Thursday 21 November 2024

"Somali intellectuals align themselves with clans, not with the whole": Ali Ahad

Somali scholar and critic Ali Mumim Ahad speaks to Geeska about Somali poetry, the responsibility of Somali intellectuals and Somali history

Ali Mumin Ahad is an accomplished academic scholar with a diverse and impressive background. His academic journey commenced with an undergraduate degree in economics from the esteemed Somali National University in Mogadishu. He furthered his studies by obtaining a master's degree in the Economics of Agricultural and Food Systems at SMEA, a division of the University of the Sacred Heart of Milan.

Subsequently, he earned his PhD in Humanities from La Trobe University in Australia. Currently, Ali holds the esteemed position of Fellow at The University of Melbourne. Having spent a significant portion of his life in Italy, a former colonial power in the country’s south, Ali has left an indelible mark on the field of Somali studies. His extensive body of work includes numerous articles and several books, predominantly focusing on the history and literature of Somalia, along with colonial historiography.

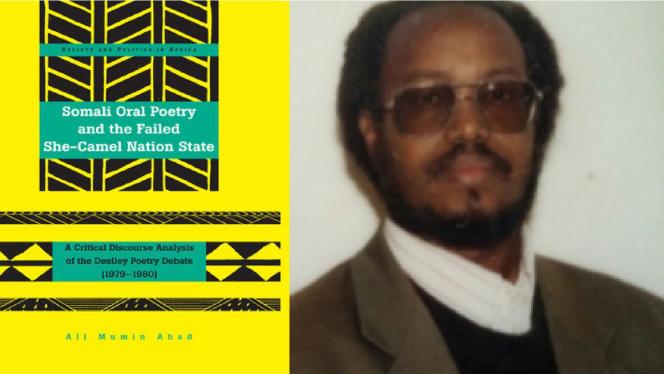

One of Ali Mumin Ahad's notable contributions is the critically acclaimed work titled “Somali Oral Poetry and the Failed-She Camel Nation State: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Deelley Poetry Debate” (1979-1980). Published in 2015 by Peter Lang Academic Publishing in New York, USA, this work stands as a testament to Ali’s profound insights and scholarly prowess. It was a privilege to conduct this interview with Dr. Ali M. Ahad for Geeska, and I extend my gratitude to him for his generous availability.

Ali Mumim Ahad speaks to Geeska about the meaning of home, the ethical responsibilities of the Somali intellectual, the roots of clannism and the early history of Somalia.

Suhaib Mahmoud: To commence, archives serve not only as repositories of a nation's history but also as guardians of our collective memory. Regrettably, we lost this invaluable archive during the Civil War in our generation. As you may concur, archives function as the raw materials of history, comprising the documents that enable us to comprehend the past and explore the depths of the human experience.

I would like to delve into the significance of your essay, "Gurigeenni-Away" (I was truly captivated by its content, although it appears to be an unfinished series). I am interested in understanding its potential impact on younger generations within the diaspora. In your view, how does the dissemination of such knowledge contribute to a more profound understanding of their backgrounds and the pursuit of answers concerning "home" in both its literal and figurative senses? This inquiry is especially pertinent given the unique challenges faced by diasporic generations.

Ali Mumin Ahad: Gurigeenni-Away was the introduction of a series of essays inspired by my daughter, Fatima Ahad, who had suggested a project to introduce the Somali youth in the diaspora to the culture of their parents’ homeland. The series title also shares a reference to a Somali nursery rhyme with a seminar organised with a young Somali postgraduate student (Kaytsen Jama, she is a PhD candidate now). The aim of the essay series is to allow the diasporic Somali youth to, on the one hand, always remember the far away country of their cultural background and, on the other hand, in their search for a country (‘Gurigeenni-Away?’, which could be translated into English, ‘Where is our country?’ and is a play on the English word ‘away’) to view themselves as citizens on equal footing with everybody else in the country they are actually living in. For instance, being born and raised outside Somalia was not, for many of them, an opportunity to develop an awareness of the negative effects of a tribal and clan sense of belonging. Letting the youth understand the root causes of tribal conflict in Somalia was one of the intentions and targets of those essays.

