting that the African novel had an educational mission, and that African novelists held the responsibility of “teaching” decolonization. In the essay, he writes that this task is an “adequate revolution for me to espouse—to help my society regain belief in itself and put away the complexes of the years of denigration and self-abasement.” He said he would be satisfied if all his novels achieved was to remind his people that their history wasn’t “one long night of savagery from which the first Europeans, acting on God’s behalf, delivered them.” Achebe remains one of the most widely taught authors in African literature courses worldwide.

A pressing paradox that emerged from the conference was the acceptance of English as the literary language of Africa, given its practicality. This sparked a heated debate on how to make English an African language, so that it could be treated, as Algerian poet Kateb Yacine put it, as “war booty”, or, as Kamel Daoud suggested, like “the stones from the old houses the colonists left behind”. “The murderer’s words and expressions are my unclaimed goods,” Daoud continued in The Meursault Investigation. Achebe himself made a strong intervention on the subject, asking why English should be singled out for rejection; “what about Arabic? What about Swahili even? Is it then a question of how long the language has been present on African soil? If so, how many years should constitute effective occupation?” he asked.

However, beyond the political and societal struggles that African literature sought to unveil, diagnose, and grapple with, it consistently revolved around responding to the white man. Daoud’s book for example was intended as a companion to Albert Camus’ The Outsider, told from the perspective of the brother of the man Camus’ protagonist kills in his novel. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness similarly inspired V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River and Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North, the latter reversing Conradian journey by depicting a black man travelling to the heart of Europe.

Frantz Fanon criticised this tendency in his book The Wretched of the Earth, arguing that Africans should not regard colonialism as the beginning of their history. He advocated for “manichaeism” in order to destroy the colonial world rather than carve out our places within it. Fanon explains that dislocating the colonial world isn’t enough to undo its harm and logic; imagining a path forward demands nothing less than “demolishing the colonist’s sector, burying it deep within the earth or banishing it from the territory.” It isn’t something we need to respond to, he argues, but something we need to obliterate.

You were either with them or us; white or black; the coloniser or colonised for Fanon. Like many of his theories, his manichaeism also resonated with African writers looking for intellectual resources to help them resist oppressive structures.

Kenyan writer of Indian origin, Abdul R. JanMohamed, was among those influenced by Fanon in his endeavour to outline a socio-political framework for the production of African literature that takes race into account. In his 1983 book Manichean Aesthetics: The Politics of Literature in Colonial Africa, JanMohamed explored the works of six European and African writers, pairing novels with similar themes set in Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya. He argued that colonial writers consistently defended colonial ideology, while African writers sought to dismantle it, resulting in what he termed a negative influence on African writing. He believed that this dialectic was a literary reflection of the socio-political Manichaean relationship between coloniser and colonised.

It is important to note that JanMohamed’s argument was not incidental. He belonged to a generation of east African Asian writers engaged in post-colonial studies, driven by uncertainty about the nationalist rhetoric of post-independence African states. Many of these writers were forced to leave their homelands after independence. Some embraced the ideology of Black consciousness, aligning themselves with the newly independent states and their black citizens, given that, initially, the Manichaean framework offered the liberal hope that both Asians and black Africans could consider themselves indigenous citizens. However, the same Manichaean tendency backfired, leading to attacks on Asians in the post-independence period, such as during the Zanzibar Revolution or the mass expulsion of Asians from Uganda by Idi Amin. This is reflected in the deep pessimism Naipaul’s protagonist, Salim, in A Bend in the River has about the prospects for African independence. In an encounter with Ferdinand, a native, Salim reflects: “Ferdinand could only tell me that the world outside Africa was going down and Africa was rising. When I asked in what way the outside world was going down, he couldn’t say.”

The film Mississippi Masala by Indian director Mira Nair, for example, depicts an Indian family fleeing Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda in the 1970s, amid the climate created by post-independence efforts to construct a race-based identity excluding non-black citizens. This led to the painful uprooting of Africans of Indian, Arab, and Persian descent under the misguided slogan “Africa for Africans”. Nair's film shed light on the plight of Asians in east Africa, a theme also explored in the works of African writers of Asian descent, such as Kenyan M.G. Vassanji’s The Gunny Sack (1989) and South African Ahmed Essop’s The Emperor (1984).

