Thursday 21 November 2024

Our immortal poet: the life and times of Hadrawi

This article chronicles the life of the late Somali poet Hadrawi (1943-2022) from literary, personal, and political angles. His experiences offer valuable insights into Somali history, particularly in tracing the journey of Somali nationalism and the trajectory of the Somali state.

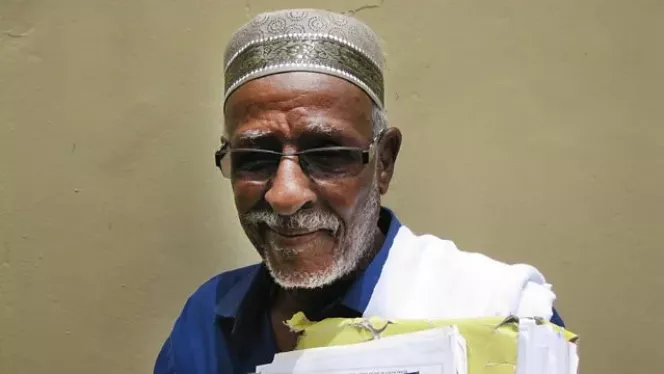

August 19th marks the second anniversary of the passing of Hadrawi, Somalia's most prominent poet. His death prompted a rare wave of unity across Somali social media, transcending the usual political, regional, and generational divides. This anniversary serves as a moment to reflect on the legacy of a man who, at one point in history, managed to unite Somalis both at home and abroad, a task which has grown increasingly complex with the passage of time.

Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame, better known by his nickname Hadraawi, was a poet, lyricist, playwright, translator, university lecturer, and prominent public figure in Somalia. He emerged as a leading voice in Somali poetry during the 1960s and remained a unifying figure in a society where culture often serves as the primary common ground.

Born in 1941 in Burco, a town in what was then the British Protectorate of Somaliland, Hadraawi moved to Aden, Yemen, at the age of ten. At that time, Aden was a cosmopolitan British colony, home to a diverse population from across the Indian Ocean and Red Sea regions, including communities from the Somali coast, Persia, and India. He studied at St. Anthony’s High School in Aden, where in 1966, he wrote his first play, Hadimo (Conspiracy), a drama centred on the brutal assassination of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba. This work established Hadraawi’s early stance as an anti-colonial activist and defender of the oppressed.

In 1967, following the outbreak of the South Yemen Independence War, Hadraawi returned to Somalia along with other cultural figures, such as Said Jama Hussein, who would become icons of modern Somali culture. This generation, known in Somali as Xabbadi Keentay (“Escapees of Gunfire”), left a lasting mark on Somali society.

Somali language and the early independence years

Hadraawi’s return coincided with the seventh year of the establishment of the Somali Republic, which was formed through the union of British Somaliland and Italian Somalia. The newly formed state was determined to reclaim three other regions considered part of the Somali nation: the French Territory of the Afars and Issas (now Djibouti), the Ogaden region in Ethiopia, and the Northern Frontier District in Kenya. This policy, known as Greater Somalia or Pan-Somalism, aimed to unite all Somali-inhabited territories under one flag.

The Somali state drew its legitimacy from the unity of its people, who shared a common language, ethnicity, religion, and culture. Somali nationalists were heavily influenced by a romantic vision of nationalism, believing, like their Arab nationalist counterparts, that language and shared culture were sufficient to create a unified identity among the Somali regions still under colonial rule. As with most nationalist discourses based on supposed unity, linguistic and religious minorities were often marginalised, which was precisely what happened in Somalia.

The pivotal role literature played in shaping the new nation’s identity was quite significant. Somali nationalist literature developed alongside the emergence of the Somali state and its struggles, with many of the writers supporting it inclined towards Marxism. This ideology promoted literature that was committed to the fight against colonialism and exploitation. Writers of this movement began portraying the young nation with ambitious imagery; for example, it was often depicted in romantic nationalist songs as a milk-producing camel, a symbol of prosperity and abundance. This metaphor appears in the songs of Hussein Aw Farah (1928-1998) and Abdullah Sultan “Timo Adde” (1920-1973), who referred to the nation-state as Mandeeq—a term meaning “that which delights the heart”. Their songs were regularly broadcast on national radio, embedding the image of Milky Mandeeq in the popular (and pastoral) imagination, portraying the state as the provider of all wealth.