Fatima and Kaytsen were born in Italy and Australia respectively and both raised in Australia. Their very strong will to learn about Somali culture and language in addition to extraordinary organisational and communication skills were fundamental for conducting, in Kaytsen’s case, the seminar, and in Fatima’s the development of the essay series with aims to help the youth develop a critical attitude towards tribal ideology.

In our understanding and belief, educating the youth with a culture of citizenship could represent an alternative to the clan belonging as an individual’s defining identity. For such an identity defined in clan terms is a harbinger of tribal antagonism which is so evident in Somalia today. On the contrary, an identity defined in terms of citizenship can create in the young person a detachment from tribalism, that is, the tribal ideology.

SM: You’ve made your mark not only as a scholar but also as a poet and critic in a society that has earned titles such as the “Nation of Poets” and “Nation of Bards,” as noted by figures such as the Canadian writer and translator, Margaret Laurence. Previously, you wrote an intriguing article titled “Could Poetry Define Nationhood? The Case of Somali Oral Poetry and the Nation” could you talk to us a bit about the links between nationhood and poetry?

AA: Titles like “Nation of Poets” and “Nation of Bards” as noted by Margaret Laurence, I would like to think are not derived from the famous lines of Mussolini’s speech of 1935; lines which are carved on the façade of a monumental building of the Fascist Era in Rome which read; “People (the Italians) of Heroes, Saints, Poets, Artists, Navigators, Colonizers and Transmigrators”. The statement was a vehement protest against the condemnation by the League of Nations of the Italian aggression against Ethiopia in 1935. I think that Margaret Laurence’s notation resonates with those words of Mussolini.

However, it is true that poetry is a fundamental instrument for the transmission of our culture, and it is true that poets represent, within Somali society, the vox populi. A people who were and still are subdivided into clan families, which uphold an ideology (tribalism) that strongly contrasts with the civic identity of a citizen of the state. Tribalism is an ideology that divides a people and condemns a society to perpetual fragmentation, such that even today it is visible and obvious to our eyes. Colonial scholars called it a segmentary society. In such a context, it was unquestionable that the poet’s artistic creation was mostly driven by the need to stand up for and defend his clan or tribal group. That subdivision of Somali society into clans, sub clans and sub-sub clans was formalized in colonial times by colonial anthropologists and is a representation that worked against Somali society as a nation and a state. It is because of the characteristics of Somali poetry in its main orientation that gives way to the question posed in the title of my 2008 article, “Could Poetry define Nationhood? The Case of Somali Oral Poetry and the Nation”.

SM: Later, you delved into the realm of Somali poetry and its connection to nationalism/state/tribalism, notably through your book, “Somali Oral Poetry and the Failed She-Camel Nation State: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Deelley Poetry Debate (1979–1980)”.

Could you share your insights on how oral poetry has influenced social interactions, particularly its impact on the notion of the “she-camel state” as you highlighted in your work? You also referenced the concept of “reer guuraa” dominating the state and introduced the significant term “she-camel state”. Could you elaborate on your intended meaning by using this term?

AA: In pastoral settings, poetry and poets were intrinsically a product of the social interactions between tribal groups. The central object of these interactions were the camels, the main capital and measure of value in that setting. For their possession, wars were waged against neighbouring clans and raids were carried out to take possession of other people’s camels. All this because camels were socially highly valued, their possession represented and symbolised the wealth and importance of the clan as a social group, as well as individuals belonging to the clan. Hence, the symbolic expression of the camel within oral poetry epitomises wealth and valour in the Somali pastoralist society.

In an oral society like Somali society, cultural products circulate with the movement of people across distances and are orally transmitted and shared. During the time where more people moved to non-pastoral areas or within sedentary populations, these cultural products of the pastoralist settings also moved to the new places, and they became part of the shared knowledge. Radio broadcasting plays a unique role in the diffusion of nomadic pastoral culture in the urban environment through songs, imagery and poetry centred on camel herding and the values of nomadic society and lifestyle. Radio Mogadishu and Radio Hargeisa were functioning as places of artistic creativity, entertainment, and information, as well as representation of the country’s cultural policy.