The key point here is that these writers’ representation of Creole cultures challenges the binaries often associated with the dominant, reductionist narrative of African identities championed by some postcolonial African literature. This is an important reason behind the celebration of Tanzanian writer Abdulrazak Gurnah’s recent Nobel Prize win. Born in Zanzibar, an independent archipelago in the Indian Ocean that merged with the mainland upon gaining independence from the British in the 1960s to form Tanzania, Gurnah fled his homeland at a young age due to the hostile climate towards people of diverse origins. Yet he continued to explore it narratively through a complex journey of memory and history. Speaking to the New York Times after his Nobel prize, he said; “The thing that motivated the whole experience of writing for me was this idea of losing your place in the world.”

Gurnah and the writing of the Indian Ocean

Gurnah's literary work is deeply preoccupied with questioning the past and present, exploring the tensions and images within the collective and individual memory of the spaces and regions surrounding the Indian Ocean, with its diverse and shifting periods of turbulent history. The Indian Ocean itself is remarkably a capsule of compressed histories, having, due to its geographical centrality, experienced intense trade and invasions in all directions. Spanning from the southern tip of Africa to Australia, it has been a site of journeys and migrations for thousands of years, continually receiving new cultures, groups, and religions. Although slavery is often understood through an Atlantic lens, the Indian Ocean also witnessed slavery in various forms, whether linked to the Persian Gulf or India, or connected to North America.

Gurnah addresses all this in his literary project. Having left Zanzibar early in life and settled in Britain, his first novel, Memory of Departure, was published by Jonathan Cape in 1987, when he was forty years old, after being rejected by the African Writers Series. His works explore the defeats and psychological and physical agonies of the displaced, reflecting his own experiences of travel and various forms of homelessness. Although the novel is not autobiographical, nor a direct reflection or mirror of the author’s life, it nonetheless clings to reality, absorbing its essence before producing its own version of that reality, whether personal or collective. This is what all ten of Gurnah’s novels achieve. In his first novel, as well as in the second, Pilgrims' Way (1988), themes of migration, departure, modern homelessness, and racism in his new environment emerge strongly. In 1991, he published a shorter work, Dottie, about a girl of mixed origins struggling with life in Britain.

In Gurnah's works, the Indian Ocean evokes a sense of nostalgia as a cosmopolitan space where multiple cultures negotiate and interact with one another, contrasting with the fantasy of a monolithic “Africa”. However, it is also a place marked by historical exploitation, which the writer emphasises by stating: “The feeling of belonging to that particular world of the Indian Ocean, at least the part that I knew of it, which is largely an Islamic world integrated somewhat into Islamic epistemology… But there are also those other things that really connect to more complex matters. It is a history of violence, a history of exploitation, a history of people coming from other places, especially that part of the east African coast that I came from.”

This perspective allows his works to challenge the familiar ways of reading and interpreting post-colonial African literature.

In 1994, Gurnah published his fourth novel, Paradise, a historical novel distinct from its predecessors, addressing European colonialism and its wars. The novel brought him to the attention of readers and critics alike after being shortlisted for the Booker Prize. His 1996 novel, Admiring Silence, reflects on the unsettling and profound silences of the ocean; the narrator returns to Zanzibar to contemplate possible forms of belonging after the harsh experiences of early exile, resorting to silence as a final strategy to protect his identity from racism and prejudice. In his sixth novel, By the Sea (2001), Gurnah once again explores new forms of departure, focusing on the migrations occurring around the Indian Ocean due to the failure of post-independence states to fulfil their promises of welfare. The novel follows the journey and life of Saleh Omar, who arrives in Britain as a refugee.