Amidst this cultural atmosphere, Hadrawi emerged as one of the most prominent romantic poets, creating plays and songs that intertwined love for the land, mother, and beloved. This theme can be found in songs like “Jacayl dhiig ma lagu qoray” (Love Written in Blood) and Baladwayne, which merge his affection for a girl with his love for the town of Beledweyne in central Somalia. The voice of the lover in these songs could simultaneously represent both the girl and the town.

By 1969, the trajectory of state-building across Africa and the Arab world shifted dramatically. In Libya, Sudan, and Somalia, military officers—Muammar Gaddafi, Jaafar Nimeiry, and Siad Barre, respectively—seized power, promising reform and modernisation. In Somalia, the military regime embarked on a nationalist project that prioritised Somali culture, launching extensive literacy campaigns, establishing national academies, and officially recognising Somali as the national language, with the Latin script adopted in 1972. The regime also Somalised education, built national museums and theatres (ironically, Barre's policy of linguistic nationalism coincided with Somalia’s membership in the Arab League).

Artists and writers were key contributors to this cultural revolution, raising public awareness of nationalist ideals. One of Hadrawi’s songs, composed during the official codification of the Somali language, advocated the use of the mother tongue:

“I must be devoted to Somali

develop through Somali

create within Somali

I must be rid of poverty

and give myself for my own mother tongue”

The poet’s paths with the nationalist experience

The experience of Somalia's nationalist military regime closely mirrored similar movements in Africa and the Arab world. The regime focused on modernising the economy, supporting industry, theatre, culture, and education, while also positioning itself as a defender of the nation’s sovereignty through involvement in regional and international disputes. However, as with many regimes of this kind, it eventually slid into authoritarianism.

Consequently, the relatively amicable relationship between the literary elite and the military regime was short-lived. During this period, Hadrawi became one of the most vocal critics of Somali politics, dedicated to exposing oppressive and authoritarian powers, be they military or colonial. Like many intellectuals from the Global South at the time, Hadrawi embraced communism, advocating for the liberation of the Global South from imperialist control. His poetry touched on a range of global struggles, including tributes to Léopold Sédar Senghor, critiques of the United States’ war in Vietnam, calls for the liberation of Palestine, and condemnations of apartheid in South Africa. One of his poems encapsulates his commitment to society as a poet:

The well-made poem has no price,

it’s no jumble of words,

not just drums and empty songs,

nor shaking hips and showing off;

it's not some itch or an insomnia -

it isn't bought for tuppence.

It is that which can't be bought at mart,

that anxiety, those emotions,

it mirrors the people’s needs

and bears their well-being worthily;

it is the warning cry,

the hand that wards off danger,

it never picks one over another,

but points out the correct path;

it is the past's inheritor,

it is always to the point - select from it

the essential flesh and marrow…

Hadrawi significantly advanced Somali poetry, partly due to his experiences in Yemen during the 1960s, where he was exposed to diverse literary genres and artistic forms, including stories, plays, and poetry. This exposure enabled him to challenge traditional structures in Somali poetry and helped foster a new, rebellious generation of poets who drew from a wide array of political and ideological backgrounds.

His poems became emblematic of the era; carrying and driving forward the zeitgeist in Somali art, evolving beyond traditional lyricism to adopt a style more akin to the rhythm of prose. This transformation earned his work unparalleled popularity. Many of his songs were performed by celebrated Somali artists like Mohamed Mooge Liibaan, Halima Khalif Omar (Magool), Mohamed Suleiman Tubeec, and Hassan Aden Samatar.

These performances captivated the public and created a dilemma for the government, which, despite the growing critical tone in Hadrawi’s work, was unable to ban the beloved artist. His works resonated deeply with the people, reflecting their struggles for social justice and opposition to western imperialism and military bureaucracy, further embarrassing the regime.