In different times, Somali coastal as well as inland towns witnessed unprecedented urbanisation by people leaving their nomadic pastoralist way of life and choosing an urban way of living. Especially during the colonial era when many young men from the rural pastoralist areas were employed as askaris in the Italian colonial administration.

That first wave of urbanisation by militia reached its peak after the war with Abyssinia and the consequent defeat of the Italian colonial army. Many of the Somali soldiers under the Italian flag returned as war veterans and settled in urban centres. In addition, members of the British army who defeated the Italians in overtaking Italian Somaliland joined the veterans of war under the Italian flag and were employed at different levels in the British Military Administration (B.M.A.) in Mogadishu. As the Italians were defeated in the Second World War, the British who already had the Somaliland Protectorate, also took the former Italian Somaliland under their administration from 1941 to 1949 when the United Nations decided to hand the southern colony back to Italy under a trusteeship administration for 10 years to prepare the country for its independence in 1960.

A second wave of urbanisation of people leaving the pastoralist life and environments for the cities takes place during the Italian Trusteeship Administration in the 1950s. These phenomena of urbanisation transformed the demographic composition of the capital city as well as other minor centres in the former Italian Somaliland. The second wave of urbanisation coincides with the period of formation of the future state bureaucracy as well as that of Somali political institutions. So, at the eve of the Somali independence, an overwhelming component of the urban population were constituted by people who had their cultural background in the nomadic pastoralist environment. The newly urbanised nomadic pastoralists introduced into the towns for the first time a new form for cultural and social relationships, that is, the clan and the kinship system then widely practised in the nomadic setting.

SM: There remains an unfinished question on the boundaries of the nation and the state in the Somali experience, from the Union Republic to the current situation in Somalia and Somaliland. What is your take on that?

AA: Somali independence coincides with what is called the Year of Africa when many former European colonies in Africa acquired their sovereignty from colonial domination, becoming independent states themselves. However, in the case of Somalia there were different colonial powers who were exercising authority over its population in the different regions: France, Ethiopia, the United Kingdom and Italy.

The British colony (British Somaliland Protectorate in the north) and Italian Somaliland extending from north to south, were the first to become independent within a few days of each other, on June 26 and July 1, 1960, respectively. The nationalist party leaders in both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland agreed to become one sole independent state. Soon after independence and the birth of the Somali Republic in 1960, the leaders of the former British Somaliland began to express discontent because of the roles accorded to them in the newly formed institutions. Their expectations were not met.

Even though the people in both former colonies were the same, the different colonial experiences developed different bureaucratic systems, military and institutional structures which were difficult to amalgamate. Furthermore, the languages of the two bureaucratic systems were different and so was the staff’s attitude towards work, as Italian still was the language used in the administration. Later, the Somali government accorded importance to English as the language of work in public offices.

From that time onward, the state bureaucracy gave more and better opportunities to individuals from the northern region (the former British Protectorate) with respect to the mainly Italian educated personnel in the north-east and southern regions. At one point, by the second half of the 1960s, education departments and schools became privileged places occupied by officers and teachers hailing from the north. They were better suited with the new government policies that favoured English instead of Italian in the government departments and ministries. This trend continued until the adoption of an orthography for the Somali language in 1972 and it became the official language of the administration from then on.

SM: To conclude, I want to ask you about the role of the Somali intellectual, you once stated the term intellectual has depreciated in the Somali language and is now used when referring to practically anyone. You said: “In the use I make of the word, I refer only to he or she who feels the responsibility for all, not for a particular group of people. I am thinking, above all, of those who put their ideas clearly in writing; I refer to those who are able to read the ideas of others and respect them.” Do you believe that the Somali intellectuals and scholars have failed to be organic intellectuals as in Gramsci’s terms, who think about all?

AA: Somali intellectuals, like poets of the nomadic society, seem to be more aligned with their respective clans than acting and performing their role as intellectuals, that is, feeling responsibility towards the whole nation. It is this tendency of the Somali intellectuals that makes them organic to the clan they hail from. Not so much as leaders in charge, but only as powerless followers of the clan politician or the traditional leader, a role coined and empowered during the colonial era, the subject of whose influence within the clan the colonial authorities used for the domination of the country and its people.