His subsequent work, Desertion (2005), addresses the vast cultural differences in colonial east Africa, while the theme of the refugee reappears in his 2011 novel The Last Gift, in which the refugee Abbas dies, leaving behind a tape recording that reveals a harsh history previously unknown to his family. The 2017 novel Gravel Heart moves between Zanzibar and Britain, with the narrator reflecting on the separation of his parents. Gurnah’s most recent novel, Afterlives (2020), explores the little-known German occupation of east Africa through the story of Elias and Hamza, whose lives intertwine during the era of German colonial rule—one stolen and the other sold. The German occupation of Africa isn’t a topic which has been treated enough by African novelists.

Thus, Gurnah’s body of work revolves around specific themes summarised by the titles of his novels: memory, departure, the road, the sea, desertion, life, and silence. All of this unfolds within a single space: the Indian Ocean, an area that forms part of an African cosmopolitan heritage yet to be fully explored. Speaking about the Indian Ocean region, Hamid Dabashi said: “Multicultural locations like Zanzibar, Malindi, Mombasa and Sofala carry the traces of this rich history in which Arabic literature, Persian poetry, and Indian philosophies have come to their African provenance.”

Given the distinctiveness of Gurnah's texts, this blend of languages and composite identities makes him an important figure in African literature, compelling us to read his work through an African literary lens. African literature is often depicted as indigenous, where traditions, indigeneity, magic, and the exotic are foundational elements, encouraged by a range of active critical and literary practices in the field. However, what Gurnah’s literature from the Indian Ocean offers is different. He engages in queries history, identity, and memory, and addresses the modern realities of violent migrations and refuge. This aligns with Homi Bhabha’s observation that “migration, the journeys of migrants, and fearful displacement will be cornerstones of global literature in postcolonial societies”.

Gurnah's texts are distinguished by their sensory richness, and his writing evokes a network of diverse cultural sources, from folklore like One Thousand and One Nights to Shakespeare and the Quran.

Issues of reception and classification

Gurnah’s recent Nobel Prize win has been widely celebrated by African writers, with 150 prominent figures signing an open letter expressing their joy at this achievement. However, what has yet to be discussed is Gurnah’s relationship with the system of African literature, encompassing its institutions, publishers, universities, and critical classifications. Typically, west African and south African writers dominate the field of African novels written in English, while literature from the eastern part of the continent is relatively absent. This absence is linked to the formation of the concept of African literature itself. If we exclude James Ngugi (Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o), who participated in the early discussions and conferences that shaped African literature as an institution and discourse, no other significant name from this region is included within this system. North African Arab writers are similarly absent from this framework.

In the case of Gurnah, although he is younger than the founding generation, how does he differ from the dominant pattern of post-colonial writers in African literature today? The Nobel Prize committee highlighted his contribution to post-colonial literature and his uncompromising exploration of the devastating effects of colonialism. His ten novels are set within the context of the Indian Ocean, exploring themes of abandonment, refuge, eclectic cultures, and fragmentation resulting from being “out of place”. This contrasts with the works of African writers from west and south Africa, who led the first impulses of African literature as a system.

As a result, Gurnah found himself, from the outset, thematically outside the mainstream of the developing African literary canon. His themes were not among the central concerns of national African literature as explored by African writers or critics, and his work developed outside the usual networks of production and circulation within this literary landscape.

In short, what I am trying to highlight is that Gurnah’s case illustrates the limitations of the geographical imagination within African literature and its critical reception. Two key points of significance can be noted here. Firstly, Gurnah faced a crisis with the African literary system that developed from the 1960s onwards when the editors of Heinemann's African Writers Series rejected his first novel, Memory of Departure, in 1986 because they struggled to categorise his work as African, British, or diasporic. This was despite the fact that Gurnah had spent two years at a university in Nigeria before returning to Britain for his PhD in 1982.

Secondly, works by east African writers, or those from the Indian Ocean, are often not included within African literature curricula. For example, a survey conducted by researchers Lily Saint and Bhakti Shringarpure in 2020 of 250 professors of African literature worldwide found that, out of 105 respondents, Gurnah's name did not appear in the list of 369 novels mentioned as being taught as part of departmental curricula.

We now see publishers competing to acquire translation rights for his works, and within a month of his win, twenty publishers announced the acquisition of rights to translate his works into 20 new languages, including Arabic. It is also expected that his works will now gain prominence in discussions and teaching within African literature and comparative literature departments.