In 1973, Hadrawi launched a series of poems titled Siinley, which became a manifesto against the authoritarian regime, including a song that mourns the death of Mandeeq, titled Hal la qalay (The Slaughtered Camel). In this work, which narrates the fate of the “she-camel state” under military regime, the poet predominantly employed rebellious rhetoric. This song along with his 1973 play Tawaawac (Prosecution), which also criticised the military government, led to his imprisonment in Qansax Dheere for five years (1973-1978). His works were banned, but he continued to write poetry, which was smuggled to the public and widely circulated. During this time, he wrote some of his most diverse poems, ranging from history to social and global issues, human rights, and philosophical reflections on human life and destiny.

His smuggled poems inspired other poets, such as his companion Mohamed Hashi Dama “Gariye” (1949-2012), to join in the Siinley series, which would become the most significant political poetry series in modern Somali literature.

The military regime intensified its nationalist fervour during the 1970s, focusing on reclaiming lost Somali territories. It supported insurgency efforts in Kenya’s Somali-inhabited region and launched a brutal war in 1977 against Ethiopia, which had recently aligned with the Eastern bloc following Mengistu Haile Mariam's coup against Emperor Haile Selassie, who had been backed by the United States. In a surprising turn of events, the Soviet Union shifted its support from Somalia to Ethiopia, deploying troops from South Yemen and Cuba to aid the Ethiopian regime. The Somali army suffered a devastating defeat, which led to internal divisions and a failed coup attempt by Colonel Abdullah Yusuf and others against Siad Barre. These officers initially fled to neighbouring Kenya and then to Ethiopia, where they formed the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) with the aim of overthrowing Barre's regime.

The poet’s alienation and the states collapse

Hadrawi was released from prison on April 8, 1978, just a day before Abdullah Yusuf’s failed coup attempt. From that point on, Somalia entered a new phase of internal strife, with violent divisions and the formation of armed fronts abroad to overthrow the increasingly tyrannical regime. The country plunged into civil war, with the regime bombing cities with white phosphorus and enlisting mercenaries from South Africa’s apartheid regime to crush its people. Hadrawi was among the intellectuals who decided to fight the regime, joining the Somali National Movement (SNM).

The fight against, and eventual overthrow of, the military regime by opposition fronts, supported by Ethiopia, has ignited—and continues to ignite—fierce debates among Somali elites of all political affiliations. A central question remains: how could we seek assistance from a country with which we had recently fought a war? A nation once regarded as our “existential enemy” and that still “occupies” Somali territories? This question became even more pressing after the opposition fronts failed to present a clear political alternative following the regime’s fall. Aside from the Somali National Movement (SNM), which declared the secession of the northern regions—now Somaliland—and their return to colonial borders, the country descended into civil war, the effects of which continue to plague Somalia today.

Hadrawi’s decision to join the struggle against Siad Barre, and his involvement with the Somali National Movement (SNM), founded in 1982, is now viewed through the lens of 40 years of division among Somalis over that pivotal stance. Today, these divisions persist, particularly on social media—not so much over the validity of the decision to overthrow the regime, but rather over the consequences it has produced.

The debate centres on the meaning of Somali independence; especially after the collapse of the nationalist and expansionist vision that had once formed the basis of post-independence Somali state’s raison d’etre. This debate (or conflict, to be more precise) stems from the failure of Somali elites to resolve the underlying issues with their postcolonial borders through diplomacy and then later through force. When the public lost hope in the realisation of this vision, marginalised groups began contesting Barre’s authoritarian regime.

The five colonial regions have largely made peace within the political systems of their respective national entities: Djibouti gained independence in 1977 and declared that it would not join Greater Somalia; Somaliland established its own state after the war and declared its withdrawal from the union in 1991; and the residents of Kenya’s northeastern province have become well-integrated citizens of the Kenyan state. As for the Somalis of Ethiopia, although they have suffered through the difficult transformations of the Ethiopian state, today they have their own federal region within the current federal Ethiopia. In 2018, the Ogaden National Liberation Front, the last remaining and largest Somali rebel group, even laid down its arms.

In contrast to other Somali regions, elites in Mogadishu appear to have re-embraced ideas that challenge the borders of neighbouring countries, particularly as they increasingly feel under siege. The agreement between Hargeisa and Addis Ababa threatens to formalise Somaliland’s declaration of independence, causing outrage in Mogadishu. This led President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud to refer to Ethiopia's control over the Ogaden region as an occupation. Adam Farah, the deputy chairman of Ethiopia's ruling Prosperity Party—and himself a Somali from the region—described Mohamud's remark as a “surprising statement.” This development comes at a time that the southern region, once the seat of the Somali state, is mired in chaos.

Southern Somalia remains, experiencing internal divisions, with the rhetoric of romantic nationalism still present, as is happening these days in the ongoing dispute surrounding the memorandum of understanding between Somaliland and Ethiopia. The Somali president declared that Ethiopia occupies Somali territories, referring to the Somali region in Ethiopia. To which Ethiopia has responded through its Deputy Chairman of the ruling Prosperity Party, Adam Farah, who hails from that region, calling it a surprising statement.

Returning to Hadrawi, while the announcement of Somaliland’s formation was made by the front with which he had fought, his stance on secession was ambivalent. Whilst he fought with the SNM, his statements afterwards were more circumspect, and he maintained his connections with Somalis across the board likely owed to his great fame. However, what is certain is that the failure of the union resulted from the collapse of the central state, which had been engulfed in wars and internal strife. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that Hadrawi did not retreat into isolation after his return, as many other literary and national elites did by remaining in Somaliland. Instead, he continued to advocate for the dream of a unified Somali nation, remaining steadfastly loyal to that vision. In 2003, Hadrawi embarked on a peace journey across Somalia, which took him as far as Kismayo, a coastal city in the far south, accompanied by fellow poets, writers, and musicians. He repeated this experience in 2006, in the midst of the Ethiopian military invasion of Somalia, reinforcing his commitment to national unity and peace.

In his later years, the poet lost faith in world communism and the ability to continue renewing his poetry. His experience in British exile (1991–1999) was filled with frustrations. He suffered from a kind of discrepancy between what he deeply believed in and its practical futility, as can be seen in his resounding poem Dabahuwan, in which he critiques the forced modernization in the Somali experience and its disastrous consequences for the Somalis. Yet despite these various alienations, Hadrawi never abandoned his commitment to his homeland and his larger nation, which became an obsession that preoccupied him, as he continued to speak of it in a manner that transcended reality.

What makes Hadrawi a unifying figure among Somalis today is his unique poetic style and his uncompromising commitment to Somalis as a whole. His poems speak to all Somalis and cut across their political divisions. Unlike other writers who aligned their creativity with clanism or regionalism, Hadrawi made Somali poetry shine on the global stage. Most foreign journalists call him the Somali Shakespeare. This label is an attempt to simplify things for readers; but it also aims to add value to eastern works by equating them with their European counterparts, which is a flawed assumption that tries to understand one language or culture through the lens of another rather than on its own terms.

Finally, we must ask: what remains today of the dreams that Hadrawi championed for over half a century? It would not be an exaggeration to say that all of them still endure. The Somali nation, as a cultural entity, continues to share a common culture, history, and sentiment, and remains deeply loyal to him and his unique perspective. This is evident from the scenes of unity surrounding him on the anniversary of his passing. However, it is equally clear that Somalis have failed to form a political nation based on citizenship within a single, unified state—a failure underscored by the collapse of the state following the fall of the military regime three decades ago, and the persistent impossibility of restoring it to this day.

Today, culture remains the only point of convergence for Somalis, and they must safeguard the legacy of their immortal poet. They must also work to promote and translate his works for a broader global audience, to which he belongs through his art, literature, and remarkable heritage. After all, didn’t Jorge Luis Borges declare that the heritage of a poet is the heritage of the world?